Deutsche Bank: problems of scale

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

It was the defining bet of Anshu Jain’s reign at Deutsche Bank. In 2014, as most European banks were retrenching in the face of slackening markets and tightening regulation, the German lender’s then co-chief executive took the opposite course.

Two weeks after Barclays — Deutsche’s European arch-rival — capitulated to market pressure and slashed its debt trading business, Deutsche launched a plan to raise €8bn in capital . The move was, in part, designed to give Germany’s biggest bank the firepower to win market share as its rivals faltered, and to position it as the last remaining European challenger to the US titans on Wall Street. Deutsche, Mr Jain said at the time, would be the “only truly universal bank based in Europe”.

That bet failed: markets remained slack and regulation kept tightening. Two years on, Mr Jain and Jürgen Fitschen, with whom he shared the top job, have stepped down. Deutsche’s investment bank has lost its top three ranking. The group’s capital position is under scrutiny. And Mr Jain’s successor, the former UBS banker John Cryan, has embarked on a painful curtailing of Deutsche’s global ambitions.

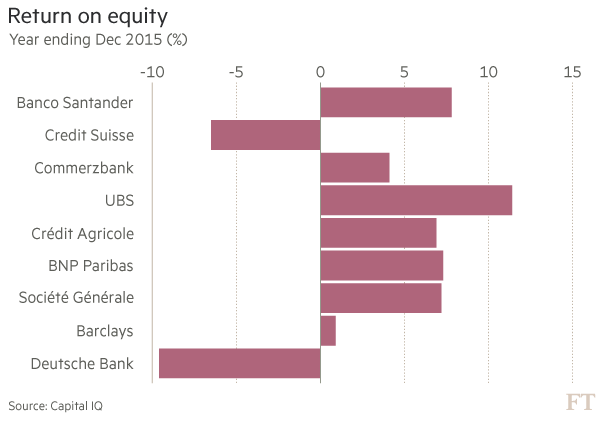

Mr Cryan faces a formidable task. Deutsche’s markets business, which accounts for a third of its revenues, is struggling to cope with a world of lower trading volumes, tougher capital requirements and increasing US dominance. Its retail bank in Germany, where margins were always thin, is suffering under Europe’s rock-bottom interest rates. Total costs are stubbornly high and the bank is grappling with legal challenges that could cost it billions of euros. Last year, Deutsche — a pillar of Germany’s postwar economic strength, and a cog in global capital markets — made a €6.8bn loss amid a host of fines and writedowns. Analysts predict an €860m loss this year.

“The problem for John Cryan is that there are so many moving parts,” says Chris Wheeler, an analyst at Atlantic Equities. “Markets have been very tough this year. Brexit has made things worse. It’s constantly one step forwards, two steps back. He was probably hoping for one-and-a-quarter steps forwards, one step back.”

Investors are so concerned about Germany’s biggest bank that earlier this month its share price fell to €11.22 — a level not seen since the 1980s, and 24 per cent lower than at the depths of the financial crisis. Deutsche is not alone, bearish sentiment has afflicted its rivals, too. After the UK’s shock decision to leave the EU, bank shares across the continent fell sharply. But Deutsche has become the bogeyman among global banks.

At Thursday’s close, investors were implying that the biggest bank in Europe’s most stable economy is worth €17.7bn, just a quarter of the book value. Its travails have turned it into a political football with Matteo Renzi, Italy’s prime minister — who is keen to deflect attention from his country’s banking problems — taking a swipe at Deutsche’s gargantuan derivatives book last month.

When the details of the latest round of European banking stress tests are published later on Friday, Deutsche’s results, along with those of Italy’s institutions, will be closely scrutinised. Analysts fear that Deutsche will fare poorly, partly because, for the first time, the tests will take conduct risks — Deutsche’s Achilles heel — into account.

If the result matches the worst-case expectations, the bank could be pressed to raise capital. Even if its numbers are better than feared, as long as improved returns are elusive there will be questions over whether Mr Cryan’s strategy is right — and if not, what else the bank should do.

Looking for a pivot

When UBS was looking for ways to improve its fortunes in 2012, the Swiss bank chose to make big cuts to its investment banking arm, a move that has helped it boost profits and capital. But UBS had the luxury of pivoting towards wealth management, another strong franchise. Deutsche is dominated by its investment bank and has no other businesses with the scale or profitability around which to regroup.

“Because retail banking in Germany is so tough, Deutsche doesn’t have a strong home market to fall back on like Santander does in Spain, or BNP in France, or UBS in Switzerland,” says a senior German banker.

The cornerstone of Deutsche’s plan is its decision to offload its Postbank retail business, which analysts estimate is on the bank’s books for around €5bn. The group will also reduce assets in its investment bank and cut costs by laying off 9,000 of its roughly 100,000 staff, closing operations in 10 countries from Argentina to New Zealand and shutting bank branches in Germany. If the plan works, Deutsche hopes to see a significant boost in its capital position and profitability by 2018.

It has been hard going. The bank made a €700m pre-tax loss in the final three months of last year, even excluding restructuring costs. Profits in the first quarter of 2016 were less than half the level of a year earlier while in the second quarter they all but vanished.

