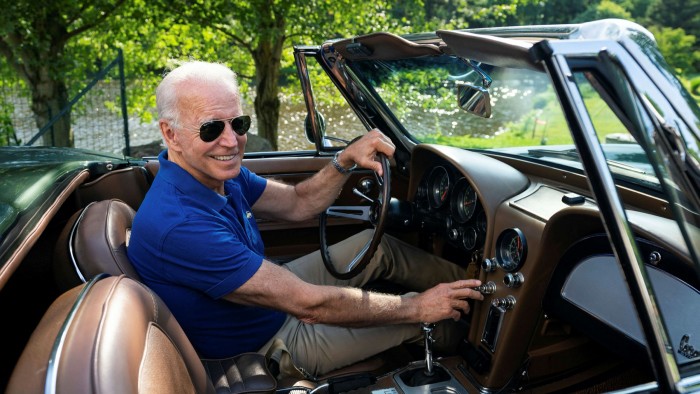

Oil traders should pay attention to Biden’s little green Corvette

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Joe Biden wants to be the greenest president in US history. He also owns a gas-guzzling 1967 Corvette Stingray and is quite happy for everyone to know about it.

The two facts might seem incongruous. But for oil traders hoping to understand what a Biden presidency might mean for the market, the subtle signalling of the Corvette campaign video is worth understanding.

It is, frankly, a beautiful car, a gift from his father for his first wedding. It is also a relic of the pre-Arab oil embargo days of the 1970s, when auto manufacturers did not need to pay much heed to fuel efficiency.

However, the aim of featuring the Goodwood green convertible is to frame Biden’s environmental plan not as some hair-shirted anti-car screed, but as a chance to remake the US automobile industry for the coming decades.

“This is an iconic industry . . . I believe we can own the 21st-century market again by moving to electric vehicles,” Mr Biden says in the clip.

It is his version of “Make America Great Again”, wrapping his green message in the nostalgia of a car-obsessed culture.

His aims are worth taking seriously. The latest poll numbers suggest Mr Biden is on course for a comfortable victory in November, winning 298 electoral college votes to President Donald Trump’s 119, if the election were held today.

Moreover, the US remains the world’s largest oil consumer, even as China has overtaken it on crude oil imports. That gives America an outsized role in the future of the oil market.

While other developed economies have largely seen oil demand decline, a growing population and the popularity of sports utility vehicles has kept US oil consumption stubbornly high.

Petrol consumption alone accounted for 9.3m barrels a day of US oil demand last year, almost 10 per cent of the world’s total, according to the Energy Information Administration.

So any moves by Mr Biden to encourage the electrification of US cars could drive a significant shift.

But to really break the stranglehold of petrol cars on the US psyche, Mr Biden understands the need to occupy the same space as Elon Musk.

Whatever you might think of the Tesla founder, there is little doubt his legacy will be making electric cars desirable. No one views a car with a “ludicrous mode”, which amps up a Tesla’s 0-60 performance, as an assault on fun or freedom.

The traditional US car industry is aware it risks being left behind by European and Asian manufacturers if it neglects the electric market. Tesla has already become the most valuable carmaker by market capitalisation. Ford is preparing to release an all-electric Mustang, one of the most iconic of US muscle cars.

A shift in the US car landscape, and with it the trajectory for oil demand, may be closer than you think.

Throw in Mr Biden’s pledge to cut US emissions to “net zero” by 2050 and fuels such as diesel, used for heating and industry, will also see consumption crimped in time.

For US oil production, there should be little in the former vice-president’s proposals to frighten the better-run companies in the shale patch. While increased regulation around methane emissions and restrictions on new drilling on public lands (which account for a small percentage of the US total) are likely, there is no plan to “ban” fracking, despite some of the more outlandish statements in the Democratic primaries.

US oil production has been hit by the collapse in prices caused by the coronavirus pandemic, but its trajectory will primarily be set by economics rather than politics.

Internationally, the most enduring change would come from the US rejoining the Paris Climate Agreement. Having the world’s biggest economy back on board would not be a panacea for the climate crisis, but it would remove a major brake on progress towards lowering global emissions.

A more obvious shift for the oil market would be the US approach to Iran. A revival of the Obama-era nuclear deal, which is still backed by European powers, would free up more Iranian crude for international markets.

Those barrels would help plug any supply gaps that could emerge later this decade due to an industry-wide drop in investment before peak demand arrives.

US relations with Saudi Arabia could be strained, given that Riyadh has thrown its full weight behind President Trump, but are unlikely to completely unravel. Saudi Arabia may be tempted to pivot towards China, but it may find Beijing, which is increasingly thirsty for oil, even less fond of high prices than the US.

If Mr Biden does win in November, however, it is back home in the US where the most striking changes should be expected. That little green Corvette should be seen as a statement of intent, not a throwback.

Follow on Twitter @oilsheppard

Comments