Distressed debt investors still await rich pickings from pandemic

Simply sign up to the Financial services myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

A dozen years on from the collapse of Lehman Brothers, some of its remaining creditors received word that a payment would be coming their way.

The announcement last month that holders of two “enhanced capital advantaged preferred securities” issued by Lehman with a face value of $735m — though now trading at mere cents on the dollar — will soon receive $33m was a timely reminder that money can be made betting on even the most turbulent and convoluted bankruptcies.

Rummaging for bargains in the wreckage of failed companies is one strand of investment strategies known as “distressed debt” or “special situations”. It runs from making short-term bets on or against the debt of struggling companies, extending emergency corporate loans at juicy interest rates to seizing control of stricken but fundamentally solid companies through restructurings.

For some of the industry’s biggest players such as Apollo Global Management, Blackstone, Oaktree and Elliott Management, the last decade has been largely frustrating for their distressed debt businesses, thanks to rock-bottom interest rates and a resilient global economy.

However, the economic disruption unleashed by the coronavirus crisis is stirring hopes that the debt funds — and their investors — could be set for their richest pickings since the financial crisis, even though executives stress they will not be on the scale of a decade ago.

“It’s a moment in time where the opportunity set is so rich,” said Victor Khosla, head of Strategic Value Partners, a distressed debt investment group based in Greenwich, Connecticut. “But it is a once-a-decade opportunity, not a once-a-generation opportunity.”

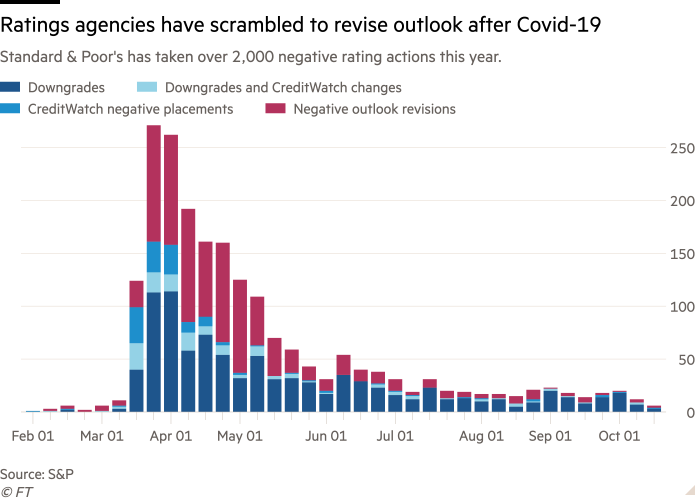

The chief reason for the industry’s more guarded optimism is the response of central banks — both in speed and scale — to the crisis. Led by the Federal Reserve, monetary authorities have bought trillions of dollars worth of bonds, easing borrowing costs for stricken companies.

Bank of America estimates that central bank asset purchases have globally averaged about $1.5bn an hour this year, containing what analysts say would otherwise probably be a brutal spike in corporate defaults.

As a result, even global junk bond yields have more than halved from a March high of more than 12 per cent to 5.6 per cent. US companies alone have issued about $2tn of bonds this year, smashing previous full-year records.

It is not just aggressive economic stimulus that is muddying the picture for distressed debt investors. The gradual erosion of the legal protections that creditors have traditionally insisted on means capturing the value in struggling companies may prove harder.

Many more indebted companies are controlled by private equity, which is likely to take advantage of laxer legal covenants to resist attempts to seize control of their investments.

As a result, industry executives say distressed-debt funds will be left to fight among themselves for the scraps, risking more protracted and bruising restructurings. The cases of US mattress maker SertaSimmons and California-based beachwear group Boardriders show how things can quickly turn ugly.

Hit by the pandemic, both companies sought financial rescues that left rival creditors jockeying to provide new loans. The creditor groups that were left out in the cold have since sued SertaSimmons and Boardriders, claiming the deals that were struck violated the terms of loans agreements and have unfairly cut the value of their debt.

Distressed debt investing used to be about “conducting diligence and making judgments on businesses,” said Ty Wallach, a longtime hedge fund investor who now runs the distressed debt group at Atlas Merchant Capital. Now it is more of a cut-throat legal game, he argues.

“So much more now is digging through documents to see how you can be leapfrogged. It’s a development in the market I don’t really like, because it can reward folks for being conniving.” It can, though, provide opportunities for those who know what to look for, he stressed.

And there are still plenty of overly-indebted companies that will struggle to stay afloat in the coming years, according to analysts. Satellite company Intelsat and car hire group Hertz are among those to have filed for bankruptcy this year. Both have viable businesses but unsustainable debt loads have given distressed funds the chance to creatively restructure them.

