Does harvesting worker data lead to empowerment or exploitation?

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Ever since employees began clocking in and out on punch cards, companies have captured data on their workers.

Now, new workplace technologies — from smart badges that track office interactions, to sensors monitoring truck drivers’ performance — are generating mountains of data on workers.

But while this can increase safety and efficiency, some worry it could also result in unfair or abusive practices.

“It can cut both ways,” says Jeremias Prassl, Oxford university associate professor of law. He cites the wristbands that track the movement of workers shifting packages around a warehouse. “If it plots the most efficient line for you, that’s good. But if the same algorithm bullies workers into working extra hard, that’s bad.”

Moreover, as in the case of consumer data, a lack of clarity hangs over the question of who owns workplace data and what is being done with it. Some argue that giving workers more control over their data could bolster their negotiating power on conditions and pay rates.

“Most employees would know they’re being tracked for productivity,” says Michelle Miller, co-founder of US-based Coworker.org, an online platform that helps employees launch campaigns to improve their workplaces. “But there’s not an awareness of how that data is being used and what story it’s telling.”

She points to a range of software that can monitor and analyse everything from the tone of emails and the web searches employees make, as well as how they move around the office and the people they talk to.

“It rates your risk to the company — whether you might be looking for a job, whether you might be a whistleblower or if you’re engaged in workplace organising,” says Ms Miller. “It’s taking all this data from you and making predictions that you don’t know about.”

Similarly, companies can use the health data generated by wristbands and other workplace wearables to design fitness programmes. “But it delivers all this data about your health that you have no control of,” says Ms Miller.

While companies cannot require employees to wear fitness trackers, she adds, those who do not participate in such programmes are often locked out of company perks such as gym memberships or discounted health insurance.

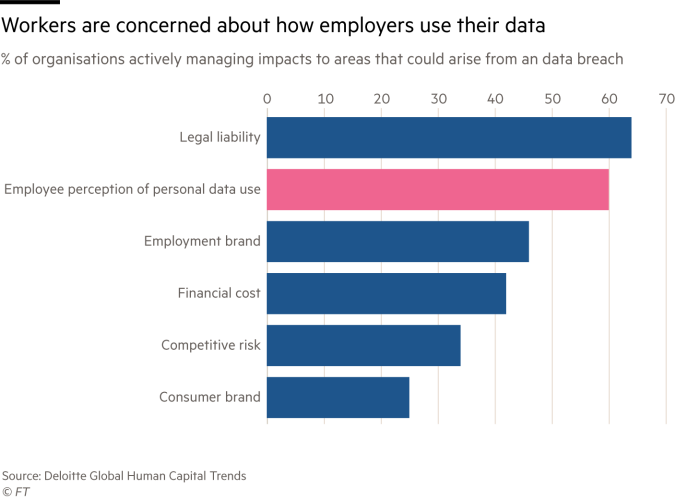

With the ability to collect and analyse increasing amounts of data on employees, companies are starting to worry about a potential backlash. Six out of 10 respondents to Deloitte’s 2018 Global Human Capital Trends report said they were concerned about employee perceptions of how their data is being used.

“Companies need to make sure they have robust policies on transparency and security and open communications, so people understand what is being tracked,” says Anne-Marie Malley, UK human capital leader at the professional services firm.

Legal challenges also pose a risk to companies when it comes to their use of workforce data. In the Deloitte survey, 64 per cent of respondents said their organisation was “actively managing legal liability related to their organisations’ people data”.

A recent wave of class-action lawsuits in Illinois suggests these concerns are well founded. Between July and October 2017, for example, employees filed 26 such lawsuits against employers for violating biometric privacy under the Illinois’ Biometric Information Privacy Act, according to Illinois Policy, a think-tank.

BIPA requires companies to secure a written release before a person’s biometric information can be collected and to inform them in writing about how and for how long this information will be collected, used or stored.

While BIPA, which was enacted in 2008, is an early example of legislation that can be used to govern workplace data use, more recent consumer data protection laws could be applied to workers.

This includes the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation, which gives greater rights to individuals over how their data is used.

“One wild card now being thrown in is GDPR,” says Mr Prassl. “That has the potential to shake up some of these longstanding assumptions about the right to data access, the right to explanations on use of data and possibly even ownership.”

Meanwhile, unions are starting to turn their attention to the collection of data on workers and the use of artificial intelligence in the workplace. Last year, the UNI Global Union, which has more than 900 affiliates worldwide and representing more than 20m workers, issued a set of principles to be used in union contracts and international labour rights standards.

These include the right for workers to have access to the data collected on them, including the right to have it corrected, blocked or erased, as well as the right to take it with them from job to job.

Data portability is particularly important for people working in the online marketplaces that make up the platform economy. In his book, Humans as a Service, Mr Prassl examines the opportunities and dangers of the gig economy and says online ratings are an extremely valuable asset for workers in this sector.

However, while workers may need protecting from discriminatory algorithms or breaches of their privacy, they could also harness workplace data to improve their negotiating power when it comes to conditions and pay rates.

This needs to be given far more attention, says Gavin Kelly, chief executive of the Resolution Trust. The organisation worked with Bethnal Green Ventures, an early-stage UK investor in technology companies that aim to address social problems, to create the WorkerTech initiative to advance pro-worker technologies.

“There’s no reason why the capacity to gather, use and analyse data instantly and at zero marginal cost couldn’t be of great benefit to people working in organisations as well as those running them,” he says.

Comments