The ups and downs of lifts: how they helped transform our cities

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Heaven and hell. Above and below. It is no coincidence that the continuously moving elevator was called a paternoster. The lift is the strangest room in our buildings. It embodies two of our deepest neuroses — claustrophobia and acrophobia — and compounds them with the unease of being squeezed in proximity to perfect strangers, an unnatural invasion of our private space. Perhaps precisely to counter the primal fears they ought to embody, they have been made into boxes of boredom, neutered architectural non-spaces which are merely an interval between departure and arrival.

Early residential lifts looked very different. In the 19th century “ascending rooms” were conceived as mobile lobbies. The most lavish boasted upholstered sofas, gilt-framed mirrors, Persian rugs, even chandeliers and aspidistras in ornate pots, all accompanied by a uniformed operator.

By the early 20th century, however, the tall building had been taken over by corporate interests. The classic skyscrapers of New York and Chicago were buildings of business, and the lift took on a more commercial aesthetic, more functional, more neutral. And that, more or less, is how they have stayed. Bland, blind boxes intended to allay our nervousness with sheer boredom. Yet while the world’s tallest buildings in the 20th century were offices, the new generation of skyscrapers, from Vancouver to Beijing via London, are all at least partly residential.

The lift has, in theory at least, become a domestic space again — or perhaps, more realistically, some kind of hybrid situated between public space, lobby, security gate and commuter transport. When we think of commuting, we don’t think about the vertical journey, but if you live on the 50th floor, it might be a significant journey every time you leave home, and one where potential speed is limited by the problem of rapidly changing pressure damaging our ears.

Somehow, lift cars themselves haven’t caught up with high-end living. We have taken the technology that underlies the viability of tall buildings for granted. We don’t think twice before getting into an enclosed steel box suspended on steel cables in a concrete shaft. Yet without that technology there would be no tall buildings. In fact, it is lifts that limit the ambition of skyscrapers.

Structurally, there is now very little reason why buildings couldn’t rise indefinitely — the mile-high skyscraper dreamt of by Frank Lloyd Wright (The Illinois, 1957) could easily become a reality. Partly, what has held these designs back has been, surprisingly, lift cables. The physics is such that, after 500 metres in height, the steel lift cables holding up the cars become simply too heavy to support their own weight. However, an innovation from the Finnish manufacturer Kone, in the form of a carbon fibre cable (UltraRope), may change the equation, allowing almost limitless height in a single journey.

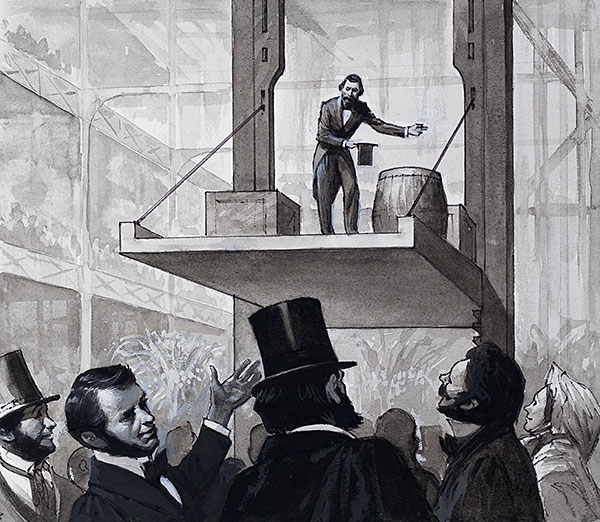

The evolution of the elevator is a parallel narrative of architecture, a vertical section through history, but it is one that begins not in height, but in depth. The origins of the lift are in the theatre and the mines — in both stage effect and pure engineering function. The Romans used lifts to transport gladiators up to the floor of the arena and for creating special effects in the theatre. In 1854 Elisha Otis, founder of the elevator company that bears his name, also used theatrics to demonstrate the effectiveness of his new lift. To show his safety mechanism at New York’s version of the Crystal Palace, he cut the cables on the platform while he was standing on it, elevated above the crowds. That was the crowd-pleasing moment that led to lifts being brought up from the mineral mines and into city skylines.

The explosion in skyscrapers from the end of the 19th century to the modern day is the direct result of Otis’s showmanship. And those towers really are still for display; even cities in the desert, where there is no need to go high, demand a skyline as a validation of their projected economic power. The residences in those high-rises impart to their owners a sense of untouchability, of living in the clouds away from the crowds in the street. Height separates. Except of course, in cities such as Hong Kong and São Paulo, where height has become the norm — where an unusual condition occurs of something akin to vertical streets between the buildings, with the neighbours opposite always a part of the scenery.

There have been some changes in elevator aesthetics that have attempted to respond to our increasing reliance on vertical transport. Most impressive were the innovations of John Portman, who pioneered the atrium building in the 1960s and 1970s and designed glass lifts as a kind of dynamic sculpture to animate the huge interiors. There was something of Willy Wonka’s glass elevator in these panoramic capsules, a sense that they might just carry on beyond the confines of the structure. Richard Rogers took the genre a little further, with the elevators on the outside of London’s Lloyd’s Building and later with glass lift shafts at One Hyde Park. One step weirder is the lift at Berlin’s Radisson Blu hotel, which rises through a cylindrical aquarium.

Perhaps the most striking architectural fashion of the moment, however, is not for people at all, but for cars. An “en-suite sky garage” is the new must-have for owners of supercars. No more underground parking for these oligarchs; instead, just ride up in your car to your apartment and look out on your prized possession all day.

It is a very curious device — a framing mechanism that sees the city as background for the car. Pioneering examples can be seen at 200 11th Avenue in New York (Selldorf Architects) and Hamilton Scotts in Singapore, ironically both in cities where cars are virtually unnecessary. Instead, the auto becomes an exhibit, lurking in its glass vitrine.

What these sky elevators do is to begin to celebrate the usually invisible technology. Transparency might not do much for those with a fear of heights but a view might reduce some of the odd effects of lift travel. We are uneasy in lifts, unsure of how to interact with others. Researchers have found that there is an instinctive way of arranging ourselves inside a lift. The first person stands in the middle. The arrival of a second means they arrange themselves to either side. When two more arrive, the passengers move to the four corners, always attempting to keep maximum distance between bodies.

It may be that enforced intimacy that makes the lift such a popular setting for movies, for romantic serendipity and farcical intimacy. From the first falling in love in The Apartment to the sinister ascent in Barton Fink and the claustrophobic schlock horror of Devil, the confinement of the car stands in for a particular kind of intensity. Yet it is expressed in the bland non-architecture of the least memorable room, a frustrating neutrality amplified by annoying touches such as elevator music and door-close buttons that don’t actually do anything. In fact, the computerisation of lifts and the predetermining of floors, so that there are no buttons to push, may actually be adding to our nervousness at the increasing lack of control — the illusion of which was always an important part of the design.

When I moved into my old mansion block I wondered how the dimensions of the tiny lift with trellis gate doors were determined. The lift, I was told, originally needed to be just big enough to accommodate an upright piano or a coffin. Which sounds about right. Heaven and hell.

Edwin Heathcote is the FT’s architecture and design critic

Photographs: Bob Krist/Getty Images; Ed Norton/Getty Images; Bridgemanimages.com; Alamy; Walter Sanders/Getty Images

Comments