US investors demand data in fight against racial discrimination

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

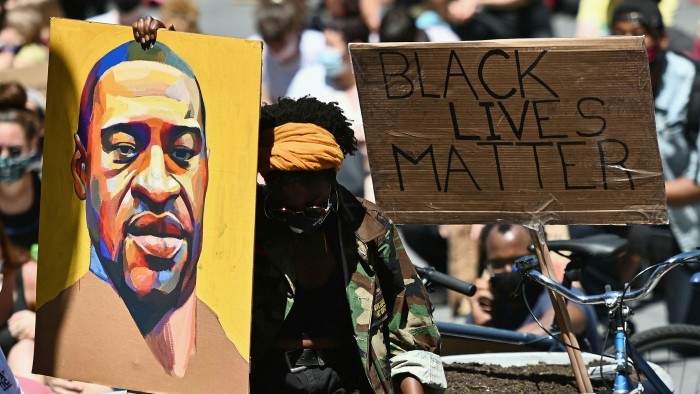

The police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis in May provoked weeks of protests about racial injustice around the world and electrified the political landscape in the US.

The outcry, along with the disproportionate suffering of people of colour in the coronavirus pandemic, has refocused attention on how the US investment sector has failed to challenge systemic racial inequality. This in turn has highlighted how some in the industry are looking for ways to tackle the problem.

Leading bankers have been among dozens of chief executives of blue-chip US businesses who have vowed to address inequalities in their companies.

Larry Fink, chief executive of BlackRock, last month promised concrete action over his company’s admitted shortcomings in racial diversity. The world’s biggest asset manager committed itself to increasing its number of black employees by 30 per cent over the next four years.

Meanwhile a range of businesses including Goldman Sachs, Amazon and Nike have signalled their support for action by donating millions of dollars to anti-racism groups.

These gesture have helped to build momentum among US investors who had already begun engaging with companies to push for improvements tackling underrepresentation on boards and discrimination across the workforce.

Liqian Ma, head of impact investing research at Cambridge Associates, which advises large institutions, says that more endowment funds and foundations are turning their focus to the problem.

“The primary lens that we are viewing this [through] is: it’s the right thing to do,” says Mr Ma. “But it’s also an economic opportunity because there are underserved communities that are held back by barriers to education, healthcare access or clean water and air quality.”

Yet responsible investors attempting to exert a positive influence face a difficult task. Shaping investment portfolios to achieve racial justice “is incredibly difficult, primarily because of the lack of data”, says Mona Shah, director at Stonehage Fleming, a family office.

Simply gauging something as basic as board diversity can be hard.

“We had to look through 150 companies, and we would literally go photograph by photograph looking at the names and Googling the names, because hardly any of the companies will self-disclose,” says Sudhir Roc-Sennett, head of ESG at Vontobel Quality Growth, part of the Swiss investment bank’s asset management division.

Ms Shah believes that new across-the-board obligations, akin to the UK’s requirements for organisations to reveal gender pay gap data, will be necessary to force meaningful disclosure of US corporate performance on racial balance and remuneration.

But some large shareholders are trying to compel companies to provide diversity data of their own volition. The New York City pension fund earlier this month put out a call for companies that made public declarations of support for the Black Lives Matter movement to do a better job of disclosing their diversity data.

“It is not enough to condemn racism in words,” said Scott Stringer, New York City’s comptroller who controls public spending for the city. “This information is crucial for shareowners to better understand diversity and workforce practices and identify areas for growth.”

Public statements in support of racial justice may be good for public relations but are no guarantee that a company is dedicated to making real change, says Kristin Hull, chief executive Nia Impact Capital, an Oakland, California-based investment adviser.

The same goes for responses such as hiring diversity officers or donating money to a civil-rights group. “Having a chief diversity officer is awesome. But if it’s just a name only, that’s not what we need,” Ms Hull says. “What are their budgets? Do they actually have any staff? Are they empowered to get anything done?”

Despite concerns over the paucity and quality of information, some investors and advisers are attempting to apply those tools that are already available to filter out companies which perform poorly on tackling racial disadvantage, while committing to those which do better.

Two years ago, data provider Morningstar added its Minority Empowerment Index to a range of indices designed to appeal to investors with environmental, social and governance (ESG) mandates.

It is designed to provide exposure to US companies “that have embedded strong racial and ethnic diversification policies into their corporate culture” and that deliver equal opportunities to employees “irrespective of their race or nationality”.

Microsoft, Citigroup, Coca-Cola and Intel lead the index’s “minority empowerment score”, which is weighted by quality of board representation, anti-discrimination and diversity policies, and supplier standards.

Another initiative has been taken by Rachel Robasciotti, a self-described “young, queer woman of colour”, who has headed up her own wealth management company focused on investing for social justice since 2004.

For years, Ms Robasciotti has maintained a divestment list of companies involved in industries such as private prisons, immigrant detention and for-profit colleges. Last month, as the Black Lives Matter movement surged around the globe, she decided to make the list public.

If investors want to change the system, they need to stop investing in companies that “exacerbate racial inequities”, Ms Robasciotti says. But she recognises that divestment campaigns can only work with large-scale participation, as happened with campaigns against multinationals that operated in Apartheid-era South Africa.

Ethic, a fintech company that offers customised ESG portfolios, supplies Ms Robasciotti with data from its platform, allowing retail investors to effectively screen out companies at odds with their ethical stances when acting through their own financial advisor or wealth manager. Other investment fintech companies such as OpenInvest provide similar options to investors that want to avoid exposure to companies that do not align with their values.

“If we make that change only in our own portfolio we really aren’t making systemic change,” Ms Robasciotti says. “What it’s really going to take to break the back of these racially unjust systems is for investors to work together in solidarity to have a significant impact on share prices.”

This article has been amended to clarify the relationship between Ethic and Robasciotti & Philipson

Comments