Beijing’s endgame: football with Chinese characteristics

Simply sign up to the Chinese politics & policy myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

The crowded Billy Wright pub in Wolverhampton, a working-class city in Britain’s West Midlands, is an unlikely jumping off point for President Xi Jinping’s global mission to boost China’s influence.

Yet, as Kevin James drinks with fellow Wolverhampton Wanderers fans in the pub close to the football club’s Molineux ground, he pays tribute to the Chinese conglomerate that bought the team in July 2016. It has pumped in tens of millions of pounds, bought foreign players, cut ticket prices and catapulted the club, which last won a major trophy in 1980, to the top of the second tier of English football.

Fosun’s £45m ($58m) purchase of Wolves forms part of a wider spending spree in response to Mr Xi’s call for a football revolution, with Chinese tycoons investing more than $2.5bn over the past three years in 20 European clubs from giants like Manchester City and AC Milan to smaller outfits such as FC Sochaux, in France, and England’s Northampton Town.

Four of the top teams in the West Midlands — Aston Villa, Birmingham City, Wolves and the Premier League club West Bromwich Albion — are now Chinese owned. “Off the pitch, they [Fosun] have been fantastic,” says Mr James, a season-ticket holder for 30 years. “They have been listening to the fans. They want the fans back.”

The unfashionable club, 140 miles from London and in a region that has been in decline for decades, seems like an odd investment for Fosun. Although profitable, Wolves’ revenues are unlikely to make much of an impact at its Shanghai-based parent company, better known for its pharmaceuticals business, real estate and assets like Club Med and Cirque de Soleil.

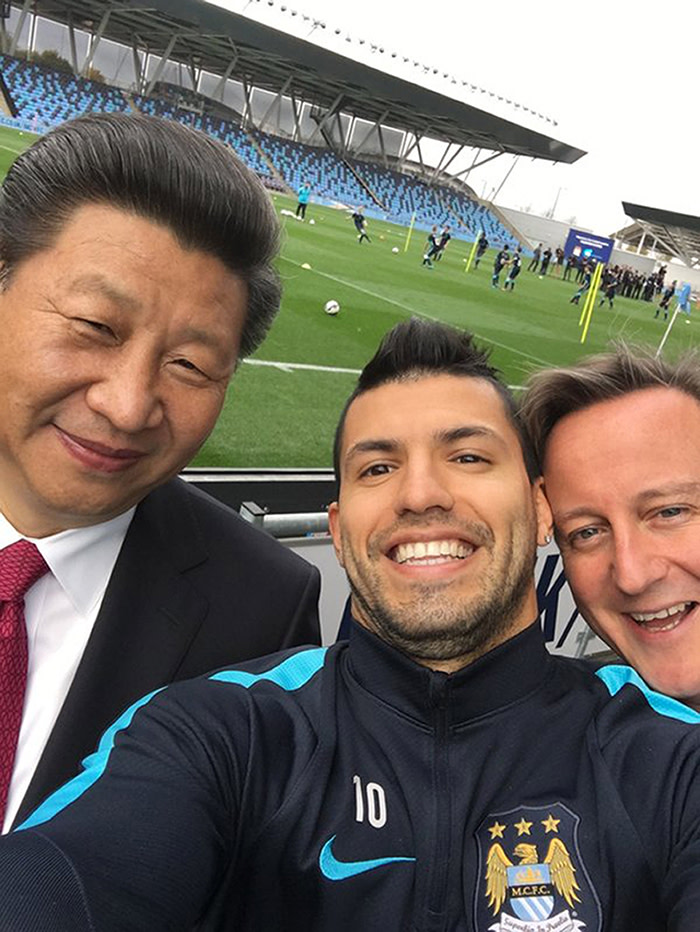

Bankers say tycoons like Fosun’s Guo Guangchang were keen to win the favour of Mr Xi, a football fan, and help China acquire the overseas experience needed to develop the domestic game. In 2015, Mr Xi launched a sweeping plan to turn China into a football force to embody his muscular vision for the “great rejuvenation” of the nation. Boosting China’s influence in the world’s most popular game is part of a wider push to increase the country’s soft power and earn China its rightful place on the world stage.

Many of the tycoons who leapt into football also had their own financial motivations, hoping to take advantage of cheap financing to buy clubs before selling them on for a profit. But the financially fragile and emotionally fraught world of European football carries risks for the Chinese Communist party and politically connected tycoons.

Fearing that the surge in deals was getting out of hand, the government started to tighten scrutiny of overseas sports acquisitions at the end of last year. In August, it formalised a wider crackdown by restricting investments in sectors that had seen a flurry of what it deemed “irrational” deals including property, cinema and sport.

