Beware the madness of markets

Simply sign up to the Investments myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

The siren call of minting fabulous riches from the tap of a share trading app recalls past speculative manias down the ages that all ended badly; misallocating capital, wiping out savings and scarring investors.

A 1,500 per cent surge inside three weeks in shares of GameStop, a struggling video game retailer that few had heard of before, will in time become a staple of university finance courses. The uprising of retail investors against a group of hard-nosed hedge funds is an extraordinary tale and one that will spark scholarly treatises and perhaps even the full Hollywood treatment.

In the meantime, the growing buzz around a retail army in the US that brashly touts its views and trading prowess via the social media site, r/WallStreetBets, has attracted a massive influx of new followers and a surge in trading volumes among retail brokers, notably Robinhood.

Signs of a predominantly US online trading movement are registering in Japan, Malaysia, Korea, Europe and the UK, with shares jumping in companies that were under assault from short selling hedge funds. The retail crowd also turned from GameStop this week and briefly sent silver to its highest level in eight years.

The sight of retail money pouring into equities when valuations have already risen substantially is historically a warning sign that a market top beckons.

That should be noted by any reader thinking about opening a new trading account. They don’t need to look far to see how the use of margin debt, sitting at a record level versus US gross domestic product, shows many investors are discarding a long term approach guided by fundamental asset values. Fear of missing out is a powerful force.

“There is nothing as disturbing to one’s wellbeing and judgment as to see a friend get rich,” wrote Charles Kindleberger, the author of Manias, Panics, and Crashes: A History of Financial Crises in 1978.

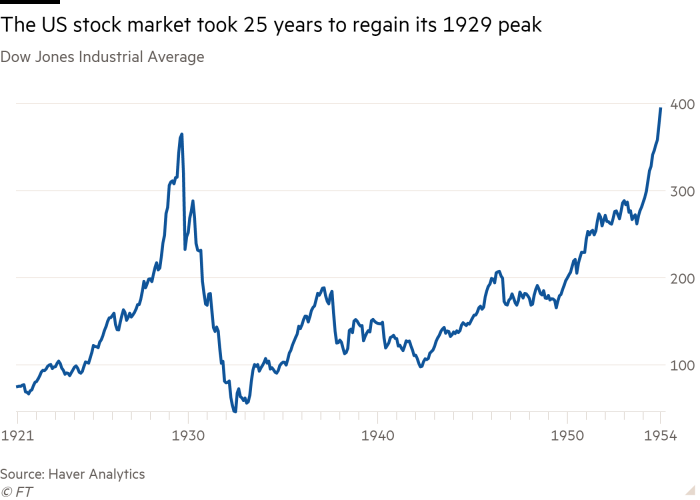

Envy scrambles the brain cells and persuades people that buying an asset at a new high makes perfect sense because the price will surely keep rising. This so-called “greater fool theory” defines the late stages of financial manias; tulips in 17th century Holland, the South Sea Company’s peak in London in 1720, gold’s tremendous spike in 1979-80, along with Japan’s real estate and equity booms of the 1980s. China has seen enormous speculative driven surges in the past decade, but pride of place rests with Wall Street and its epoch-defining manias.

A history of Wall Street bubbles

The roaring twenties marked a point when investors discarded a focus on dividends and asset values to obsess over the future trend of earnings for companies, observed Benjamin Graham and David Dodd in their first edition of Security Analysis published in 1934.

Buying good stocks and paying lip service to ever-rising valuations on the promise of their future earnings prowess powered Wall Street’s bull market of the 1960s and early 1970s, in the form of the “nifty fifty” stocks. Large US companies including IBM, Coca-Cola and General Electric were all-conquering in the eyes of investors until their high valuations popped in a savage bear market in 1973-4.

Topping that was the internet and telecom bubble during the second half of the 1990s. Another generation of retail traders embraced the idea that this time was different and you needed to own dotcoms that would have first-mover advantage in this new digital world. With the exception of Amazon, few delivered on that promise. Buyers of Intel and Cisco at the peak in 2000 are still waiting to see a new high.

Today, many look at the recent performance of bitcoin, the cryptocurrency that has regularly swung high and low in price, and frothy areas of the equity market and believe a similar pattern is being repeated. A prominent example is Tesla, whose shares have risen tenfold since March last year to value the company at $830bn, a market capitalisation beyond its future earnings prospects and one that towers over established giants including Toyota, Volkswagen, Ford among others.

