How to take the long-term view in a short-term world

Simply sign up to the ESG investing myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Until recently, the chief claim to fame of the small French town of Florange was as the seat of Lothair II, the Saxon king of Lorraine who fell out with the Pope after he tried to leave his wife for his mistress. But in 2014 its name entered the capital markets lexicon when it appeared in legislation that requires French companies to give double voting rights to investors who hold their shares for two years or more.

The Florange law was named after the industrial community that was at the centre of a bitter row several years after the hostile €26.9bn takeover of Arcelor by Mittal Steel. The company tried to shut down the town’s two blast furnaces — until a French minister accused it of “blackmail” and “lies” and threatened nationalisation.

The incident was an early sign of unease over the short-termism that many companies, investors and policymakers say has undermined progress towards more sustainable business practices.

A short list of long-term strategies

The rise of ESG investing is making more money managers focus on sustainable returns

The emergence of climate-focused shareholders is adding a long-term twist on investor activism

Moving early to anticipate far-off threats to existing business models can turn them into opportunities

Communicating an explicit long-term plan can be critical for getting shareholders onboard

Some companies are rethinking their governance to create separate short- and long-term roles

Tying part of executives’ pay to sustainability targets is becoming increasingly common

Cumulative earnings reporting could shift analysts’ obsessive focus on the next quarter’s results

Seven years on, a host of other responses has emerged around the world, from the launch of the Long-Term Stock Exchange in San Francisco to the ditching of quarterly earnings reports, most famously by Paul Polman when he was chief executive of Unilever.

In this outcry against short-termism, big investors have had the loudest voices.

In 2018, the billionaire investor Warren Buffett joined Jamie Dimon of JPMorgan Chase to lament the “unhealthy focus on short-term profits” that stems from three-monthly earnings guidance.

And the biggest of them all, BlackRock (now with $8.68tn in assets under management) has a CEO, Larry Fink, who frequently complains that companies are too focused on quarterly results.

By early 2020, short-termism was being attacked by everyone from executives at Davos to environmentalists at not-for-profit groups such as the World Wide Fund for Nature.

Their frustration is unsurprising given the evidence of how bad it is for business. In 2020, for example, the CFA Institute, the association for investment management professionals, estimated the cost of short-termism to S&P 500 companies at $79bn a year in forgone earnings. Three years earlier the McKinsey Global Institute found that companies which took a long-term approach had 47 per cent stronger cumulative revenue growth, with less volatility, than other groups. Yet 70 per cent of executives surveyed by McKinsey last year believed that their CEOs would sacrifice long-term growth for short-term financial objectives.

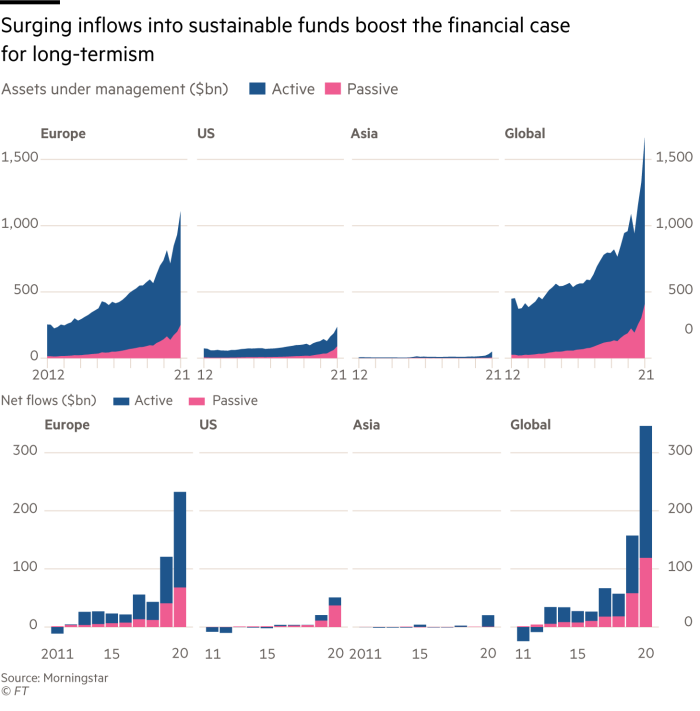

Today the short-term approach to business and investment is also blamed for hampering ESG investing: the environmental, social and governance strategy, which, studies say, drives stronger long-term returns. Last year Morningstar found that funds with higher ESG ratings outperformed their benchmark indices more frequently than those exposed to greater ESG risk. Meanwhile, inflows into ESG investments have risen so sharply that in February 2020 the Financial Times ran an article with the headline: ‘Monstrous’ run for responsible stocks stokes fears of a bubble.