Having sparked the initial investment frenzy, Mr Xi had grown wary of his name being used to justify questionable deals, according to two senior executives active in Chinese football. “Originally everyone thought that so long as the Emperor likes it, we can do anything in football,” says one of the executives, referring to Mr Xi. “But they forgot that the Emperor also has to be careful about financial risks in the system.”

Mr Xi’s goal to turn the world’s most populous nation from a football backwater into a “great sports nation” is extremely ambitious. He wants to build thousands of soccer schools, host the World Cup and transform the national team, ranked 57 in the world, so it can hold its own at the sport’s premier international tournament.

The “extensive development” of competitive sports has helped boost the appeal of China’s “underlying values” and increase its “soft power and international influence”, Mr Xi told delegates at the Communist party’s five-yearly congress last month, where he was confirmed as the country’s most powerful leader since Mao Zedong. “The wave of positive energy felt throughout society is building,” he said.

China’s president is not the first authoritarian leader to see the promotion of sport as a way to win popular support at home and burnish the country’s image overseas. But the scale, ambition and financial backing that Beijing brings to key state projects is on a level that is already transforming global industries from robotics to solar.

Exporting soft power is difficult for China’s Communist party because its overt rejection of democratic values and intensifying clampdown on criticism project a harder edge overseas. Football, which lacks the political complications of other sectors like media and education, should be an easier win.

“There is a lot of cachet in Chinese [buyers] acquiring football assets in the west,” says Jonathan Sullivan, a political scientist at the University of Nottingham who is researching the country’s sporting ambitions. “It is a good look for China to be involved with famous global cultural assets like Atlético Madrid or AC Milan.”

The estimated $2.5bn invested in European clubs in the past three years pales in comparison to the $220bn that Chinese companies spent on outbound acquisitions in 2016 alone, a record year for such deals. But the calculation is that football is more likely to win the hearts and minds of the local population than buying sewage treatment plants or factories.

“It’s about soft power,” says a second Wolves fan. “It’s about coming in and investing in a neglected area that’s been overlooked for years. People in the West Midlands like the Chinese. They’re seen as a moneyed, successful people. They are doing a lot more for us than the British government.”

However success is notoriously fickle in football. Previous waves of European football club acquisitions by US, Russian and Middle Eastern buyers have done little to improve perceptions of those countries. Will China be any different?

The investors range from prominent tycoons, such as Mr Guo of Fosun, Wang Jianlin of Dalian Wanda (Atlético Madrid) and Li Ruigang of China Media Capital (Manchester City), to little-known businessmen like Chen Yansheng (Espanyol), Tony Xia (Aston Villa) and Li Yonghong (AC Milan).

The motivation of some investors is clearer than others. CMC, Wanda and Fosun see European football as a high-profile element of growing media and entertainment businesses. Other deals appear to have fewer synergies and are driven more by opportunism.

“Some investors are intelligent and have business plans,” says Alex Jarvis of Blackbridge Cross Borders, one of several investment advisory companies trying to profit from the Chinese football M&A boom. “Some are completely reckless, don’t know what they’re doing and have bad advisers.”

Espanyol, Barcelona’s second team after their eponymous rivals, looked like one of those whimsical deals when it was acquired by Rastar Group, a manufacturer of remote-controlled cars, in 2015. But Robert Wong, a senior executive at Rastar, says Mr Chen, the company’s chairman, saw football as part of a broader expansion into entertainment, alongside the purchase of a gaming company.

After rescuing the club from financial difficulties , Rastar kept most of Espanyol’s management in place and returned the club to profitability. “Our results are better, and we play a more watchable game, as the fans have recognised,” says Mr Wong. “Sometimes when we play at home, if Mr Chen is around, you will hear them cheering his name.”

Those appreciative Espanyol fans, and supporters of other clubs scattered across Europe, may be surprised how much their team’s prospects are affected by the vicissitudes of Communist party policy. The crackdown on outbound acquisitions has shaken Chinese football investors.

They thought they would win political capital and favourable financing for supporting the football ambitions of Mr Xi. Now they are fearful.

“Given the direction of policy these days, we want to downplay our involvement in overseas football,” says one investor, sheepishly.

Lin Feng, chief executive of DealGlobe, which advised Chinese tycoon Gao Jisheng on the £200m acquisition of English Premier League side Southampton, says the government was spooked by the high capital outflows. He thinks it will be very difficult for new buyers to complete football deals, unless they can raise the funds outside China.

In addition, the investment banker warns that several Chinese businessmen, who relied heavily on borrowing to fund their football club purchases, could face fresh problems if, as seems likely, their plans to float their clubs as listed companies in the mainland are blocked by regulators.

