Catherine Petitgas: ‘Collecting is not about decorating’

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Catherine Petitgas refers to herself, more than once during our conversation, as a “Stakhanovite” — someone exceptionally hard-working and diligent. That and her natural warmth and enthusiasm add to her standing as one of the most influential art collectors and patrons in London.

The list of her achievements is quite something: chair of Tate International Council, member of its Latin America committee, former trustee of the Whitechapel, chair of Gasworks, member of the Serpentine gallery council, “founding godmother” of the Anglo-French Fluxus Art project, editor of art books, art historian, briefly a gallerist, Tate guide. And that is just a partial list. In a previous life she was a successful equity analyst on Wall Street.

“I really enjoyed my time as a bank analyst, but there came a point when I needed other priorities, I couldn’t imagine doing another 10 years in finance,” she says, laughing.

She laughs a great deal during our conversation in her stylish townhouse, overlooking a garden square in Kensington. She speaks perfect English with a noticeable French accent — and also speaks Spanish and “colloquial Arabic” plus a smattering of other languages.

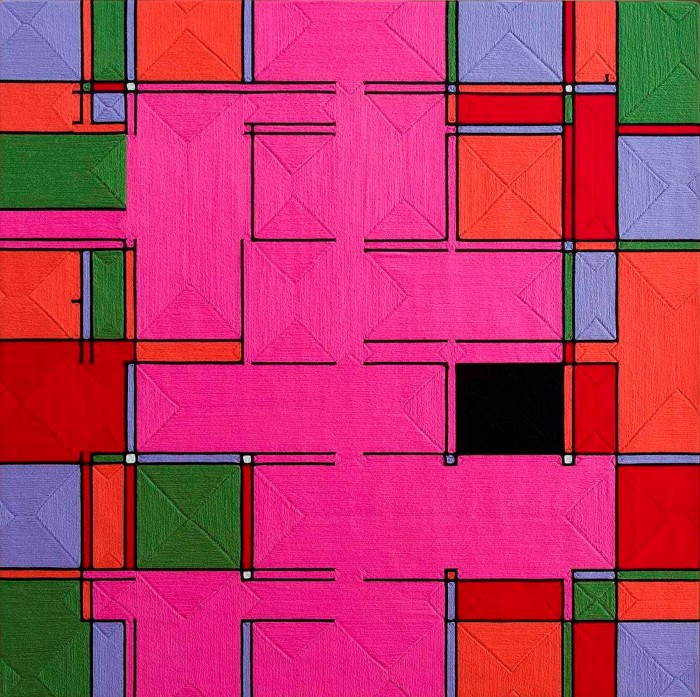

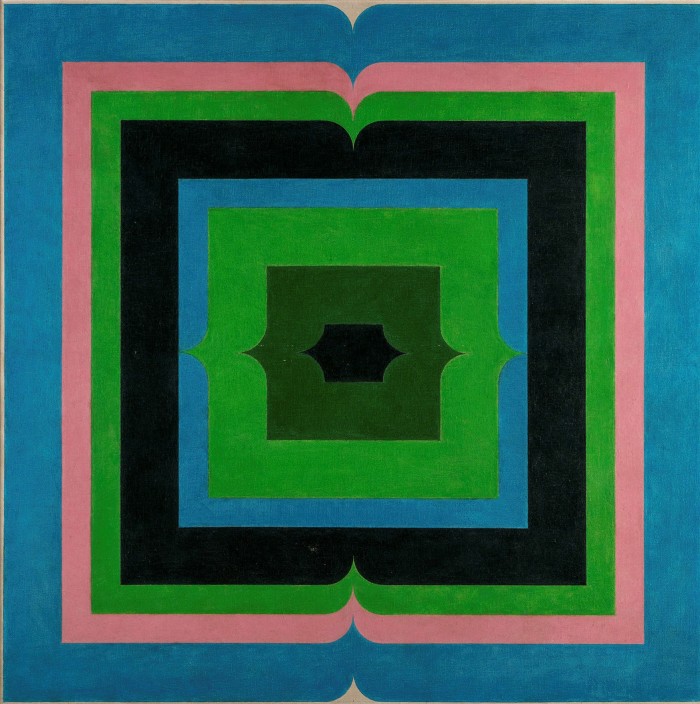

Wearing a signature Issey Miyake pleated dress in black and grey and outrageous grey-and-black platform boots, Petitgas settles into a low sofa in the library. Over the fireplace is a “Mexican pink”, green and orange work by the Mexican artist Eduardo Terrazas, made of woven yarn glued with beeswax. “It is a geometrical composition, inherited from Mondrian, but he would never use those colours,” she explains. Elsewhere in the house works by Gabriel Orozco, Beatriz Milhazes, Josef Albers, Jorge Pardo, Sheila Hicks and Ivan Serpa are hung in an elegant, uncluttered display which allows each work to breathe.

Petitgas’ year in Mexico City, when she was in her early twenties, was what she calls a “defining moment” in her life. She had just graduated from one of Paris’s highly competitive business schools, after a childhood in north Africa. “They didn’t know what to make of me in Paris, an exotic creature, always late, not used to the grey skies,” she laughs again. At the school she had taken an option in 20th-century American art and was “blown away — that’s what sparked my interest in art”.