A month after that, the world was turned on its head. With countries locking down their citizens, capital markets nosediving and dire predictions of the economic fallout, the Covid-19 pandemic had CEOs wondering if their companies would make it to the next month. In this moment of acute short-term pressure, the question many asked was whether the foundations of the longer-term, sustainable approach were about to crumble.

The perils of living in the moment

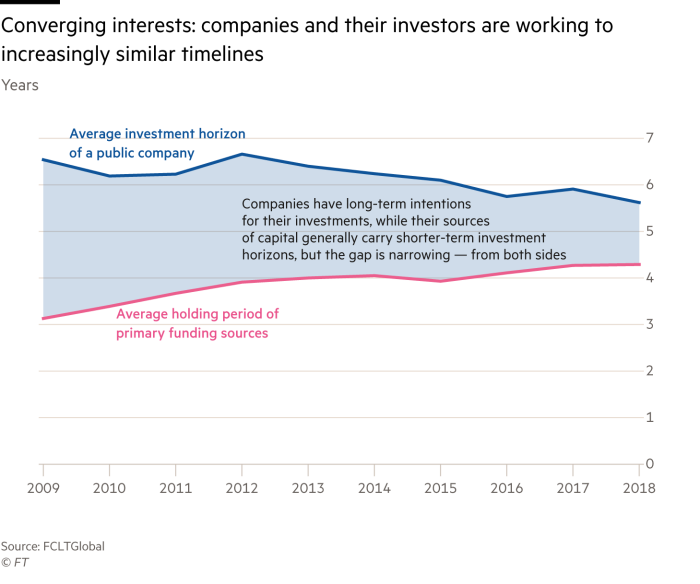

Sarah Williamson likens the persistence of short-termism in business and investment, despite evidence of its costs, to car dealers who offer a discount simply because the end of the year is approaching. “It is pervasive,” says Williamson, CEO of Boston think-tank FCLTGlobal, which champions long-term investing. “People try to hit quotas and they will cut corners to do it.”

Faced with the threats to profits caused by the Covid crisis, the temptation has been to cut much more than corners. Early in the pandemic, this instinct seemed to threaten what had been a growing commitment to sustainable approaches. Just months after 181 US CEOs belonging to the Business Roundtable had pledged to run their companies for the benefit of all stakeholders, including employees, several of them had to make deep cuts in headcount to weather the storm (though some cut their own salaries too).

Of course, short-termism existed long before the pandemic, and laying blame for it on any one player in capitalism’s ecosystem is tough. When we asked FT Moral Money readers whether business was too focused on the short-term, the response was an overwhelming “yes”. But there was less agreement when asked for the reasons. Respondents pointed to everything from executive compensation to an “obsession with quarterly earnings and reporting to appease shareholders”.

Matt Orsagh, a governance expert who is director of capital markets policy at the CFA Institute, encountered this phenomenon while researching Breaking the Short-Term Cycle, the institute’s 2006 report. The team asked finance professionals what drove short-termism. “We got them all round the table and fingers were pointed,” he recalls. “‘It’s the sell side; it’s the buy side; it’s hedge funds; it’s compensation; it’s the earnings guys’ practices.’ We found that everyone was right in that we all played a role.”

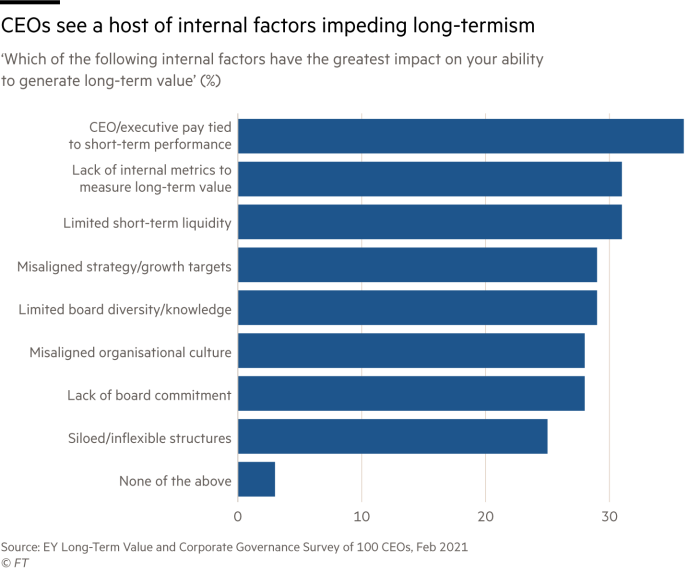

For Judy Samuelson, who founded the Aspen Institute’s business and society programme, one of the biggest culprits is the shareholder primacy mantra, which has been drilled into investors and corporate executives by business schools and the media since Milton Friedman’s 1970s heyday. “It’s the noise they’re constantly hearing,” says Samuelson, author of The Six New Rules of Business: Creating Real Value in a Changing World. The design of executive pay packages amplifies this noise, she says. She also believes that most executives want to do the best for both their company and society but their financial rewards work against this. “They are not unaffected personally by the design of pay,” she observes.

