The meaning of the F-word — feminism in five voices

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

The unfolding Harvey Weinstein scandal has shone a sharp light on the current state of women’s battle for equality.

Financial Times journalists — men and women — explain what feminism means to them in 2017.

India Ross

FT Weekend journalist

One morning in January this year, I woke up, fumbled for my phone and laid eyes on the feminist event of the decade. From the cold grey streets, a pink woolly-hatted mass appeared on my screen: an expression of female solidarity for the age of Instagram. As I scrolled blearily through the footage of the Women’s March, which was orchestrated on social media, it struck me as being two things at once: a seminal moment in the history of civil rights, and a distinctly millennial sort of protest.

We are at a point in the feminist movement when a once gritty and anonymous grassroots struggle has become “woke”, cool and endlessly Instagrammable. A thankless act of political lobbying has somehow, among the middle-class western youth at least, morphed into a performative, celebratory act of self-expression. Everything we do is pervaded with a sense of sisterhood, of empowerment, of a newfound freedom to be our truest, messiest selves.

On a typical evening a few Fridays ago, for instance, I got home from work, watched an episode of the raucously sex-positive comedy Broad City, put on a scruffy T-shirt that read “Hillary for President”, and went to a queer feminist party called “Pxssy Palace”. It was a sweaty mess of women of all colours, drag queens and non-binary people, all twerking to Beyoncé and Rihanna. There was not a cisgendered, heterosexual man in sight.

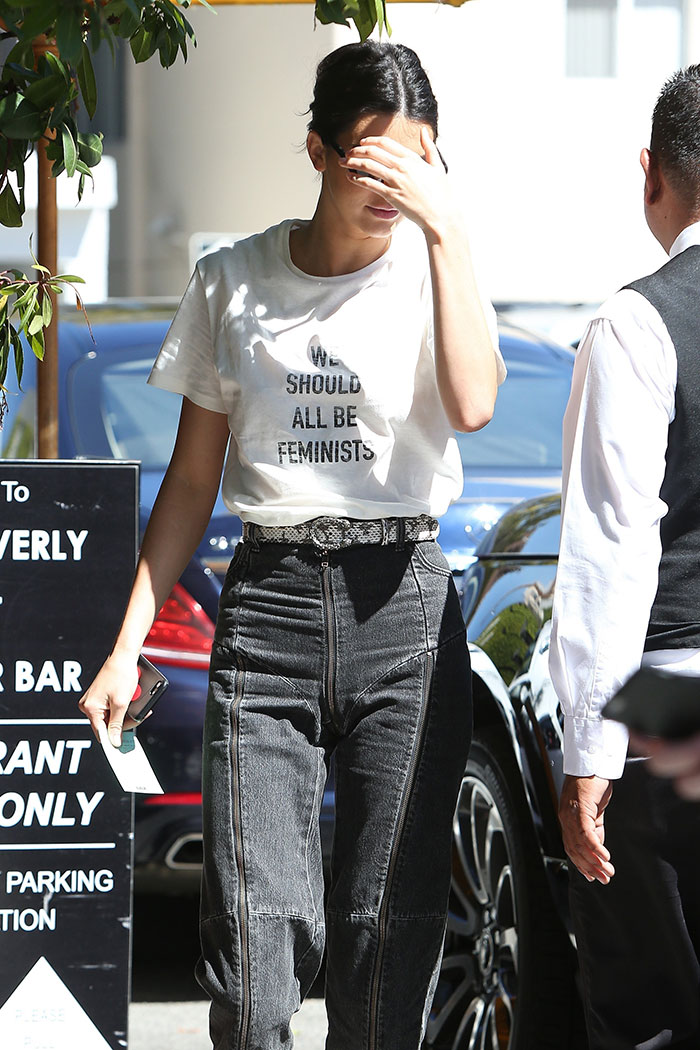

My cohort is more vocal in its fight for women’s rights than perhaps any in history. It’s the generation of “I’m with her”, of Broad City’s signature slogan “Yasss kween”, of Kendall Jenner wearing a £490 Dior T-shirt emblazoned with the words “We should all be feminists”. And yet it is fraught with contradictions. Most of my friends outwardly ally themselves with the cause, but they don’t exactly have a track record of activism.

It seems to me that our involvement is fundamentally thin; we are fair-weather feminists. Well-intentioned, for sure, but ultimately as interested in the movement for the social opportunities it offers, and for the sense of camaraderie and self-worth it lends us, as for its ability to bring about meaningful change. If I were really a feminist, wouldn’t I be volunteering to help women in poverty, or those suffering abuse? Wouldn’t I be lobbying politicians to close the gender pay gap? Wouldn’t I at least have read some Gloria Steinem?