Another bubbly note resounds via a Goldman Sachs index of technology sector shares that do not produce profits. This basket has surged by nearly 400 per cent from March, having largely muddled along since its inception in 2014. Green energy funds and baskets of innovative tech company holdings. put together by ARK Investment, the New York investment company, have all experienced a supercharged performance during the past year.

“Speculation thrives when there is an ample amount of credit and investors have an opportunity to buy something that is new and exciting and captures the imagination,” observes Russ Mould, investment director at AJ Bell, the UK retail platform broker.

When the fear of missing out becomes the essential driver of asset prices, eventually the desire to realise vast paper profits prompts a rush for the exit. What crushes a bull market is not the first major pullback. Investors always buy the dip and they certainly did so last March and reaped the benefits.

At some point buying the dip stops working and that fate befell many in the lonely and increasingly frustrating months after the Nasdaq peaked in March of 2000. Investors discover to their cost that market momentum has truly changed from riding the escalator higher with an occasional pause, and becomes a series of juddering elevator descents towards ground level.

Today, someone holds the dubious honour of having bought GameStop at its peak of $483 last week, a stock now trading below $70. Being caught holding the bag does is not only the fate of the frequently derided “dumb money” of retail investors.

Stanley Druckenmiller recounted in 2015 that his worst mistake while managing money for George Soros was to chase internet stocks in March of 2000, after he had sold them earlier that year. Coming back for another flourish scarred Sir Isaac Newton during the South Sea bubble. After making a substantial profit from cashing out early, he was swept back into the mania of the time, only to rue a harsh lesson of financial gravity.

Frustratingly, a bubble only becomes clear in retrospect when it has burst and warnings of excess often arrive on the early side. In 1996, Alan Greenspan, then Federal Reserve chairman described the stock market as experiencing “irrational exuberance”, a warning that frequently invited contempt from bullish investors until the party finally ended in March of 2000.

Before the current pandemic, bubble warnings resounded at each new peak registered by the mighty tech titans, known as the Fangs, a group consisting of Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix and Google. In February 2018, Cathie Wood of Ark Investment set a price target of $4,000 a share for Tesla from a then $300, that prompted ridicule in many quarters. Adjusted for its five-for-one stock split in August, Tesla blew past that target last month. Its share price rally of recent years has confounded hedge funds that frequently sought to bet against the company, while rewarding the true believers.

Changing investor sentiment

When equities plunged last March, many expected a deeper reckoning that would play out for months. A “blink and you will miss it” bear market was followed by a rapid recovery that drove global and US equities to new peaks. This was driven by retail investors and hedge funds, followed by fund managers climbing on board later. There was none of the panic that gripped retail investors in 2008 and resulted in equities not establishing their lows until the following March.

This suggests a new dynamic underpinning investor behaviour. First, technology provides retail investors with plenty of market information and the ability to trade up a storm through online brokerage accounts. Among their ranks are former and current professionals with personal trading accounts.

They are also emulating what Wall Street has long done. Squeezing hedge funds such as Melvin Capital which committed the cardinal error of being stuck in a very crowded trade, has a long history among profession traders.

This brings us to another key point. Courtesy of the pandemic and lockdowns, a powerful combination of record-low interest rates, government support packages and large personal savings rates helps explain a rational decision by many investors to buy equities, particularly the racier names.

With central banks committed to their present policies, not only does it make little sense to keep money in cash or own low-yielding bonds, retail investors sense, rightfully or not, that the equity market downside is limited. Central banks have for years rescued the pillars of the financial system when trouble has struck.

And the growing prominence of retail investors means any big drop in equity values will resonate deeply across the broader economy. Many of us saving for retirement, which forms the backbone of the enormous asset management industry, will feel the claws of a protracted bear market.

“The problem is that the psychological impulse to own something other than cash, regardless of price, has created a situation where stock market valuations have been bid up to levels that imply negative S&P 500 total returns for well over 12 years,” warned John Hussman, president of the Hussman Investment Trust in his latest market commentary.

This places the onus on all investors to observe prudent risk management particularly when markets have been propelled so high on the back of euphoria and cheap money.

“Unless you turn off the monetary taps, speculation will continue rolling through financial assets,” says Mould of AJ Bell. And his counsel for retail investors is: “Never mistake a bull market for brains. We are waiting for the bell to ring that signals a top.”

Comments