Many investors agree with this. In fact, seeing executive pay tied to short-term share-price moves has become a red flag for some. “Where we tend to be less supportive of executive compensation proposals is when they are single-metric driven, only looking at share price and not considering performance more in the round,” says Sandy Boss, global head of investment stewardship at BlackRock.

Myths persist that maximising shareholder value, including giving priority to short-term gains, is part of a board of directors’ fiduciary duty. Colin Mayer of the Saïd Business School at Oxford university stresses that such falsehoods must be put to rest. “The law not only allows directors to pursue the success of the company for the long-term,” he says, “but in the case of the UK, it requires directors to take into account the impact of the long- as well as the short-term.”

Orsagh sees something even more fundamental at work in the reluctance to think long-term: human nature. Short-termism is so ingrained, he argues, that finding a single easy answer is tough. “Whether it is politics or finance or daily life, short-termism is something everyone struggles with.”

The conversation starts to shift

When wildfires swept through California last year, they not only highlighted the real cost to business of a warming planet, they hammered home the fact that being in the middle of one crisis does not exclude others. For companies espousing long-termism, climate risks have long been part of the discussion. But the pandemic and 2020’s racial-justice protests added the need to promote diversity, health and fair working conditions to the list that is driving companies towards a more strategic approach. “We’ve had a huge wake-up call that employees want something different,” says Samuelson.

One leader who welcomes the new pressures is Claus Aagaard, CFO of Mars, which with Saïd Business School launched the Economics of Mutuality, now an independent think-tank that helps companies to embed sustainable strategies. “The good news is it comes more and more naturally,” he says. “The data is clear in terms of what needs to get done, it is what the talent wanting to join corporations like ours wants to see and it is increasingly clear what consumers want to see.”

However, the push for companies to extend their horizons is coming not only from employees and consumers. In the investment community, money is talking. By 2018, ESG funds represented $11.6tn in assets under management in the US alone, 44 per cent above 2016’s figure of $8.1tn, according to the Forum for Responsible and Sustainable Investment.

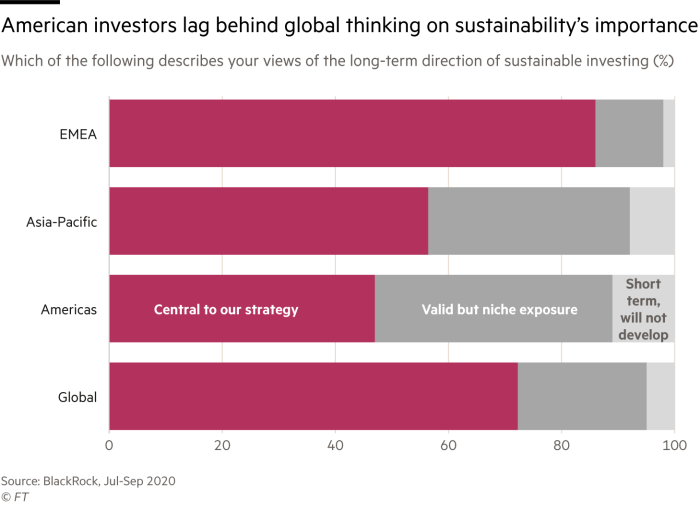

Money managers have also turned up the heat on short-termism. In his 2021 letter to CEOs, BlackRock’s Larry Fink called for companies to demonstrate how their plans to cut carbon emissions and increase workforce diversity will fit into their long-term strategies. Meanwhile, three of the world’s largest asset owners teamed up to send a polite but firm warning to companies and money managers.

In March 2020, Japan’s $1.6tn Government Pension Investment Fund, the $282bn California State Teachers’ Retirement System and the UK’s USS Investment Management (which manages £67bn to provide higher education staff pensions) said they were committed to companies that “create value for us over the long-term”. Asset managers focusing on short-term financial measures at the expense of longer-term sustainability-related risks and opportunities were “not attractive partners for us”. The statement did not specify the consequences for partners deemed unattractive but the message was clear: they would no longer tolerate myopic behaviour.

