Pioneering Kenya eyes next stage of mobile money

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Kenya has led the African continent in financial innovation for more than a decade with its revolutionary mobile money service M-Pesa, used by two in five Kenyans. Now its entrepreneurs are seeking to use the country’s love for mobile payments to solve bigger economic problems.

Mobile money was just the “first step”, says Ken Njoroge, co-founder and co-chief executive of digital payments company Cellulant. The second, he continues, was digital lending. “Only when you get to the third tier, when you take these products and assemble them together to really solve a huge economic problem in the market do you make real progress.”

In the second of the half the year, Mr Njoroge’s Nairobi-headquartered company will launch Agrikore, a digital payment, contracting and marketplace system that connects small farmers in Kenya with large commercial customers.

Agrikore is already up and running in Nigeria, and Cellulant believes the system can unlock the vast potential of Africa’s fragmented agricultural sector and deepen the reach and impact of financial services for the continent’s 1bn people. “To really win the financial inclusion battle in Africa, you build it in agriculture and then replicate,” he says.

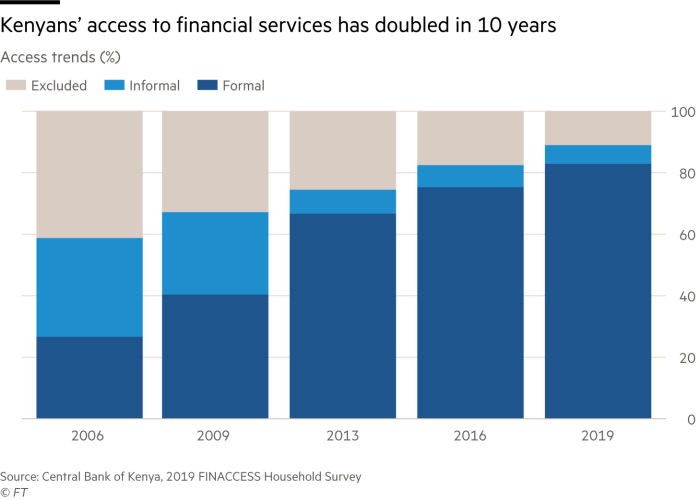

Kenya is a perfect test case for both the potential and the limits of traditional efforts to expand access to financial services. More than 80 per cent of Kenyans now have access to financial services — defined to include those offered by banks, microfinance providers and mobile money providers — up from 27 per cent in 2006, according to a survey published this month by Kenya’s central bank. In the capital Nairobi, financial inclusion is as high as 96 per cent.

But despite the rapid progress in access to financial products, the impact on daily lives has been modest. When financial problems arise, more than 60 per cent of Kenyans still turn to informal borrowing — from friends, families and loan sharks — and more than two-thirds of Kenyans say they are still unable to meet their daily expenses in each income cycle.

“Many Kenyans have formal accounts in various forms, but these accounts are rarely used because they are not solving real day-to-day problems for many households, smaller and micro-scale businesses, and farmers,” Patrick Njoroge (no relation to Ken Njoroge), the governor of the central bank, said in the report. In short, simply having access to a bank account does not lift someone out of poverty.

Cellulant’s Mr Njoroge, who was named east Africa emerging entrepreneur of the year in 2018 by the consultancy EY, says that his company’s agriculture platform will solve one of the governor’s “real day-to-day problems”.

Smallholder farmers face three challenges, he says: low productivity, poor access to buyers and opaque pricing. Agrikore aims to solve those problems by creating a “meticulous catalogue” of what each farmer grows, in what season and at what volume.

When Agrikore’s commercial buyers make large orders on the platform, the algorithm slices up the request based on capacity and proximity and sends out text messages to individual farmers requesting a volume of a certain product, on a certain day, at a certain price. Once the farmer accepts the offer, the system triggers a series of other activities, matching the farmer with registered transporters and quality inspectors who all log their activities via the platform and are paid via Cellulant digital wallets.

The technology delivers an “Uber effect”, Mr Njoroge describes, “taking all of these little disconnected pieces between demand and supply and then just bringing the elegance that technology can bring to connect all those pieces”.

He adds: “All of these inefficiencies that you take out of the system result in a better price for the farmer and a better price and more consistent supply for the buyer.”

Other digital companies are working to extend the reach of Kenya’s mobile payments systems in other ways. DPO Group — one of Africa’s biggest payments companies, also headquartered in Nairobi — will this year, in partnership with Mastercard, launch a “virtual card” that can be topped up with mobile money. Customers will be given a 16-digit number, expiry date and security code so that they can use the digital account globally in a similar way to a debit card.

Though mobile payments like Safaricom’s M-Pesa — which was launched in 2007 — are increasingly used in Kenya to pay for goods and services, few international companies accept the country’s mobile money, including new entrants into the Kenyan market such as streaming service Netflix and ride-hailing platform Uber.

Mobile money transactions reached Ksh3.7tn ($38.5bn) last year, according to Kenya’s central bank, equivalent to almost half the country’s gross domestic product, but it remains a predominantly local payment solution, says DPO chief executive Eran Feinstein.

Linking mobile money with traditional card payment methods will help Kenyans transact not just with each other but with the rest of the world, he says. “Mobile money is only the beginning.”

Comments