David Rockefeller Jr: ‘Does happiness come from material wealth?’

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

“Mr Rockefeller has just taken his seat,” the woman at The Modern’s front desk tells me, but when I arrive at the table, it is empty. As I look around for the great-grandson of the man thought to be America’s first billionaire, I notice only five tables are full.

It is a few minutes before a figure appears at my shoulder. David Rockefeller Jr had moved to a corner table, thinking it would be quieter. It could not be much quieter, but discretion has become a family trait. This is home turf for the 76-year-old: the names of his relatives dominate the list of Museum of Modern Art donors on a nearby wall, and their imprint on Manhattan is visible from the courtyard outside, where John D Rockefeller’s mansion stood before trustbusters broke up Standard Oil, to the Art Deco Rockefeller Center a few blocks away.

New York, he explains is “our place of culture, our place of spirit, our place of art, our place of business”. It is, I reflect, a rather lofty way to describe the heart of what was one of the most ruthless business empires in US history, but captures how the Rockefellers have successfully shifted their image from corporate buccaneers to pillars of the establishment. “I think my great-grandfather and my grandfather were horrified by the extent of public criticism of, and in some cases hatred of, the family more than 100 years ago,” he says later, but “I don’t run into a lot of people who seem to genuinely hate me or my family.”

A century of philanthropy has probably helped.

An impeccably suited server arrives to take our order. The menu, which earned the chef two Michelin stars, states that lunch is $138 for three courses or $178 for six (the chestnut raviolo with black truffles is an additional $40). Rockefeller is not sure he will manage even three courses, so orders just two for now: seared scallops and a pork tenderloin. I choose the foie gras to start and chicken poached in champagne to follow. He orders tomato juice, passing up my suggestion of wine. I remember only later that John D Rockefeller was a teetotaller, and order a glass of white to accompany my chicken.

Few families offer a better perspective on the cycles of envy and fascination that mark America’s relationship with its richest individuals. As the FT wrote in a 1937 obituary, David Jr’s great-grandfather went from “the most execrated man in the United States” to one of the most venerated as he steered his fortune to philanthropy. The son of an elixir-selling travelling salesman built an empire that spanned railroads, banks and 90 per cent of America’s refineries before the US Supreme Court broke it up in 1911. Even after spending half his life distributing his fortune, John D Rockefeller was said at his death to control 1.5 per cent of the country’s economic output.

The old robber baron might recognise a few things in Donald Trump’s America, a new gilded age where plutocracy and populism drive politics, rich men’s charities take on the social issues of the day and Washington is struggling once more to catch up with the monopolistic tendencies of the biggest corporations.

But in 2018, with the founder’s wealth spread around philanthropies and descendants, being as rich as Rockefeller doesn’t mean what it once did. The family is in no danger of falling out of the top 0.001 per cent, but David Sr ranked only 581st on Forbes’ 2017 ranking of billionaires before his death last year at 101. As the new patriarch of a clan that now counts more than 280, David Jr is now the face of the family’s fortunes.

Rockefeller does not act like someone who craves titan status. At 76 he is still known as Junior. Was it hard to establish himself as something other than a son, a grandson or a great-grandson? “I think as a boy [the Rockefeller name] was much harder to have because you haven’t established your own pathway,” he says. Despite family pressure to go into business or the law, he started his career focusing on music, as assistant manager of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, and journalism (in 1975 he helped buy a counter-culture Boston weekly called The Real Paper; it was, he said at the time, determined “to take courageous stands on issues, even if it means that higher political and economic forces may try to shut us down”).

Before entering the family business, he explains, “I spent 20 years clarifying who I was philosophically, artistically and in terms of my competencies as a manager and chairman.”

Rockefeller’s first memory of the museum is of childhood visits to the sculpture garden with his grandmother, Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, the MoMA co-founder for whom it is named. “Uncle Nelson”, Gerald Ford’s vice-president, used to send young David books about the collection each Christmas, which he devoured. Now, Rockefeller is a museum trustee, and overseeing his parents’ last and biggest bequest to it.