Activist investors such as corporate raider Carl Icahn have often been blamed for boards’ obsession with the short-term. In recent years, however, a new breed has appeared: the climate activist. Among them is Mark van Baal, founder of Dutch shareholder group Follow This, which pushed Royal Dutch Shell to make a more ambitious commitment to reduce its carbon emissions. Another is Climate Action 100+, an alliance of investors with a combined $52tn in assets under management, which presses companies to cut emissions, strengthen governance and enhance climate-related financial disclosures.

Even mainstream investors that do not identify as activists now ask new questions, says Wendy Cromwell, director of sustainable investment at Wellington Management.

“We’ve done over 18,000 company meetings this year, which is well above our normal run rate, and one of the reasons is that investors are really interested in understanding how companies cope with crises,” she says. “Instead of questions about whether you’re going to beat or miss a quarter, you hear investors asking how has the crisis informed strategic planning or what opportunities might arise after it has passed — things that are more strategic and long-term.”

Tangible evidence of the effect of a warming climate on economies and individual companies has prompted discussion among business and investment executives about long-termism and, by extension, sustainability. FT Moral Money readers have noticed the shift. “The evolving materiality of issues like climate change is such that leading businesses are beginning to factor these existential-threat issues into action now,” observed one. “Are they doing enough? Not yet but there appears to be an increasing realisation that radical action is needed, and it is in the interest of business to lead on this.”

The prospect of more climate legislation undoubtedly plays into this. China, South Korea and Japan are among those to have pledged to become carbon-neutral economies, as has the EU with its proposed European Green Deal. In the US, the Biden administration has stressed its intention to take climate action seriously, and this will include rejoining the Paris Agreement.

So while many wondered whether the pandemic would result in business and the capital markets taking their eye off the ball with respect to long-termism, a number of forces — including the Covid crisis itself — seems to be driving the opposite response. “The fact that we are in the midst of a pandemic makes us all realise there are long-term systemic issues that can have short-term impacts,” says Cromwell.

A tale of two transformations

While companies may understand the need for a longer-term approach, how should they turn that insight into action? One critical approach is to be sure to adapt in anticipation of future threats. Two proponents of this are DSM, the Dutch nutrition group, and Umicore, the Belgian materials technology group. Seeing that environmental pressure could make their businesses unsustainable in the long-term, both have moved away in recent years from commodity operations with heavy environmental footprints to become nimble enterprises focused on science, technology and innovation.

It was not an easy transition for either company. For DSM, whose name originally stood for Dutch State Mines, it meant substantial divestments and acquisitions. In 2002 it sold its petrochemical business. Then it acquired Roche Vitamins and Fine Chemicals, which laid the foundation for the move into nutrition.

Moral Money Forum

“What was interesting was to see the reflection around where to invest the proceeds of exit and the decision to reposition the company to something that a lot of people didn’t know much about,” says Geraldine Matchett, who is DSM’s co-CEO and CFO. “The ability to see that as the next big opportunity and move into it was very courageous and daring.”

For Umicore, the move out of mining and into materials and services for clean vehicles and recycling took a leap of faith — as well as a heavy investment in technology. “What’s behind our transformation is the acknowledgment that we don’t know what’s going to happen,” says Marc Grynberg, Umicore’s CEO. “So we need to be best prepared to seize new opportunities.”

This kind of transformation also requires an ability to hold your nerve, particularly since companies are not always rewarded by investors for every step, and can be punished for the pace at which innovation translates into returns. One way this is expressed is through the longevity of holdings. While a small number of Umicore’s shareholders are in the stock for the long-term, says Grynberg, the turnover of shares is equivalent to the company changing hands in the space of less than a year. “We are rewarded constantly by shareholders with long-term horizons,” says Grynberg, “while for a certain breed of investor, it is never fast enough.”

DSM has had to be resolute in the face of disapproval. “A lot of what we’ve done . . . we did despite market dynamics rather than helped by market dynamics,” says Matchett. She cites DSM’s 2010 decision to link half of its management board bonuses to environmental and social targets, which some investors said was a distraction from the pursuit of shareholder value. Matchett argues that such moves do in fact underpin value creation. “It doesn’t mean you’re going to do crazy stuff,” she says. “It just means you’re taking into account a broader set of factors, which makes you stronger for the long-term.”

Grynberg is unruffled by the fact that only a handful of Umicore stockholders share its long-term horizons. “I’ve always run the company in a relatively conservative manner from a financial point of view so we can perpetuate investment and research programmes regardless of short-term fluctuations in the economy,” he says. “That’s what it takes to counter short-term temptations.”

