Sleepless in the City — the man calming chief executives’ anxiety

Simply sign up to the Work & Careers myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

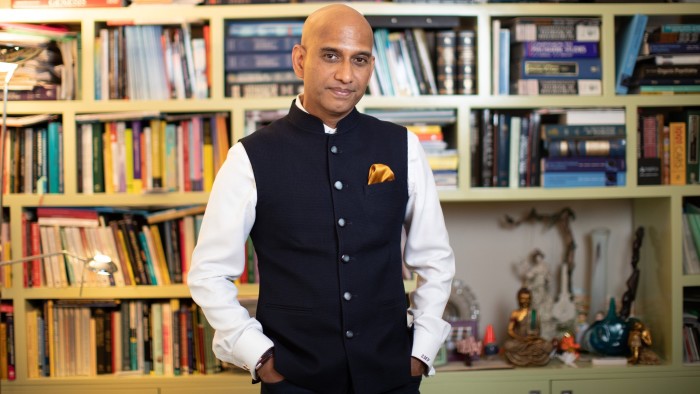

Stephen Pereira is calm; his voice is gentle and his speech, precise. As befits a psychiatrist and cognitive behaviour therapy specialist who attends to City workers’ mental health disorders.

Clients who have gone public about seeing him include Prince William’s brother-in-law James Middleton and the broadcaster Tom Bradby, who described in a recent interview how the insomnia that forced him to take almost five months off from ITV News At Ten was “ten times more frightening” than his experience of being shot.

Dr Pereira was asked to mentor António Horta-Osório, chief executive of Lloyds Banking Group, after he received treatment for chronic insomnia in 2011, a condition he likened to torture. Later Mr Horta-Osório said that Dr Pereira helped him to become “more like a palm tree, so when the storm comes the palm tree bends but then comes back up, instead of being like an oak tree and trying to resist the storm, in which case it can break”.

From his private clinic in London Bridge, just over the river from the Square Mile, Dr Pereira, who trained in psychiatry in Mumbai in the 1980s, and later at the Institute of Psychiatry at the Maudsley Hospital, Oxford university and King’s College London, has seen attitudes towards mental health change in recent years. There is growing acceptance, he says, that mental illness has “parity” with physical problems.

This change is demonstrated by the formation in 2013 of the City Mental Health Alliance, a group of legal firms and financial companies that shares best practice. Today, companies are keen to promote their mental health policies, and encourage senior leaders to talk about their own problems.

Dr Pereira says “there wasn’t open discussion [in the late 1990s when he moved to London] . . . Many corporates now, as compared to then, are taking a more proactive step in talking about mental health. Back in the late nineties, people didn’t even have a properly defined mental health policy at work, and there was very poor training in human resources or employee relations in this space.”

Mental health was the “very, very poor country cousin of the rest of the medical services”, mirrored by government policy that directed money towards cancer and children. When it came to treating the mind, the attitude, he says, was more likely to be: “Why don’t you just pull up your socks and get on with it?”

There is still some way to go, however. Good corporate policies do not filter down to the ground. Often, they are superficial, concealing poor work practices and unsupportive line managers. Too often, says Dr Pereira, discussions and reporting of mental health lack nuance — it would be unthinkable, he says, to discuss physical health in the same way, as if a heart condition is comparable to stomach pain.

Overworked doctors have developed an over-reliance on prescribing pills for treating anxiety, insomnia and depression, something that Dr Pereira says “has evolved as an unsatisfactory artefact of the system” — one that does not allow doctors much time for their patients who are “in need and therefore some distress”.

Many patients, are prescribed medication, he says, “who do not have biological or clinical depressions but may have . . . depression due to situational factors or life stresses”. Access to publicly-funded cognitive behavioural therapy is very patchy. “It turns out to be more like problem-solving sessions rather than proper therapy sessions.”

His private practice started as intellectual — and presumably, financial — relief from his work that helped people with severe mental illness, having set up in 1996, together with a couple of colleagues, the National Association of Psychiatric Intensive Care Units. “That was really heavy duty work,” he reflects.

Over the decades, Dr Pereira has seen “very many more people with anxiety disorders, with panic related disorders, with relationship difficulties, with sleep difficulties and with drinking”. It is difficult to discern whether this reflects increased problems or just growing awareness of the issue. As Scott Stossel, author of My Age of Anxiety, writes: “trying to directly compare levels of anxiety between eras is a fool’s errand. Modern poll data and statistics about rising and falling levels of tranquilliser use aside, there is no magical anxiety meter that can transcend the cultural particularities of place and time.”

City workers are not the cokeheads of popular mythology, Dr Pereira says. However, self-medicating with alcohol is a problem. “You start off with one glass of wine per day and then there comes a point when you require one bottle a day, or two, to achieve the same effect.”

Bouts of stress or nerves, before a presentation for example, are not necessarily debilitating. “Stress is not a dirty word. Everyone recognises the flutters,” he says. Where it becomes problematic is when it becomes severe, perhaps leading to panic attacks.

Poor management can aggravate employees’ mental health. “Many people in the City are promoted on the basis of their ability, their skill to generate revenue or to deliver on a particular project.” They are not necessarily equipped to manage others’ behaviour and emotions.

The unrelenting pace of City working is also damaging. “You don’t race a racehorse every single day of the year. When you put [employees] into one project after the other after the other without resting them in between, deliberately so, then you land up with . . . stress.” The prevailing attitude, Dr Pereira says, is that employees are replaceable. “If this cohort of racehorses are burnt out, we’ll get the next cohort of racehorses. But there’s so much time, effort, energy and money that is lost in terms of valuable experience and resources.”

Dr Pereira has seen various CEOs with stress-related issues . “By the time you get to be a CEO, one can develop blind spots. And then not being aware of those blind spots . . . can then become an impediment.” Fixing these is important, he says, because hiring a CEO is expensive and their decisions affect thousands of employees. Perhaps unsurprisingly, he argues that CEOs need mentoring from someone with psychological training.

Overall, prevention rather than cure is his goal. Dr Pereira believes that programmes such as “Optimal Leadership Resilience”, a course he helped devise at Lloyds, are the best strategy, equipping staff with psychological resilience and strategies to identify signs of stress.

Mr Horta-Osório says he wanted to work with Dr Pereira and his team of psychologists to design a programme that would help leaders to build better awareness about their mental health and adopt better habits. While the bank still has “a great deal to do”, he says that so far, efforts have led to “real, measurable progress” and the ambition is to continue to “encourage open, honest conversations on the topic”.

So far, 200 senior leaders at Lloyds have been through the year-long programme. The course includes personality inventories, development goals and self-reflection. There is also nutritional analysis, physiological monitoring, and resilience and mindfulness workshops. Lloyds is launching training based on the programme to 2,000 managers.

Dr Pereira wants companies to move away from “tick box” services to focus on prevention, encouraging employees to foster good mental health before problems become acute. “By the time [workers are] referred to me, the horses have bolted the stable doors,” he says.

How do you feel businesses should approach issues such as extreme stress, burnout, anxiety, depression and addiction in the workplace? Do you feel companies are doing enough? Share your experiences and ideas in the comments below.

Comments