Kazimir Malevich’s retrospective at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

In March 1927, the 48-year-old Kazimir Malevich visited Berlin for a retrospective of his work. When he returned to Russia in June of that year, aware that his prospects were bleak in a place whose rulers viewed non-realist art as debauchery, he left some 70 works behind in Berlin.

In 1930, convinced that he was a German agent, Soviet police arrested him. On his release, the founder of Suprematism, the most revolutionary abstraction yet invented, returned to figurative painting so as not to inflame state sensibilities. Desperate perhaps not to sully his reputation as a progressive, he sometimes misdated works to suggest that they had been executed before his abstract volte-face. Malevich died of cancer in 1935, convinced that his Suprematist oeuvre had been lost to the world.

As this magnificent exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam proves, Malevich was wrong. Although nearly scuppered by Nazism and the Allies’ bombs, his Berlin holdings survived and were acquired by the Stedelijk in 1958. Today, the Berlin works form the nucleus of this show. Our understanding of them is immeasurably boosted by the presence of drawings, paintings and sketchbooks gathered by Nikolai Ivanovich Khardzhiev, a Russian collector who moved to Amsterdam in 1993. Further illumination is supplied via works acquired by George Kostakis, a Russian collector of Greek origin, and now housed in the State Museum of Contemporary Art in Thessaloniki. Also present are works by Malevich’s peers Mikhail Larionov, Natalia Goncharova, Lyubov Popova, Olga Rozanova, El Lissitsky and Alexander Rodchenko.

The result is a meticulously mapped journey through the imagination of a titan of 20th-century art. Although Malevich’s genius was barely acknowledged until the 1960s, a group of his paintings found their way to MoMA in the 1930s, and his impact on Abstract Expressionism and Minimalism is undoubted.

Born in Kiev in 1879, Malevich was the son of a sugar refinery manager. In 1905 he enrolled at art school in Moscow. But his real lessons were imbibed through the French painters (Monet, Cézanne, Matisse, Picasso, Braque) assembled by Russian patrons Sergei Shchukin and Ivan Morozov.

The earliest work on show here, “Women with Newspaper in her Lap” (1904) – constructed out of white, shell pink, violet blues and pointilliste greens – is a soothing, Impressionist experiment that gives no hint of the tornado to come. But within a few years, his discovery of Symbolism’s dreamy possibilities, allied to an eye-stinging sense of colour that drew on Russia’s own tradition of folk and religious paintings, was giving an enamelled, icon-like potency to works such as “Woman in Childbirth” (1908) and “Shroud of Christ” (1908).

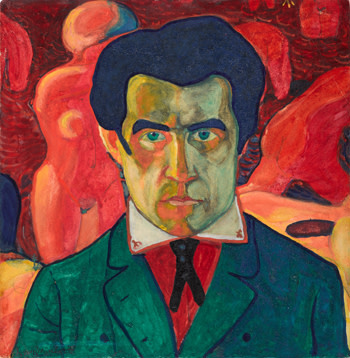

That intensity of expression unites his juvenilia. A telling self-portrait in 1908-10 conjures him as a green-eyed seer, his chartreuse complexion heightened with patches of tangerine, gazing out at the spectator with predatory power as mysterious flame-red nudes swoon in the background.

Malevich’s messianic energy drew him to Moscow’s avant-garde. Set on celebrating “the whole brilliant style of our modern times”, as Goncharova and Larionov put it, this was a generation for whom radical art was an expression of revolutionary politics.

Three paintings from 1912 show Malevich’s exaltation of the worker. Assembled from flat, cut-out planes, “The Mower” has a folksy directness; “The Woodcutter” is a silky, tubular machine-man for a brave new industrial world; the semiabstract “Head of a Peasant Girl”, her face unpeeled into curvilinear planes as if she were an anemone, shows an artist blessed with a gift for deconstruction.