Putting words into action

Some companies have decided to be explicit in how they demonstrate their long-termism credentials to investors. In late 2020, for example, Borg Warner, a Michigan producer of automotive parts that make vehicle engines cleaner, outlined to shareholders its strategy to adapt to a low-carbon economy. It was not a traditional report on investment return or a presentation of ESG performance. The company gave the presentation a simple title: The Next Decade+.

“For us it was important to convey the message to investors that we are running this company for the long-term,” says Frédéric Lissalde, the CEO. Long-termism, he says, is inseparable from ESG considerations: “It is the long-term thinking that leads to the obvious sustainability levers that we’ve had in the past but that are being formalised and streamlined.”

It is one thing to create presentations but another to ensure they guide all elements of a company’s operations. The mission statement of Enron, the US energy group hit by a corruption scandal in 2001, contained words such as “integrity” and “excellence”. Even when corporate leaders are genuinely committed to long-term investments, they encounter forces that push for immediate results, despite the chance that those investments may deliver significant returns in time. “Think about the [Covid] vaccines that have come to market so fast,” says FCLTGlobal’s Williamson. “The reason they were able to come to market quickly was because those companies had invested in this for years prior.”

At Borg Warner, Lissalde attributes the ability to make long-term investments to the decentralised structure of his organisation. Leaving six presidents to worry about shorter-term activities, he explains, means he and his strategy board can concentrate on long-term goals. “It’s like an orchestra: everyone has their part,” he says. “Some people are absolutely focused on delivering the present. Some are in products where it’s tough to have a long-term focus, and some are here to deliver top margins and cash flow so others can position the company for the future.”

Borg Warner is not alone in viewing governance and organisational structure as being key to a long-term approach that underpins sustainable growth. At Novozymes, the Danish biotech company, the board governs sustainability, while in 2020 a new corporate sustainability committee was created that reports to the executive leadership and is responsible for integrating sustainability into business and innovation strategies.

Novozymes has tied one-fifth of executives’ long-term incentives to sustainability goals and many FT Moral Money readers express a hope that such pay strategies will become more common. So far, they remain the exception. A study by the Conference Board, an international think-tank, found in 2020 that just 604 companies in the Russell 3000 index tied compensation to any kind of ESG target.

The challenge is that linking remuneration to sustainability targets dictates that you have to define what is meant by success. Companies and investors can be forgiven for being perplexed by what many say is an “alphabet soup” of measurements and methodologies.

For years, remuneration committees’ yardstick of choice has been simple: quarterly earnings guidance. That has come at a cost, says Williamson. “If an executive or company says they’re going to make $1.27 to $1.30 [a share] next quarter, they feel an obligation to make that number. What you see time and again is that, if they’re not going to make it, they cut the things that are easy — usually people or R&D.”

She would like to see regulators encourage what she calls “cumulative reporting” in which each quarter would build on the next (three months, six months, nine months and then the full year), which would leave in place the transparency of regular reporting while avoiding the quarter-to-quarter comparisons that drive short-term behaviour.

The change is subtle, she admits, “but a lot of this is about the feedback cycle to the management team”.

Conclusion

In assessing the state of short-termism versus long-termism, there is no shortage of criticism aimed at the former, including from those at capitalism’s coalface. One FT Moral Money reader, Katherine Venice of Public Advocates for Optimizing Capitalism & Economic Justice, links the effects of short-termism — cuts to jobs, wages and benefits that are justified as “rationalisation” or “efficiency” — as driving inequality. “As a former institutional investment manager with three global investment management firms, I have worked inside this very system,” Venice writes. “No one admits this, yet it is so glaringly obvious.”

Even so — and despite pandemic pressures — cautious optimism is growing among investors and corporate leaders that longer-term philosophies are taking root. Compelling financial returns, pressure from investors and asset owners and disdain for quarterly guidance have combined to encourage long-term behaviour. Moreover, the consensus is that this is not only good for the bottom line but it also benefits people and the planet.

“I see the conversations as having shifted pretty significantly,” says Wellington Management’s Cromwell. “And we will watch to ensure that it is enduring and we don't revert to previous behaviours.”

Before putting on rose-tinted glasses, it is worth remembering just how entrenched those behaviours are. With the average stock now held for a matter of months, compared with the 1960s when holdings were measured in years, reversing the tide of short-termism seen in recent decades will take a sustained effort.

There are no silver bullets. To shift business and capital markets in the right direction will require resistance against a host of short-term pressures. However, with the financial case looking clearer, this is a moment for companies and investors to move past the finger-pointing and to support each other in making long-term approaches the default rather than the exception.

Comments