The Saudi Reshuffle: five key reforms in Riyadh

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The pushing aside of Saudi Arabia’s influential longstanding oil minister, Ali Naimi, has grabbed headlines around the world thanks to his position within global energy markets

But Mr Naimi’s retirement was part of a wider reshuffle that put in place the team handpicked by Mohammed bin Salman, deputy crown prince, to implement his ambitious reform programme, Vision 2030.

The plan aims to reorient the economy towards the private sector and away from statist dependence on oil revenues. The detailed road map for implementation of the Vision 2030, the National Transformation Programme, is scheduled for release within the next month. Replete with “ministerial dashboards” to track departmental achievements, the NTP will be entrusted to a trusted circle of technocrats.

Here are the five main areas of the prince’s reshuffle:

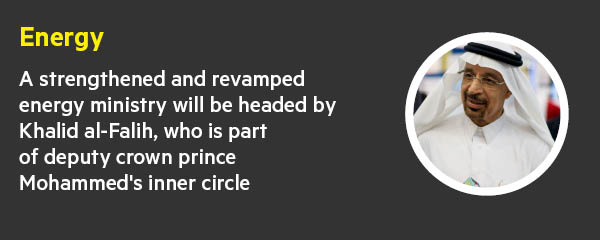

Ministry of Energy, Industry and Mineral Wealth

The key ministry of petroleum and mineral resources has been given the additional industry portfolio and will be headed by Khalid al-Falih, the respected Saudi Aramco technocrat who is part of Prince Mohammed’s inner circle of cabinet advisers. He will be a key interlocutor in the financial and intellectual centrepiece of the reform programme: the part-privatisation of oil behemoth Saudi Aramco.

Riyadh hopes that industrial development — in particular an expansion of manufacturing, which currently accounts for a quarter of non-oil activity — will help the private sector increase from 45 to 60 per cent of gross domestic product and slash unemployment from 11.6 per cent to 7 per cent.

Industrial production is currently concentrated in the oil-rich eastern province and is focused on chemicals and petroleum-related manufacturing. Linking industry to energy could capitalise on Saudi Aramco’s work over the past decade of developing “industrial clusters” around existing petrochemicals and petroleum industries. Energy, while more expensive since this year’s subsidy reforms, is cheap by global standards and remains one of the kingdom’s main competitive advantages.

Ministry of Water and Electricity

The ministry of water and electricity was thrown into turmoil last month when its head was sacked after Prince Mohammed criticised the manner that new higher tariffs were implemented. The ministry has now been split, with the water portfolio being incorporated into a new Environment, Water & Agriculture ministry; electricity will be part of Mr Falih’s energy ministry.

Despite his criticism, the prince remains committed to the reduction of energy and utilities subsidies, which are expected to generate as much as $30bn a year for the government by the 2020. But they remain a sensitive issue and could easily spark social unrest among a population that has long regarded cheap oil and cut-price utilities as its birthright.

Ministry of Commerce and Investment

The newly reconstituted ministry of commerce and investment has shed its industry portfolio — which is now part of the new energy “super-ministry” – and will be he headed by former social affairs minister, Majed al-Qasabi.

It has already enacted a companies law, which came into effect last week, promising new governance procedures, such as barring a chairman from holding executive positions. It also cuts business costs, including reducing the capital needed to establish a company from Sr2m to Sr500,000.

Investors are awaiting the unveiling of a new insolvency law, which will provide a comprehensive framework for restructuring companies in difficulty and includes new settlement and claim procedures. Currently, winding up a business in Saudi Arabia is difficult, with corporate debt often underwritten by individual directors who can go to jail for default. If the new regulation is successfully implemented it will be the Gulf region’s first modern bankruptcy framework, a legislative boon for the private sector and foreign investors.

While lawyers say work still needs to be done on the new legislation, any improvement on the status quo would help the Vision 2030 goal of increasing small and medium-sized enterprises’ contribution from 20 per cent to 35 per cent of GDP.

Central Bank and Public Investment Fund

Ahmed al-Kholifey has been appointed governor of the Saudi central bank, or Sama, as its ancillary role as warden of the state’s wealth is set to change with the transformation of the Public Investment Fund. The PIF, which was established in 1971 to hold stakes in local companies in an effort to develop the national economy, will take ownership of Saudi Aramco and become a $2tn sovereign wealth fund.

Sama’s reserves have dropped to $580bn over the past year and are being depleted at a rate of $10bn a month to help fund a fiscal deficit that his year is expected to reach as much as 19 per cent of GDP. The transfer over time of some of the bank’s assets to the PIF will change Sama into a more traditional central bank institution, supervising and pricing lenders’ regulations with less influence over investments.

Royal court adviser Yaser Alrumayyan, is tasked with managing the PIF’s transformation. The PIF will hold “national champion” assets with Saudi Aramco joining its existing portfolio of state holdings, such as petrochemicals giant Saudi Basic Industries Corp. The fund, which could raise debt on its large asset base, will “help unlock strategic sectors requiring intensive capital inputs,” according to the Vision 2030 document.

Commission for Recreation and Culture

Former health minister Ahmad al-Khatib has been appointed to head the newly created Commission for Recreation and Culture. A former investment banker who is close to King Salman’s immediate family, Mr Khatib has the challenging brief of opening up new entertainment options within acceptable boundaries of social change in the kingdom.

The 30-year-old deputy crown prince has dropped a number of hints about the need for social change in Saudi Arabia, although conservative clerics — traditional allies of the al-Saud — are expected to block attempts to liberalise some of the structures that frustrate the kingdom’s youthful majority

The Vision 2030 plan promised that the government would build “cultural and entertainment” projects, offering cultural venues, such as libraries and museums. It aims to double household spending on cultural activities and entertainment inside the kingdom to 6 per cent by 2030. Many Saudi families holiday abroad, with cinemas — banned in Saudi Arabia since the 1980s — one of the main attractions.

Comments