Alibaba looks to emulate Amazon and unlock potential of the cloud

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

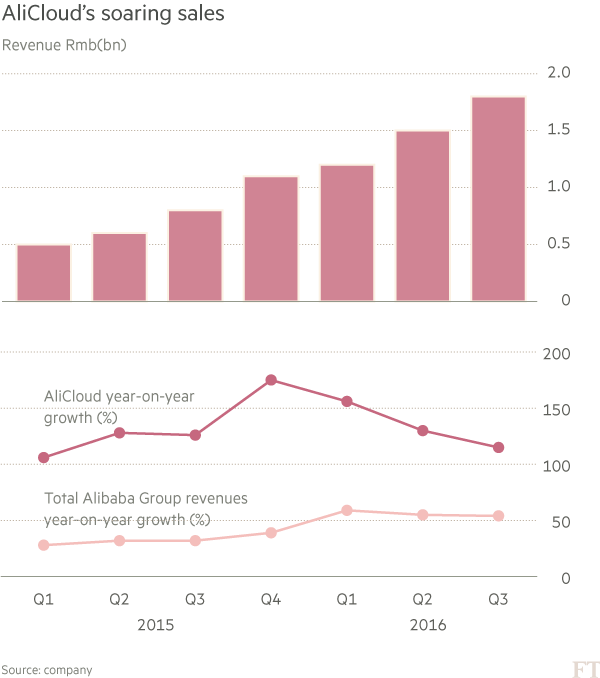

Alibaba provoked an Amazon-style ripple of interest from investors when it reported its quarterly numbers: revenues at AliCloud, its eight-year-old cloud services business, rose 115 per cent year on year to $254m.

The amount may be tiny, at just 3 per cent of the Chinese ecommerce group’s $7.7bn quarterly revenues, but for analysts the parallel was clear. Amazon Web Services, launched in 2006, went from zero to three-quarters of the US ecommerce group’s operating profit over the next decade. AWS, with $11bn of sales last year, is the world’s biggest cloud business.

Underlining the role of, and money in, cloud services in the US is Snap. The owner of messaging app Snapchat will spend $2bn with Google Cloud during the next five years and is reliant on the search company’s infrastructure for “the vast majority of [its] computing, storage, bandwidth and other services”, according to its IPO filing.

China is trailing, but growing rapidly: total spending on public cloud services is forecast to rise from $11.2bn in 2016 to $14.2bn this year, according to Gartner, the research company — a tenth of the $141bn expected to be spent in the US in 2017.

Services, too, have evolved, from data storage into what Alibaba chief scientist Jingren Zhou calls a “highly centralised information management system”, handling everything from staff payroll to security.

“The potential for Alibaba on cloud is the same as AWS,” says Elinor Leung, who heads Asia internet research at CLSA. “It’s about scale and technology. The bigger you are, the less costs you pass on to the customer. You basically kill all the little guys.”

Killing the small fry can be expensive, as Alibaba, and AWS before it, knows. According to Ms Leung, AWS has cut the prices it charges a total of 52 times since its launch, and its rates are now half those charged by smaller competitors,leaving it and Microsoft dominant in the field of IT storage and services.

Likewise, Alibaba halved its core product prices in October. In the latest quarter, it lost $5 for every $100 of revenues generated. And exponential growth does not last for ever — Amazon’s AWS sales growth decelerated, to 47 per cent in its latest quarter.

That does little to damp bullish spirits. “Cloud is a huge deal,” says Marin Ivezic, partner at PwC in Hong Kong, pointing to the interdependency between “big data” and cloud computing.

As more data are generated outside the office or home — from sensors, for example, or the internet of things — so the demand for cloud hosting will grow, he adds. “The value is in the ability to analyse data generated by devices.”

However, the earlier incarnations of the cloud as one big global repository are morphing into more localised centres, partly to meet regulatory requirements and partly because of different demands.

