French election results: Macron’s victory in charts

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Emmanuel Macron, the independent pro-European centrist, emerged victorious from the presidential election against Marine Le Pen of the far-right National Front.

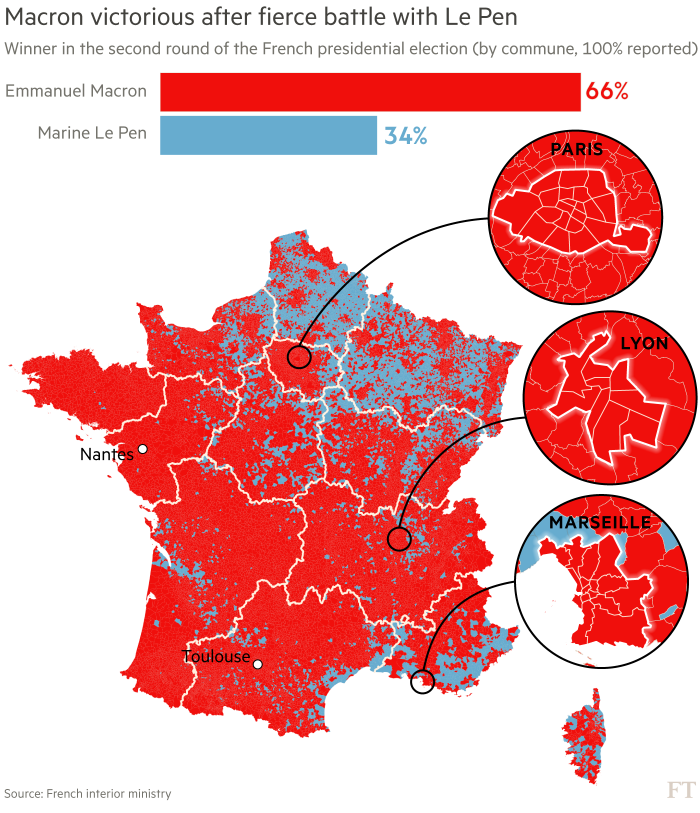

It was an election that split France — and the early maps of voting results give some ideas of the two candidates’ respective heartlands.

Polls of voters who participated in both rounds of voting show how allegiances shifted from the candidates eliminated in the first round to Macron and Le Pen.

Macron made huge gains, picking up the majority of first round supporters of the two leftwing candidates, Jean-Luc Mélenchon and Benoît Hamon. More surprisingly, Macron won almost half of the votes of those who went with centre-right candidate François Fillon in round one.

Le Pen made most of her second round gains from Fillon supporters and also secured around 10 per cent of Mélenchon backers.

As expected, more than one-third of Mélenchon supporters abstained, but this was not enough to hurt the president-elect.

Macron’s victory was welcomed with a sigh of relief in Europe, where many saw it as a litmus test of strength for the populist insurrections around the continent. Where did he draw his support from? Below we analyse factors that might have been at play.

Education

Education seems to be the strongest predictor of the Macron vote: the higher the number of people with a university degree in an area, the stronger the vote for the candidate.

This kind of geography-based analysis can fall foul of the ecological fallacy — just because we know the overall characteristics of an area’s population, we cannot be sure the same attributes apply to those who turned out to vote — but in combination with the results of surveys taken on polling day, this can provide useful insights.

The chart below shows counting areas grouped into deciles of the electorate, ordered from the least to most “educated” across France. The key relationship is between the vote share for Macron (vertical axis) and the level of educational attainment (horizontal axis). The reverse holds true for Le Pen, who gained most votes in areas where the level of education was relatively low.

This pattern echoes the findings of a Financial Times analysis of the predictors of the Leave vote in 2016 Brexit referendum, US presidential election and recent Dutch election. In each of the plebiscites, education emerged as the strongest predictor of vote for a populist option, where the less educated chose it more often than those with degrees.

However, as before, it is important to highlight that education is often a proxy for a set of personal beliefs and circumstances that impact individual’s academic choices and voting preferences.

Income

First-round voting projections and research reported on by the FT indicated that higher income voters were more likely to vote for Macron. This trend reinforces the narrative of the presidential race as a battle of haves versus have-nots, embodied respectively by Macron and Le Pen.

The data bears this out — to an extent. While areas with higher median annual income were more likely to vote disproportionately for the centrist candidate, the effect of income is negated when education is taken into account.

This makes sense — income tends to increase as a function of education level. What is more, people with higher incomes are more likely to live in urban areas, where other social factors come into play.

Like education, income was also a factor in the recent Dutch election, in which less affluent areas voted in proportionately higher numbers for the populist Geert Wilders. This was also true in the UK’s EU referendum, where analysis suggested lower income voters were more likely to vote Leave.

Working class

After education, the percentage of working-class voters in an area was the biggest single predictor of a vote for Ms Le Pen. The category combines manual labourers and low-skilled employees in the services sector.