So, all in all, we’re the worst. A generation of slacktivists whose half-hearted approach to civil rights seems unlikely to achieve anything for women whose need is greater than our own. Sure, the fact that my peers now have a more nuanced and open-minded definition of femininity means that I can stop brushing my hair and start wearing tracksuit bottoms to parties, but what we’re doing for those facing more pressing issues than their wardrobes is another matter. Will my listening to Beyoncé’s Lemonade bring about equality for women of colour? Probably not. Will my watching Jill Soloway’s Transparent protect trans women from hate crimes? Unlikely.

But perhaps the Generation-Y brand of feminism isn’t entirely useless. Conversations that begin online and in popular culture can eventually manifest themselves in real-world change. Whether or not this year’s Women’s Marches turn out to have any impact on the future of civil rights is yet to be seen, but these events occurred — and history will remember them. Half a million people left their homes and drew the attention of the world by walking together in the January cold. Even if they were only there for the selfies.

Henry Mance

FT political correspondent

Your thirties are when it becomes real. At least for me — as a man, and as a new father. It’s when feminism starts to require reflection and sacrifices.

Oh sure, I thought I was a feminist in my teens and my twenties. But it was a box-ticking exercise. All I signed up to was to nod at mentions of the Suffragettes, and to frown at jokes about female drivers. I just didn’t want to be a philistine. I read The Vagina Monologues, and I never thought about it again.

I do vaguely remember my wife once saying, “I hope you would call yourself a feminist.” But in practice, the only test was that when she cooked, I washed up, and vice versa.

In my defence, girls beat boys in exams when I was at school. And when I was at university, female students outnumbered males. In the UK, there is virtually no pay gap between men and women in their twenties.

So as a young man starting work, you can recognise that women are worse off, and think that it is another generation’s problem. You can be a male feminist in the belief that the problem is working itself through the system.

For me, this changed soon after I hit 30. Before having kids, my wife and I divided things roughly equally. Our daughter exploded that pretence. I took just two weeks’ paternity leave and went ahead with my career, while my wife put hers on pause. I knew I should have taken more leave. But however ridiculous it sounds, I also felt like the prospect of a career break came a little out of the blue. I hadn’t been given enough warning! This was the cost of not thinking about it in my twenties. I had reproduced the failings of the previous generation.

Nonetheless, inequality at home has made me more alive to inequalities outside. Why are there so few women on TV panel shows? Why do women receive more abuse online? I find it hard to look past these issues. I’m less interested in TV shows and films that fail to develop female characters. In other words, feminism has ruined Woody Allen for me.

But I have found two things particularly difficult. First, feminism isn’t costless for a man. “Every time we liberate a woman, we liberate a man,” the ever-quotable anthropologist Margaret Mead said, and it’s a nice line. But if women are going to occupy more top jobs, that by definition means men will occupy fewer. If women are going to have more power and do less childcare, then men are going to have less power and do more childcare. And if we focus on eliminating the pay gap between men and women, which mainly exists among older employees, will there be less in the pot to close the pay gap between young and old?

The second difficulty is judging what a feminist approach is. When John McEnroe said Serena Williams would be ranked “like 700 in the world” if she were a male tennis player, I thought he was just stating a fact. My wife exposed it as a false comparison — like pitting a middleweight boxer against a heavyweight.

These gendered topics feel like dangerous territory, and the easiest option is to skirt round them. But I feel like men need to be in the conversation. Feminism is a duty you can’t discharge just by silently thinking the right things.

Of course, I haven’t worked out exactly how you can discharge it. I should start by doing 50 per cent of the childcare and domestic tasks, but I haven’t come to terms with some of the sacrifices that would entail. I could also talk about gender with other men, but it is generally uncomfortable. I could confront bias wherever I see it, and I’m not sure why I haven’t done. Indeed, the process of writing this article has driven home the point: there is no excuse.

Brooke Masters

FT companies editor

“Feminism: the radical notion that women are people.” The T-shirt beckoned from the wall of the H&M store and my teenage daughter grabbed it.

She loves it wholeheartedly; I have a more complicated relationship with the women’s movement.

At university in the US, I was outspoken — marching against sexual assault and raging about the complete dearth of tenured female maths professors. In my 20s, feminism receded to background noise. I genuinely felt I had equal opportunity to succeed and my male bosses did much to advance my career. By my 30s I was too busy trying to have it all — career, house, husband, kids — to think much about women’s rights. I cut back to four days a week because exhaustion, rather than discrimination, was my biggest barrier to success.

