An election to decide America’s place in the world

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

When Nancy Pelosi told the world to leave it to Americans to decide the 2020 presidential election, she had Russia and China in mind. The Speaker of the US House of Representatives noted that American intelligence shows Moscow and Beijing are already trying to interfere in the process.

Washington’s adversaries are not alone in thinking they have a big stake in the outcome. Politicians and policymakers in just about every corner of the globe have been tuned into the campaign for months. With good reason. November’s contest will be as consequential for the world as any since Franklin D Roosevelt’s victories in the 1930s.

From a distance this looks like an election in two parts. In the first, Americans will choose who they want to govern them for the next four years. In the second, the US will decide between engagement or retreat, whether it wants to sustain its global leadership or would prefer to look on from the sidelines in the face of rising international disorder.

If the sympathetic Fox News and the antagonistic CNN are any guide, the first part is all about the character of Donald Trump. Is he the authentic champion of the working class, or a dangerous demagogue threatening the founding principles of the republic’s democracy? The president, as mesmerising a figure for his opponents as for supporters, sets and resets the daily news agenda. You back Mr Trump or you abhor him.

If this sounds unfair on Joe Biden, the Democratic party’s presumptive nominee should not take it as so. Mr Trump is Mr Biden’s best chance of winning. True, not so long ago the economy looked set fair. It seemed a reasonable calculation that enough independent voters could sign up alongside Mr Trump’s white working-class base to get him over the line.

That was before coronavirus put up in lights Mr Trump’s trademark mendacity and incompetence and the uproar over police brutality against black Americans teased out the president’s worst prejudices. Mr Trump lies about many things, but he cannot gainsay the tens of thousands falling victim to Covid-19 and the millions facing unemployment. Except for the ultra-rich, the answer in November to the fabled “are you better off” question will be a resounding “no”.

This week Mr Biden took a bold step by choosing California senator Kamala Harris as his running mate. The formidable Ms Harris is the first African-American woman to appear on one of the main parties’ presidential tickets. The Democrats’ policy platform will be on show at next week’s virtual convention. That said, I doubt that Mr Biden will worry too much if the campaign spotlight remains fixed on the question of Mr Trump’s fitness for office until election day. The president is flailing. Mr Biden’s route to victory is surely as no more or less than the solid, competent and moderate alternative.

The connection between this domestic debate and the second part of the election is at best tenuous. Foreign policy rarely looms large in such campaigns. This one seems unlikely to be an exception, even if Mr Trump thinks there are votes in ratcheting up pressure on China.

Vladimir Putin’s backing for Mr Trump is unsurprising. The US president seems infatuated with his Russian counterpart. China’s Xi Jinping is said to favour Mr Biden. By tradition Chinese leaders have preferred Republican “realists” over Democrats, who are more likely to pay attention to human rights. In this instance, Mr Xi may have concluded that anything is preferable to Mr Trump’s angry unpredictability.

America’s partners and allies have a bigger stake. For 75 years, most of them have prospered under a US security umbrella. Now, with the notable exception of a smattering of autocrats such as Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdogan or Saudi Arabia’s Mohammed bin Salman, most will cite any number of reasons for backing Mr Biden.

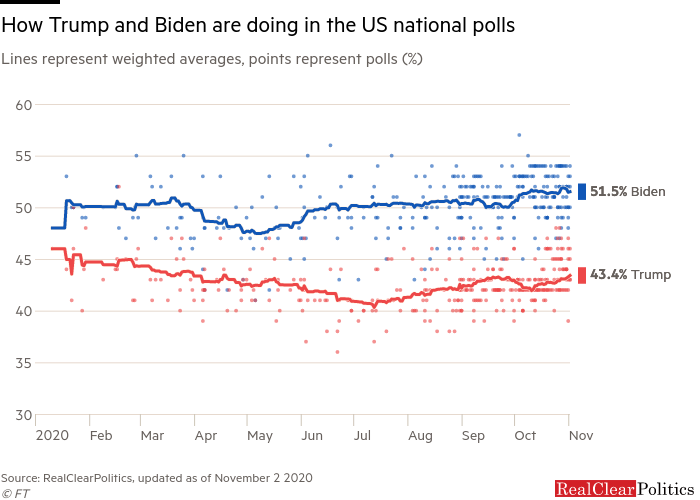

Trump vs Biden: who is leading the 2020 election polls?

Use the FT’s interactive calculator to see which states matter most in winning the presidency

Mr Trump is careless of America's friends, has pulled out of the Paris climate change accord, torn up the nuclear deal with Iran, undermined Nato, and replaced trade diplomacy with tariff wars and extraterritorial sanctions. “America First” has been a repudiation of the leadership assumed by the US after the second world war.

This last point is the one that really matters — one that distinguishes this election from all the others. The Pax Americana has run its course. The redistribution of global power, notably to China, means that the shape of the order that eventually replaces it is, for now, contested territory. The US can act as the convener of the world’s democracies, or it can withdraw to watch the old system dissolve into disorder.

The last time America chose between isolationism and engagement was during the 1930s. The economic recovery launched by Roosevelt’s New Deal marked a slow, bumpy return to engagement. A decade or so later the Truman doctrine set the American goal as global leadership. The nation’s enthusiasm for foreign entanglements has waxed and waned ever since, but the organising assumption has gone unchallenged.

Now that assumption is on the ballot paper in November. Has Mr Trump’s “the world can go hang” foreign policy been a dangerous but short detour, or have Americans lost sight permanently of the many advantages they have made from international leadership? That is quite a question.

Follow Philip Stephens with myFT and on Twitter

Comments