Wall Street bids a not-so-fond farewell to exchange traded notes

Simply sign up to the Exchange traded funds myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Exchange traded notes, the smaller and often unloved cousins of the bigger and broader $6tn exchange traded fund industry, seem to be dying out — and few lament their passing.

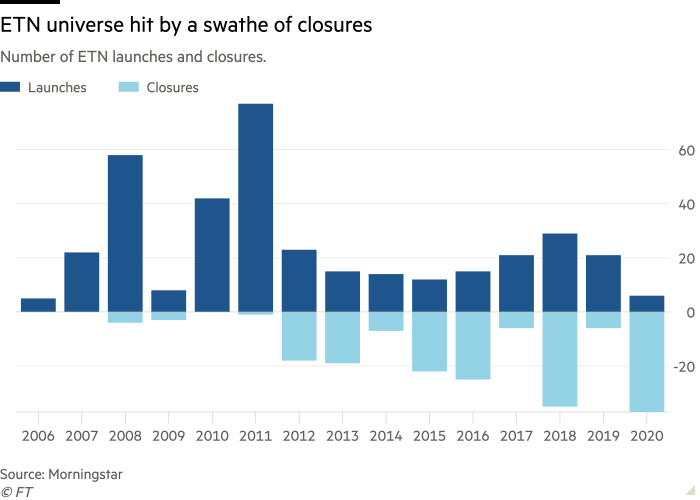

The assets of ETNs peaked at almost $30bn in 2015, following strong growth in the 2000s, but currently stand at just $8.6bn, according to Morningstar data. Analysts say the instruments’ complexity and risky features have made them increasingly unpopular both with investors and some of the banks that sponsor them.

“We’ve seen a lot of [ETN] products in effect orphaned by their parents this year,” said Ben Johnson, head of ETF research at Morningstar. “I don’t think anyone will shed a tear over their demise.”

While the ETF vehicle is a tradable bundle of securities, and subject to much of the same regulation as mutual funds, ETNs are created by Wall Street financial engineers from derivatives, as a way of mimicking the performance of an underlying index. They are in practice IOUs from a sponsoring bank, which promises to deliver the returns of the index in return for a fee. Investors are therefore exposed to the risk that the sponsoring bank fails.

The nomenclature can seem confusing. Although the official umbrella term for both ETFs and ETNs is “exchange traded products,” the dominance of ETFs means that all ETPs — including lesser-known variants such as exchange traded commodities and exchange traded instruments — tend to be referred to as ETFs.

That has long vexed the likes of the largest ETF providers, such as BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street, who fret that many of these niche ETPs can be poorly constructed, riskier than they appear and confusing to many ordinary investors. They also worry that a failure of even a small ETN could tarnish the wider ETF industry.

Their fears have been borne out by instances such as the February 2018 implosion of XIV, a complex ETN sponsored by Credit Suisse and VelocityShares that allowed investors to bet on the US stock market remaining tranquil, through derivatives tied to the level of the Vix volatility index. Credit Suisse killed off XIV in 2018.

Earlier this year the industry’s “Big Three”, as well as Invesco, Charles Schwab and Fidelity, launched an initiative to clarify the categorisation of various ETPs, asking US stock exchanges to carve out ETNs, ETCs and ETIs from a more restrictively defined ETF umbrella.

The main aim is to get leveraged ETPs that use derivatives to juice returns or allow investors to bet on an index falling — so-called “inverse” ones — reclassified as ETIs. Naturally, the smaller companies that specialise in these products object to the initiative, and some analysts said that it might not simplify matters anyway.

Nonetheless, ETNs have also fallen out of favour with some banks that structure them. Credit Suisse, the biggest ETN sponsor, earlier this summer announced that it would delist and suspend nine of its leveraged and inverse ETNs. They were not completely closed, as they are structured as debt securities with a finite lifespan, but would from July 12 trade away from mainstream stock exchanges on an over-the-counter basis.

Among the ETNs that have now moved into financial purgatory was TVIX, a popular trading product that aimed to deliver twice the daily return of the Vix index.

Credit Suisse declined to comment on why it delisted the ETNs. At the time it said the decision was made “to better align its product suite with its broader strategic growth plan”.

Inside ETFs

The FT has teamed up with ETF specialist TrackInsight to bring you independent and reliable data alongside our essential news and analysis of everything from market trends and new issues, to risk management and advice on constructing your portfolio. Find out more here

Just six ETNs have been launched this year, according to Morningstar, while 37 have been closed. As a result, the total available range of ETNs has dropped to 185, the lowest since 2010.

Some still believe that the products’ advantages — such as their versatility, and their tax-efficiency — can overcome their downsides. “The ETF is a superb product, as you don’t have any exposure to the issuer. But that doesn’t mean that ETNs will disappear,” said Fabien Labouret, global head of equities structuring at Barclays.

Yet many in the industry would be happy to see the product disappear. “ETNs are flawed; I would expect the number to shrink even further in the future,” wrote Dan Weiskopf, a portfolio manager at Toroso Asset Management, an ETF specialist, in a recent report. The title? “ETNs Should Go Away.”

A short history of ETNs

Although much smaller than the universe of ETFs — both in size and number — ETNs have a long history and play an important part in the history of the evolution of index funds.

The first formal ETNs were launched in 2006, but their lineage arguably traces back to Morgan Stanley’s glamorously named Opals, or “optimised portfolios as listed securities”. Opals were first launched in 1993 — shortly after the birth of State Street’s first pioneering ETF — and were tradable instruments designed to match the return of international stock market indices constructed in a joint venture with Capital Group.

That joint venture eventually morphed into MSCI, one of the world’s biggest index providers, and Opals later became the inspiration for what would ultimately become iShares, BlackRock’s industry-leading $1.9tn ETF business. Nonetheless, many of the leading index fund providers would be happy to see ETNs go the way of the dodo.

Comments