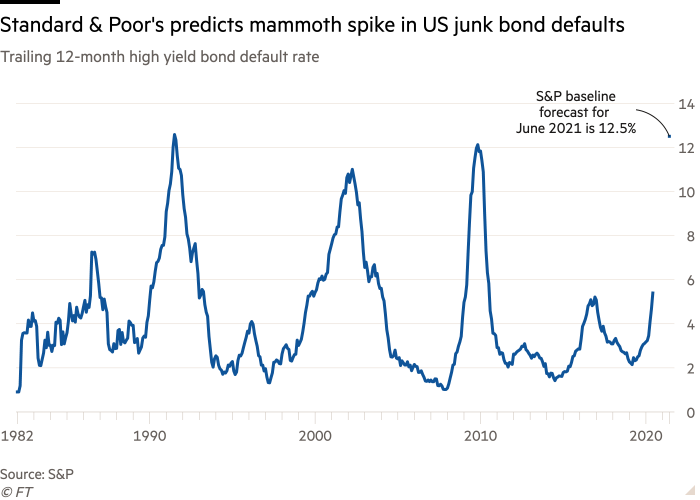

Fitch Ratings forecasts that the junk bond default rate will stay at about 5 per cent until 2022, for a cumulative, three-year default rate of 15-18 per cent. That compares with a three-year cumulative default rate of 22 per cent in 2008-10.

The IMF remains worried that many companies are fragile, warning in this month’s financial stability report of the danger of more bankruptcies if the stimulus-induced bond issuance boom fails to tide businesses over until economies recover.

Even this fails to capture the degree of distress among many companies that have not or cannot issue bonds, leaving them unable to benefit from central bank support and also facing a winnowing of government stimulus. Euler Hermes, the export-credit agency, expects corporate insolvencies to rise 35 per cent globally by 2021, the biggest spike since the financial crisis. “Covid-19 hit the global economy like a meteorite,” the company noted.

So far this year, hedge funds specialising in distressed debt have had little to trumpet, returning an average of 0.8 per cent, according to Eurekahedge, a data provider. But the strategy tends to struggle in the midst of a crisis — when prices for riskier corporate debt can be volatile — and fares better as an economic recovery builds. Distressed debt hedge funds, for example, notched up gains of 36 per cent and 23 per cent in 2009 and 2010 respectively.

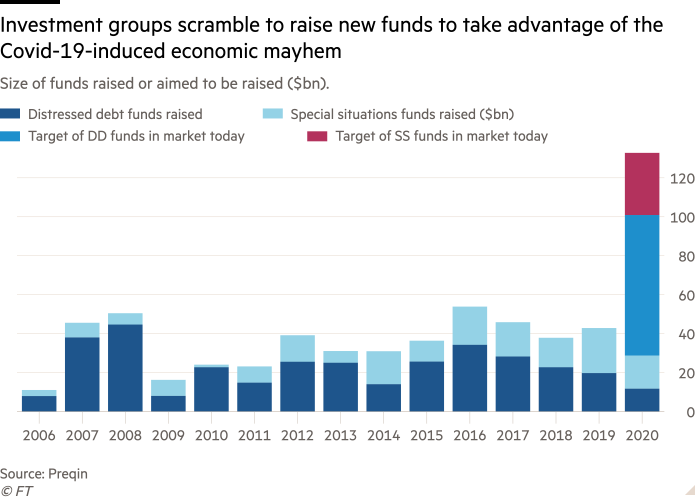

It is a history which means there has been a scramble to launch new distressed debt and special situations funds. Almost $29bn has been raised by 31 funds this year, according to Preqin. But a further 140 funds are currently tapping investors and targeting another $100bn. If even half meet their targets, then 2020 will be as notable a period for fundraising as 2008, the previous banner year.

“We like the landscape at the moment,” said Claire Madden, managing partner at Connection Capital, a UK investment group that funnels into distressed debt funds on behalf of its clients. “The problems are disguised due to various government schemes and money sloshing around the system. But going into 2021 there will be a lot of pain coming to the fore,” she added.

The data from Preqin does not include the launch of related strategies, such as opportunistic credit funds like Goldman Sachs’ new $14bn West Street Strategic Solutions, a cornerstone of the investment bank’s aim to build up its “alternative” investments business, and part of a broader industry effort to take advantage of the mayhem caused by Covid-19.

However, some executives argue the response of central banks and governments to this crisis has a lesson for the industry: secure more flexible mandates from investors and pounce more swiftly when investment opportunities arise.

Historically, a typical distressed-debt cycle might last for up to a year, giving funds plenty of time to deploy their firepower. But shorter, sharper bursts of distress are now more usual, which means that funds need to be faster. For example, Apollo invested up to $10bn in March, including all the capital held by the third instalment of its “dislocated credit” fund series Accord, and is now seeking to raise money for a fourth one.

“Central banks have really stopped the old business model where you could invest over a long period of time, by muting all the volatility,” said John Zito, co-head of Apollo’s global corporate credit division. “A lot of people have broadened their mandates, as they realise it’s very hard for them to use their old business model.”

While most say that mandates are becoming more flexible, some argue that the ability of central banks to repress volatility and turbulence in asset markets instead means that there will be a more subdued but elongated window of opportunity for investors to benefit from corporate distress.

“Central banks and governments have been very good at supporting markets and companies, but it cannot solve solvency problems, only liquidity problems,” said Remko van der Erf, co-head of alternative strategies at Kempen. “So the default cycle will be longer and more drawn out.”

Comments