Then came my forties. My kids went to secondary school, and my supportive boss talked me into going full-time and joining senior management. Surprisingly, I liked the challenge of figuring out how to get the best work out of a diverse group of people with different styles and priorities.

But I also found myself back in the minority, one of only a couple of women around a table full of men.

Where was everyone? If the doors really were wide open, why was I the only one walking through?

The more I thought about it, the more I realised that I had been very fortunate to avoid the hazards that had torpedoed my friends’ and colleagues’ careers. One friend was advised by her doctor to quit her high-powered legal job to increase her chances of successful IVF. Another was denied tenure by an academic department riven with gender tension.

Timing also helped: by the time I found myself stuck sitting near the known newsroom “problem” (not at the FT, I might add), he had recently been disciplined. That meant he was on his best behaviour and the bureau chief was on alert for signs that his fascination with my breast pump never crossed the line from weird to worrisome. And when my husband realised that he would eventually need to do an overseas stint to advance his career, we had enough warning that I was able to change to an employer with a big European presence.

As one of the lucky ones, I decided to go back to being an active feminist. What is the point of rising if you pull the ladder up behind you? When a male colleague used a job interview to question why a younger female reporter would be interested in a “male subject”, I called him out for it.

And when a senior partner at a law firm said to me at a formal dinner that he never promoted women whose husbands had demanding jobs because “they always quit to have babies”, I telephoned the firm to inquire if this really was company policy.

At the same time, it has become very clear to me that overt discrimination is not the biggest barrier to success for most people most of the time. My entire team — both men and women — works hard, but we all struggle to mesh obligations to children and ageing parents with the need to be present in the office.

Feminism in my forties started to be about changing the entire system to make a wider variety of choices possible for everyone. I stopped worrying about whether I fitted in or lived up to society’s ideal for a woman or a worker, and started aiming for a life that worked for me — and I encouraged my team to do the same.

Some of us arrive late after school drop-off, others leave early to check on ailing relatives. I’m sure we collectively miss more conventional working hours than a traditional all-male team would have done, but people put in longer hours when necessary and the work gets finished anyway.

Political activism and speaking out still matters. But to me the battle is now focused on keeping everyone’s options open. New research suggests that subsidised childcare more than pays for itself in improved retention and lower absenteeism. We need more women in boardrooms and tech companies, and more men in primary school classrooms and nursing stations.

So please, let’s bin both the T-shirts that say “the future is female” and those that suggest girls care more about make-up than mathematics.

Jan Dalley

FT arts editor

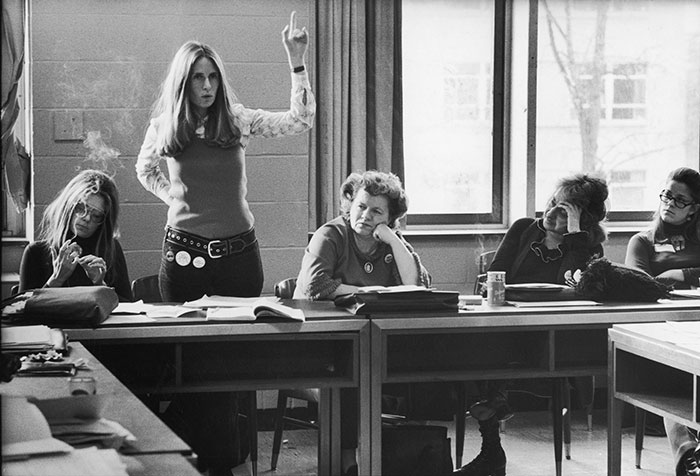

I grew up in a lucky time and place: peace, antibiotics, education ad lib, the pill and the music to use it to. And feminism. By the time I was at university in the 1970s, feminism was already our element, the air we breathed. Earlier generations of women had blazed a trail that we seemed to stroll along. It was no utopia; there was still a huge amount to do and changes to be made — as there still are — but there seemed to be no reason why progress shouldn’t keep on keeping on.

And yet. One sad thing about getting older is that you realise things can move backwards. Feminism’s triumphs, fragile as they often were, should have come with a health warning: beware of what you wish for. In fighting for women’s right to determine their own ways of living, we — perhaps like all campaigners — nevertheless had a pretty firm view of what those choices would be, and should be. To see an obviously educated and uncoerced young woman walking down a western street with her head covered is something that would literally never have occurred to the early feminists: that a woman would make such choices, in freedom, would have been beyond their thinking.