AC Milan, the seven-time European champions, was one of the clubs hit hardest by the shift in Chinese policy. A consortium led by Mr Li, a little-known businessman, had already paid a non-refundable $117m deposit to Silvio Berlusconi, the former Italian prime minister and the club’s then owner, when the restrictions on outbound deals hit.

Mr Li was hoping to raise financing in China before cashing out later through an initial public offering, say people familiar with the deal. The crackdown almost derailed the acquisition and he had to turn to an expensive source of foreign funding, borrowing from US hedge fund Elliott Management, which is known for its activist approach.

“The dream is big, the reality is tough,” says Mr Feng. “Many Chinese acquirers are overpaying for assets and are not doing the post-merger integration well. So some of these guys will become sellers.”

Bankers expect the flood of Chinese football deals to slow to a trickle in the next couple of years, unless the government reverses course. It will be some years before it is clear how far they have helped, or hindered, the ultimate goal of boosting China’s international profile.

The spending spree has, however, already imprinted China’s economic power in the minds of hundreds of millions football fans. It has also revealed a weakness in China’s politically driven and opaque system, as opportunistic entrepreneurs try to capitalise on a government policy prone to U-turns.

It means the fate of Mr Xi’s plan lies in the hands of quirky characters like Mr Xia, who runs a range of businesses from the production of food additives to the design of smart cities. The outspoken Aston Villa owner has attracted more than 100,000 followers to his Twitter account, where he has asked for advice on player transfers, earned an English Football Association fine for criticising a referee and quoted Mao.

For Mr Xia and other Chinese owners, especially those who have borrowed heavily to back Mr Xi’s ambition, a more pressing question is whether their teams will achieve the success necessary to cover their costs.

There are also growing political risks for some of these tycoons, with Mr Xi’s anti-corruption campaign this year ensnaring businessmen previously thought to be untouchable. Mr Guo disappeared suddenly for four days in 2015 when he was questioned as part of a graft investigation and both he and Mr Wang of Wanda have this year had to deny rumours that they were again detained in connection with corruption investigations.

“Some of the Chinese investors who have bought foreign clubs are not in great financial positions,” says Mr Sullivan. “If a Chinese owned club goes belly up, especially a high-profile one, that is a bad look for China.”

Additional reporting by Rachel Sanderson in Milan

Chinese Super League: High-profile transfers spark domestic support

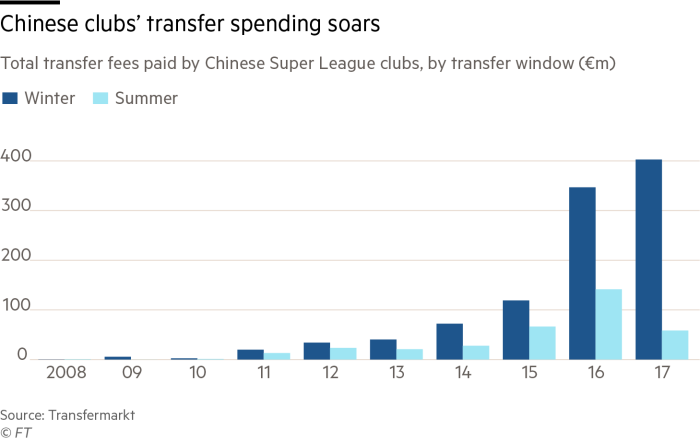

If the $2.5bn spent on buying up European clubs over the past three years has captured international headlines the investment in China’s domestic league has been no less spectacular. Tycoons have pumped several billion dollars into the Chinese Super League in response to President Xi Jinping’s call to transform the game, recruiting top players like Carlos Tevez alongside managers including Luiz Felipe Scolari.

At the start of this year, however, the sporting authorities applied the brakes and called for clubs to stop “burning money” on “irrational transfers”, after CSL teams spent more than $450m on transfer fees last year, more than double the figure in some European leagues including France. It also introduced limits on the number of foreign players allowed to play in each game, to give more opportunities to Chinese footballers.

Average attendances have risen by more than 60 per cent since 2010 to nearly 25,000 this year and more people now go to the average CSL game than top-flight matches in the French and Dutch leagues. Sky Sports, the British broadcaster that transformed English football by pushing up the value of TV rights, started showing the CSL last year, in a sign of growing global interest driven, in part, by the star signings.

But its future trajectory may be more slow and steady. Nicky Wong, vice-chairman of CSL club Guangzhou R&F, warns that the “government-led enthusiasm for football is not sustainable” because all CSL clubs are currently lossmaking.

Dragan Stojkovic, the R&F coach, says China will have to be patient as it takes decades to build a football culture.

His strategy of developing young players and picking bargains in the global transfer market has paid off, with R&F finishing fifth in the season that ended last weekend, despite a far smaller budget than its rivals.

Comments