Ethan Sicheng Yu, general manager of Alibaba Cloud’s overseas business, explains: “Our goal is maybe in a few years to establish noticeable market share and to learn local market requirements, because we firmly believe globalisation does not mean you standardise your products everywhere.”

Robert Xu, chairman at Kingdee in Shenzhen, an early adopter of cloud technology and now provider of cloud-based services to hundreds of millions of small and medium sized enterprises, concurs.

“Big data used to be idle in the old era,” he says. “But since we moved to cloud services in the past two years, we have been able to use it in better ways and provide more value to customers.” Those ways include better targeted marketing and using financial data to help secure loans, a perennial problem for SMEs in China.

SMEs provide fertile ground for providers of cloud services in other ways. Mr Xu refers to a “megatrend” driven by both the natural IT renewal cycle (which this time will see businesses move from local servers to the cloud) and China’s changing economy.

“The economy is transforming rapidly in China and companies need to maintain their advantage in better management and better efficiency,” he says. “This is a natural way for them to better survive in the new economy.”

Like the international cloud titans, Kingdee is also looking to bring artificial intelligence to bear in the sphere of big data analytics and other SME services, including alerting them when budget ceilings are about to be hit.

But SMEs are not the only customers. China also boasts a digital generation that has never used a PC or downloaded files to a USB or hard drive, says Chris Ip, a senior partner at McKinsey’s Asia-Pacific digital practice.

“Consumers are leading digital lifestyles. Everyone has a collection of photos, social media history and hoard of electronic files on record. Bank statements and emails — they need to be stored as well.”

Using consumer data generated in China also has the advantage of being cleaner — there is less multiple phone ownership — than is the case in other countries, says Mr Ip, which means marketing and other campaigns are better targeted. Mobile phones have to be registered, and about 99 per cent of Sim cards are linked to national IDs.

“Digital companies are desperate to attract consumers, but also to engage them,” he says. “If you provide that in a way that is subsidised or free, that’s a killer app that encourages people to come back to your platform rather than someone else’s platform.”

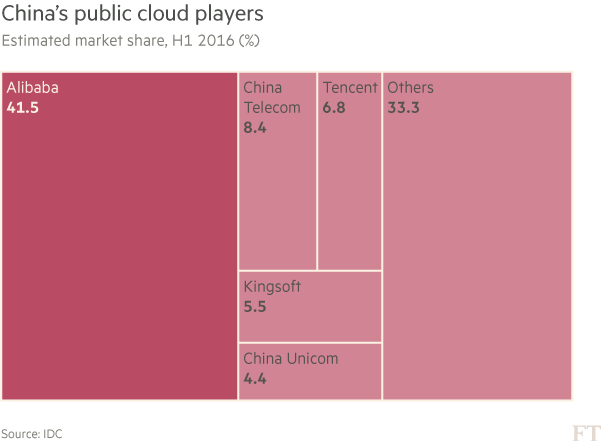

Hence Alibaba’s rivals Baidu and Tencent (together the trio make up China’s internet trinity collectively known as BAT) all offer cloud services. Other China providers include Huawei and China Telecom.

AWS is present through a joint venture with Beijing Sinnet Technology, which owns and operates the data centres, while Microsoft Azure offers services that are operated by 21Vianet. Tencent, China’s third-biggest vendor according to the IDC consultancy, works with partners to operate centres in Asia, the Americas and Europe.

Chinese players are also developing facilities offshore. The consultancy Bain & Co notes in a report, pointing to some of these facilities — including AliCloud’s US data centres — that these “indicate that they may be looking at the market with globalisation in mind”.

Alibaba, says Ms Leung, wants to join its more established multinational peers as part of the “3A” (Alibaba, AWS, Azure) group. But, for all the drivers, she cautions that the jury is out as to its success. “It wants to be top three. Currently people have doubts about China’s cloud.”

Mr Yu has no such qualms. The race between the 3As, he says, has just started. “I think the market is out there. It’s for us to lose. It’s really technology that will differentiate the final winner and I think we have a long way to go.”

Comments