This is just one example of why “feminism”, as a purely western credo born in America of postwar affluence, is no longer particularly relevant, to me or to others. The principle of equality between the sexes is now sturdily enshrined within a general notion of liberal human rights; feminism has done its work there. Meanwhile, though, identity politics has fractured into a kaleidoscope of infinitely shifting pieces, and the old dichotomy, the XXs versus the XYs, seems inadequate.

Feminism has also been unable to shake a bad reputation among young women. Just a couple of years ago a Huffington Post article quoted a range of young stars — the likes of Taylor Swift, Katy Perry, Lady Gaga, Björk — all disowning the label: they associated it with stridency, man-hating and (although they didn’t say so exactly) unsexiness.

It’s true that stridency was the worst aspect of ur-feminism; now, the besetting tone of identity and gender struggles is whining. Poor Me-ism. When Tom Wolfe dubbed the 1970s the Me Decade, he had no idea what was to come in our hyper-individualised Facebook age.

This relates to something that always puzzled me, over the years — call it the Thatcher Effect (because of her abysmal record of encouraging and employing other women) — namely, why do individual women’s achievements seem to have so little to do with the wider feminist cause? Answer: because high achievers, though they might have ridden in the slipstream of earlier campaigners, are essentially individualists. Feminism was and is essentially communitarian. And in that regard, hopelessly 20th-century.

The other conundrum is why feminism often seems to have failed us, when it comes to the practicalities of life. Glaring inequalities still persist in the day-to-day realities, even among people who live in a liberal climate.

In my view, feminism hasn’t failed us; we have just asked it the wrong questions. Feminism never claimed to tell us how to live. There was no blueprint. That housework rota stuck to the fridge was never going to cut it. What feminism did, and continues to do, is to tell us how to think about how to live. And to campaign for the social and legal climate that will allow the greatest possible freedom of choice. After that, each woman has to work it out for herself. Feminism is a state of mind.

John Gapper

FT chief business commentator

The other evening, at a dinner party of people in their fifties (or about to reach them), the TV producer sitting next to me laughed despairingly. “Maybe men are just horrible,” she said. I looked around my fellow males — the head of a think-tank, a physiotherapist — and thought, does she mean us?

Over food cooked by the husband of the host family, we had been discussing Eden, the reality TV show in which the male participants went feral in the wilderness. As talk then turned to the misogynist dystopia of The Handmaid’s Tale, something struck me: the women at the table held an animated, intellectual conversation about modern feminism, while the men listened, nodding occasionally, in respectful silence. It felt like a mirror image of a 1950s dinner party, at which the men might have opined while the women agreed.

Born in 1959, I turned adult in the first post-feminist generation. The initial battle had been fought and, intellectually at least, I took the essential idea as read. Feminism felt like a distant cousin, an accepted presence but not something that I needed to spend time studying.

“That’s outrageous. You know nothing about the subject,” my 16-year-old daughter responded when I told her I was writing this article. True enough. I wasn’t the one with her nose in Simone de Beauvoir’s Memoirs of a Dutiful Daughter on our summer holiday. Yet by osmosis, or through spiky debate over dinner with my female family, I care about it more and more.

When she and her sister were small, we read them The Tiger Who Came to Tea by Judith Kerr, in which, after the thirsty beast departs, Sophie and her mother are taken out to supper by the returning father. I found the image of him drinking half a pint of beer in a cafe with his womenfolk around him comfortingly evocative. These days, nothing about gender is easily settled. My daughter’s class recently discussed a feminist interpretation of Where The Wild Things Are: the domesticated male’s fantasy of fleeing a dominant woman to find fulfilment in tribal rituals etc. Where did that girlish innocence go?

My family shows me things I did not notice enough: that female emancipation is still a struggle; that academic achievement does not always lead to career advancement; that crude forms of discrimination are less socially acceptable, but subtler ones endure.

Secretly, I thank my lucky stars. I climbed the career ladder at a favourable time for a man. Nobody thought too rigorously about gender imbalance, or not hard enough to become a problem for me. Now, as my daughters approach the world of work, things are gradually changing. My gender portfolio has rebalanced at just the right time.

But I also read the news, and see the society of The Handmaid’s Tale being recreated in Syria by Isis, and recoil at Harvey Weinstein’s predatory behaviour. Feminism looked like it was riding the wave of history but tides can retreat as well as advance.

For these reasons, I feel less complacent now. “Feminist Society is for everyone,” read the poster for the sixth-form group that my daughter recently founded, and I found myself agreeing.

Follow @FTLifeArts on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first.

Subscribe to FT Life on YouTube for the latest FT Weekend videos.

Sign up for our Weekend Email here

Photographs: Leonard Mccombe/The Life Picture Collection/Getty

Comments