Working-class voters have become central to Ms Le Pen’s narrative and manual labourers in particular are often seen as having been left behind by the establishment or as victims of globalisation.

However, the FT’s analysis of the result has showed the reality may be more complex. The proportion of working-class voters in an area becomes statistically insignificant when education and age are taken into account.

This is possibly linked to the fact that people with a university education are less likely to work in less-skilled professions, and participation in higher education has increased over recent decades.

We should also note that the blue-collar demographic has a high percentage of immigrants than other employment sectors and such people are less likely to be able to vote.

Unemployment

Like those on a low income, the unemployed have been portrayed by Le Pen as having been left behind by globalisation.

Interestingly, unemployment was a better indicator of a vote for Mélenchon in the first round than it was for Le Pen, and was a better indicator of a vote against Macron in the first round than in the second, indicating a divided electorate that rallied behind Macron.

What is more, unemployment, while being statistically significant across the country, was not associated with the Le Pen vote in urban areas. As the results in Paris, Lyon and — to a lesser extent Marseille — have illustrated, Le Pen has struggled in cities, with their lower income, unemployed voters more likely to vote for Mr Mélenchon in the first round.

Wellbeing and pessimism

Surveys of second-round voters have shown that Le Pen supporters tend to be more pessimistic about the future. They take a much dimmer view of the prospects of the next generation than do those casting ballots for Macron.

Similar findings were described in a study by Luc Rouban, professor at Sciences Po Cevipof. He showed that the perception of being worse-off than your parents contributed more to the propensity to vote Le Pen than an objective state of being so.

Life expectancy

The vote for Macron was higher in regions where people tend to live longer. At first glance, the mechanism behind this relationship may seem unclear, but recent research suggests there is much we can learn from this.

There is a growing school of thought that health metrics, including life expectancy, can be used as precision proxies for imprecise concepts such as wellbeing and pessimism, allowing researchers to identify social breakdown without resorting to large-scale surveys and self-reported measures.

This allows us to interpret the positive relationship between life expectancy and the Macron vote as additional evidence that general wellbeing and a positive outlook on life lead voters to reject Le Pen’s appeals to negative emotions, and vote instead for a candidate with a more positive message.

Immigration

Although the FT’s analysis found no correlation between the number of immigrants in an area and the share of vote for Le Pen, surveys have consistently found that Le Pen’s supporters are likely to view immigration as a key issue. The national debate around the refugee crisis and the terrorist attacks that have shaken France in the past two years has played a key part in the result.

This mirrors the situation in the UK’s EU referendum, where data suggest strong negative attitudes to immigrants were not only a key indicator of a voter’s likelihood to cast a vote for the Leave campaign, but a key indicator of their likelihood of voting at all.

Anti-establishment motivations

As expected, the more left-leaning the voter, the greater the preference for Macron. But there was one exception to this rule: surveys of second-round voters found that a higher share of those self-identifying as having political views on the “far left” backed Le Pen than those identifying as merely “left” or “left-leaning”.

This is in line with the emerging pattern of a realignment of western politics from the traditional left-right spectrum to an ideological battle between the establishment (centre) and the extremes.

Age

Age was a key dividing line in the UK’s EU referendum and the US presidential election, with younger voters overwhelmingly backing Remain and Hillary Clinton respectively, but in France that pattern was turned on its head.

Although it should be noted that Macron won more than 50 per cent of votes in every broad age group, Le Pen fared best with voters aged 35-49, and secured 34 per cent of the vote among 18-24s, narrowly above her total share across all voters. By contrast, she won just 27 per cent of the vote among over-65s.

This reversal of the pattern seen in the UK and US can be explained by two factors: first, young people in France are frustrated at a lack of jobs and poor economic prospects, with some seeing a vote for Le Pen as a vote against the system that has created these conditions.

And second, those same younger voters are less familiar with the openly xenophobic party that was the Front National of the 1970s. The FN’s previous incarnation still leaves a bitter taste for many older generations, who voted accordingly on Sunday.

Macron’s broad appeal vs Le Pen’s narrower support base

Looking at the 500 geographical areas in which Le Pen and Macron each fared best reveals how much the former FN candidate struggled to find favour outside of her base. Areas with very low populations were removed to limit their potential to skew the analysis.

Le Pen’s strongest performances came almost exclusively in areas with low education. Across the whole country, she did not beat Macron in a commune in which more than 39.7 per cent of people had a university degree.

While Macron performed better than Le Pen in communes with higher average incomes, he was also able to win votes in lower income areas. The lowest median income in a commune where Mr Macron won was, perhaps surprisingly, lower than the equivalent figure for Le Pen: €11,761 vs €13,022. No commune with a median income of over €33,106 cast more than 50 per cent of its votes for Ms Le Pen.

A similar pattern emerged with blue-collar workers — a demographic expected to turn out disproportionately for Le Pen. She was only able to win in communes where at least 14.7 per cent of workers hold blue-collar jobs, and fared much better than Macron in communes where large proportions of the labour force are in unskilled roles.

Comments