After Mexico she returned to Paris and studied at Sciences Po university before moving to New York to become an equity analyst. “I saw a work by the Mexican artist Gabriel Orozco in 1993, at MoMA, and it was just oranges placed on windowsills. You had to look out of the museum at them and I thought, ‘this is the art of today’. It forced you to look at the mundane things around us. That was another defining moment.”

After leaving her job in finance and moving to the UK, Petitgas briefly ran a gallery (“I thought it would be easier than it was . . . I do admire gallerists, it’s a tough life”) before deciding to go back to school — again. She found the time to do a Christie’s course, then a MA in the history of modern art at the Courtauld Institute before becoming a “Millennium Guide” for Tate Modern, which was about to open. “I really enjoyed guiding for Tate, and it was just when Modern had opened, it was such an exciting time.” She says that experience triggered her “militant approach to being a patron of the arts”.

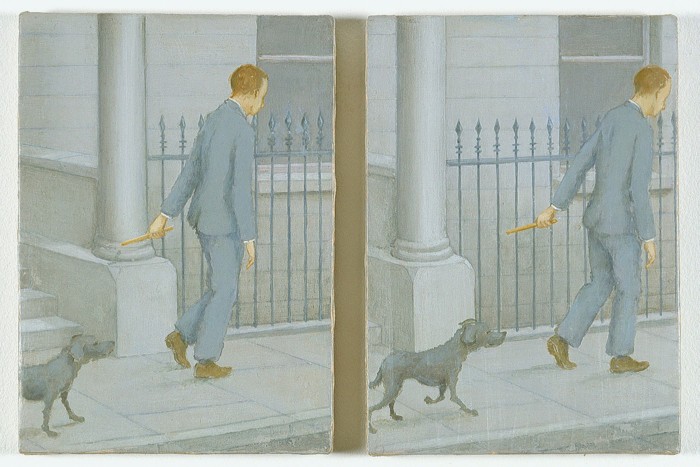

She and her then husband Franck had started collecting art, notably by the Belgian artist Francis Alÿs, who also spent time in Mexico City. After moving to the UK, they continued to collect art, notably by Alÿs, which is how they met Nicholas Logsdail of Lisson Gallery. “He was curious about us, he insisted on coming to our house . . . and I could tell he was deeply disappointed by our collection! I confess we were a bit miffed.”

Petitgas realised that “collecting is not about decorating” and decided to be more ambitious in her aims. She chose to concentrate on Latin American art and started a long-term policy of patronage. The first gesture was when she contributed to Alÿs’s project for Artangel, Seven Walks (2004-5). Since then she has funded many projects for museums including Chisenhale and the South London Gallery.

“For me, collecting is enabling institutions to keep doing good exhibitions, helping galleries and keeping artists working,” she says. She says the experience of sitting on museum boards and committees has been immensely rewarding: “You get privileged access to the curators, you learn how institutions collect, what their thought processes are.”