Moscow’s poetry scene fuelled its art. Malevich was close to Aleksei Kruchenykh, inventor of “Zaum”, a form of poetry that sprang from the subconscious. Along with artist and musician Mikhail Matyushin, Malevich and Kruchenykh devised an opera depicting the imprisonment of the sun. On show in a screening room here, it’s a hilariously laboured affair. Yet as its archetypal characters – the Fat Man, the Certain Person of Bad Intentions – stomp about in casket-like costumes (designed by Malevich) reciting their bonkers libretto, it is a touching homage to the earnestness of its time.

This was also the incubator for Malevich’s leap to pure abstraction. Designs for the stage and costumes – a cubist pencil sketch invaded by mysterious black triangles, a plain backdrop divided by diagonal lines – show an artist increasingly distracted by the possibilities of pure form.

Two years later, all trace of the real had been vanquished. The highlight of this retrospective is the Stedelijk’s brave recreation of his extraordinary 0,10 exhibition in Petrograd in 1915. Comprising 38 entirely abstract paintings, its showpiece is “Black Square”, which Malevich mounted in the corner of the gallery, the place traditionally reserved for religious icons.

The paintings caused a scandal. (Critic Aleksandr Benois lamented: “All that we held holy and sacred [ . . . ] has disappeared.”) In our knowing age, of course, the impact is lessened. Yet overall, it’s hard not to be hypnotised by this constellation. Weightless exclamations of geometry that cling to their surfaces as if held by an invisible magnet, they are less images than manifestations of energy, or cosmic creatures from another dimension.

What exactly they signified for the artist remains an enigma. Malevich described Suprematism as the victory of colour and form over realism. He wrote like a poet – “I have destroyed the ring of the horizon” – and thought like a priest. Aside from the deliberate sanctification of “Black Square”, his paintings possess a mystic aura, as if religious iconography had been distilled to its abstract essence. A majestic series of crosses include “Suprematism of the Spirit” (1920), which sets a white square over a black cross sliced by a narrow red bar in an evocation of the Russian Orthodox symbol for Christ’s triumph over death.

Yet Malevich loved science too. Suprematism, he declared, was a hymn to the engineer, the only way to celebrate “the new beauty of modern life – great inventions, conquest of the air, speed of travel”. Like Italian Futurism, a sense of dynamism was at its core – yet unlike the frantic patterns of his Italian counterparts, Malevich conveyed motion through forms that were innately still.

The apotheosis of his career are his white-on-white paintings, four of which are on display at the Stedelijk. Trailblazers of monochrome abstractionists such as Yves Klein, Ad Reinhardt and Robert Ryman, their discreetly gestural brushstrokes and prism of interior colours – violet, pewter, snow, pearl, buttercream – triumphantly justify Malevich’s conviction that white symbolised “pure action”.

After reaching this zenith, Malevich declared that “there was no place for painting” any more. The second half of this show tracks him as he turns his attention to inventing utopian architectures, which he described as “planits”, in the company of fellow idealists such as El Lissitsky.

By now, however, the notion of “art for art’s sake” was falling foul of Stalin’s regime. Malevich tried to accommodate the demand for an art that could apply to everyday life; his decorated coffee cup must be one of interior design’s most delectable icons. But by the time he returned from Berlin, the only way to survive was to return to the realism he had condemned 10 years earlier as a “psychosis”.

Given the electric essentialism of what had gone before, many of these post-Impressionist canvases feel like travesties. Yet one series – “Running Man” (1930), “Girl with a Red Pole” (1932-33), “Girl with a Comb in Her Hair” (1932), “Woman with Rake” (1930-1932) – stands out for the way the scenes are assembled from flat blocks of pure colour criss-crossed by horizontal bands. The ghosts of Malevich’s extinct utopia have become the bars of his prison.

——————————————-

‘Kazimir Malevich and the Russian Avant-Garde’, Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, until February 2 2014, stedelijk.nl

Comments