Deutsche’s senior managers have always warned that the costs of the overhaul would be felt a long time before the fruits appeared, and that 2016 would be the year in which restructuring charges peaked. It has also been hit by sluggish markets, which have pushed down returns across the investment banking industry. Brexit has added to the uncertainty, putting a dampener on Deutsche’s trading and advisory businesses, while the downward pressure on European interest rates has intensified the strain on the bank’s retail operation.

With the share price slumping, questions over whether its strategy needs adjustment are becoming more intense. One concern is whether Deutsche will be able to sell Postbank as planned. No buyer is in sight and the market for European listings is comatose.

Marcus Schenck, Deutsche’s chief financial officer, said on Wednesday that the bank was not under pressure to offload the unit in 2017 but, without a sale, a key part of the plan to bolster capital would have to be rethought.

Cutting out risk

The other area of focus is the investment bank. Regulation has had a huge effect on the business, with tough capital rules already prompting the bank to withdraw from activities such as high-risk weighted securitised trading and flow credit.

Deutsche’s plan for the investment bank by 2018 includes reducing client numbers by half and cutting risk-weighted assets by a net €28bn. These actions are, however, far less sweeping than those of its European rivals, such as UBS and Credit Suisse, the latter of which is cutting almost $60bn of risk-weighted assets from its investment bank and coming under pressure from investors to do more.

With even tighter rules to come, many observers think Deutsche will have to cut assets in its global markets business more sharply. “This is where Deutsche Bank’s structural problem is,” says Daniele Brupbacher, an analyst at UBS. “It has this business with huge leverage exposure, which is not earning enough money.”

Others disagree. “The problem for Deutsche is that it has got to the stage where if it continues to cut assets, it is going to lose a significant amount of revenues,” says one of the bank’s top 20 investors.

Kian Abouhossein, an analyst at JPMorgan, is also sceptical about the chance of a dramatic shift in approach. “Deutsche Bank is an investment bank, so from that perspective to change strategy is not possible; to do what we would like Credit Suisse to do [is not possible],” he says.

Deutsche also faces the consequences of a history of weak controls. It is facing 7,000 separate lawsuits and regulatory actions. At the front of investors’ minds are a US inquiry into the mis-selling of mortgage-backed securities, and a joint US-UK probe into $10bn of potentially suspicious trades involving Deutsche’s Russian business.

Mr Cryan has said he wants to resolve Deutsche’s big cases as soon as possible, and the bank disclosed on Wednesday that it was in settlement talks with the US Department of Justice over the mortgage probe. What concerns investors, however, is that they have no idea what the settlements will cost and, in particular, whether it will be more than the €5.5bn Deutsche already has in litigation reserves.

A shortage of capital

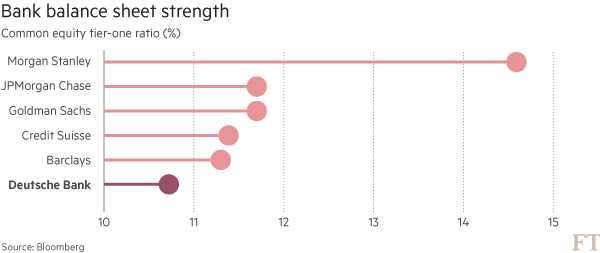

The conclusion that many analysts draw from this combination of weak earnings, high restructuring costs, tightening regulation and looming legal risks is that Deutsche needs more capital. The bank’s management has repeatedly said it has no plans to issue new shares. But its core tier one ratio — a key measure of financial strength — stood at 10.8 per cent at the end of June.

The ratio will get a boost later this year from the sale of a stake in a Chinese bank. But it is low in comparison with its peers and analysts reckon Deutsche is about €7bn short of its target of 12.5 per cent by 2018.

A person close to the senior management says there is no sense in raising capital before the bank resolves its larger US litigation cases. Otherwise it will end up paying much of it out in settlement costs. “In the short term, I can see that they don’t want to raise capital before they have settled in the US,” says the top 20 investor. “But it is clear that in the medium term, Deutsche needs more capital.”

The problem for the bank is that it has too few options to improve its capital position. Given its weak profitability, some people close to the company acknowledge that the least painful way to improve its position, retaining profits, is unlikely to close the gap.

Cutting assets further would improve ratios but at the expense of longer-term earnings. Selling businesses, such as its asset management arm, have similar disadvantages. With its shares well below book value, and bank stocks hardly in vogue with investors, it is also not a good time to go to the market to raise equity.

With such limited options, there is even chatter among bankers that the state might have to stand behind a rights issue, something German officials dismiss as speculation by hedge funds keen to drive down Deutsche’s share price.

It is not only speculators raising concerns. The jitters are a sign of Deutsche’s significance as the biggest bank in the most important economy in Europe, and a reminder of how high the stakes are, not just for Mr Cryan. The International Monetary Fund said last month that, among globally significant banks, Deutsche “appears to be the most important net contributor to systemic risks”. No one wants the fund to be proved right.

Comments