I ask if the pandemic has seen more knocks on her door from institutions, and if she has responded. “Yes!” she says: “I am one of the three supporters of this year’s Tate Bursaries, under which 10 artists receive £10,000 awards in place of the 2020 Turner Prize.”

The generous patron has not gone unnoticed across the Channel. As she puts it, “French institutions have found me as well!” She is now vice-chair of the Friends of the Pompidou Centre, which buys works for the museum and supports its exhibitions. She also chairs Fluxus Art Projects, which supports emerging, unrepresented artists in the UK and France. Among its success stories are Laure Prouvost, who represented France at the 2019 Venice Biennale, and Anthea Hamilton, nominated for the 2016 Turner Prize.

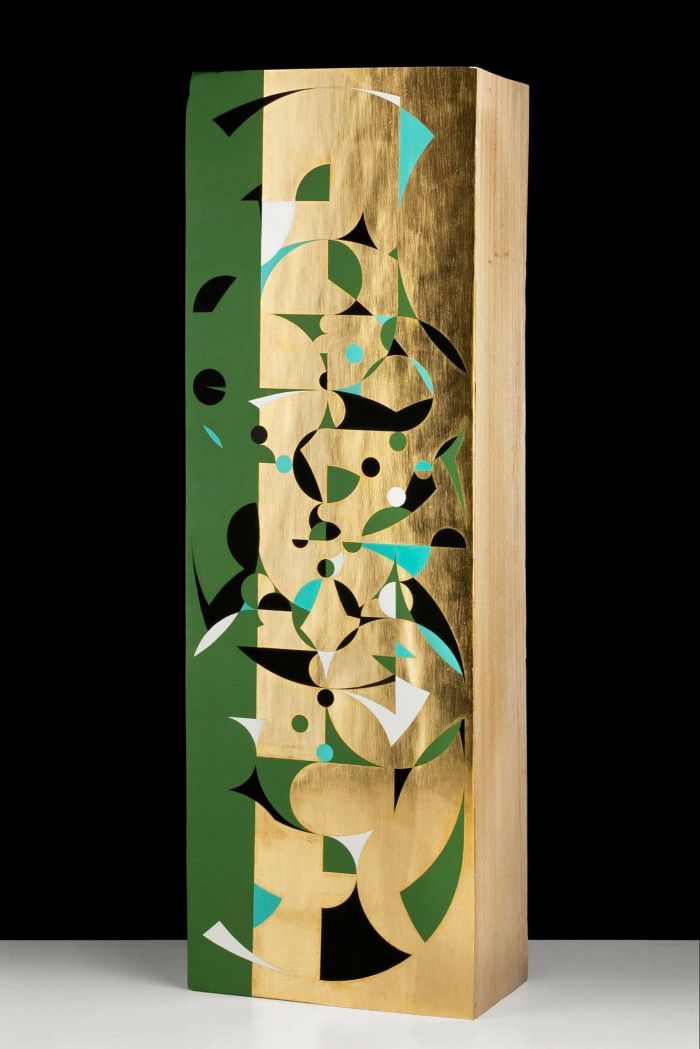

But contemporary art is not Petitgas’s sole interest. On an upper floor in her house she has a collection of surrealist paintings. Among these are works by Leonora Carrington, Dorothea Tanning, Remedios Varo and a small, precious Max Ernst (“I get the most requests for loans of these surrealist works,” she says). She also has a collection of British Constructivism, shown at Pallant House, Chichester, in 2017. Another interest is “concrete poetry”, text used on objects. A group on a landing in her house includes a colourful clock by Ken Cox which spells out the four seasons in its spinning hands (“Four Seasons Clock”, 1965).

Her collection now numbers some 1,000 pieces shared between her homes in Paris and London, some on loan, some in storage. I ask what their long-term future is. “The collection is alive, and I want to continue to contribute to the art scene by collecting and supporting as long as I am in good health and have the means to do so,” she says.

“I have a wonderful house in the Yucatán and have ambitious plans for establishing a cultural project there . . . and I am a strong believer in public institutions, for their didactic role, for their public access. I plan to give significant pieces to such institutions — and I hope that my son Victor, who is very interested in the collection, can carry on with it into the future.”

Comments