David Sr was one of the first signatories of the Giving Pledge, the initiative led by Warren Buffett and Bill and Melinda Gates that has persuaded billionaires from investor Bill Ackman to Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg to give away at least half of their wealth. The former Chase chairman had given away about $900m before he died. Most of the remaining fortune (calculated at $3.3bn by Forbes) was in family trusts of which he was a beneficiary but not an owner. His heirs inherit that income stream, but his will stipulated that an estimated $700m worth of art, property and other items he and his wife Peggy accumulated (including his 150,000 beetle specimens) should be sold to benefit groups ranging from Harvard to the Council on Foreign Relations. A dozen works were set aside for MoMA, on top of which it can expect a bequest of at least $125m.

Exactly how much cash it receives will be determined in May. Rockefeller shares Christie’s hopes that its auction of more than 2,000 items will smash the $484m record for a collection set in 2009 by works amassed by Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé. “Given what the Leonardo just did,” he says, referring to the $450m the “Salvator Mundi” fetched last year, “who knows?” Certainly Christie’s is pulling out all the stops to ensure the sale is a blockbuster. Highlights of the collection toured Hong Kong in November and arrive in London on February 21 before rolling on to Los Angeles, Beijing and New York, where lots as diverse as decoy ducks and Napoleon’s sugar bowl now wait, tagged in a warehouse. Rockefeller has been part of the marketing campaign, courting bidders from China to the Middle East.

His name still opens doors, in part because carefully constructed trusts and professional advisers have saved the family from the usual “shirtsleeves to shirtsleeves in three generations” fate. Rockefeller, who chairs groups managing money for relatives he calls “the clients”, has played a part in that. Last year, Rockefeller Financial Services, launched as a family office in 1882, paired with Greg Fleming, Morgan Stanley’s former head of wealth management, in a bid for greater growth. It was Rockefeller’s job to explain the deal to his family and the outside funds and foundations that now account for most of its assets.

At least 100 family members gather twice a year to discuss their investments and charitable giving, he tells me: once at Christmas and once at the summer solstice. The solstice? How Druidical do things get, I ask. “The family’s not that Druidical, but I love the solstice. As a sailor I’m very in tune with where the sun is,” he replies. “Not only at sea,” he trails off, looking out to check where the reflections are bouncing off the skyscrapers.

A waiter pours celery butter soup into white handleless cups, decorating the amuse-bouches with artful swirls of green olive oil. They come with tiny tartlets, filled with something warm, whipped and cheddary, and topped with petals of thin-sliced celery root. Three spoonfuls and two bites and they are gone.

The ModernMuseum of Modern Art, 9 W 53rd St, New York

Tomato juice $7

Glass Carneros Chardonnay $25

Seared scallops with yuzu juice

Foie gras poached in duck broth

Herb roasted pork tenderloin

Chicken poached in champagne

Three-course lunch $276

Macchiato $7

Coffee $6

Total (inc tax) $349.49

“My parents really thought about the art of seeing. They thought about it in relation to flowers, to art, to nature in general,” Rockefeller tells me. I wonder for a moment whether one could say that about any bank chief executive today, before he explains how his own eye developed: “I was a fairly quiet person when I was young, so I did a lot of listening and a lot of looking. I was trying to understand what the adults were about, so I was trained by paying attention.”

His tastes are eclectic, he says, ranging from Old Masters to works inspired by travels with Susan, his third wife. David Sr’s will let each of his children choose up to $1m worth of the collection before it went to Christie’s, and Rockefeller says he surprised himself by falling for some porcelain he found in a basement. Three family homes were put up for sale on his father’s death (his mother died in 1996), but Rockefeller decided to buy a fourth, a farmhouse in the Hudson Valley, complete with its “much more informal” contents. (“Mexican dinnerware,” he explains.)

Our first courses arrive, on Modernist dinnerware. My seared foie gras slices come with pickled mushrooms over which a duck broth is poured. They are salty, but silky. Rockefeller’s scallops, served with yuzu juice and toasted pistachios, look equally appetising.

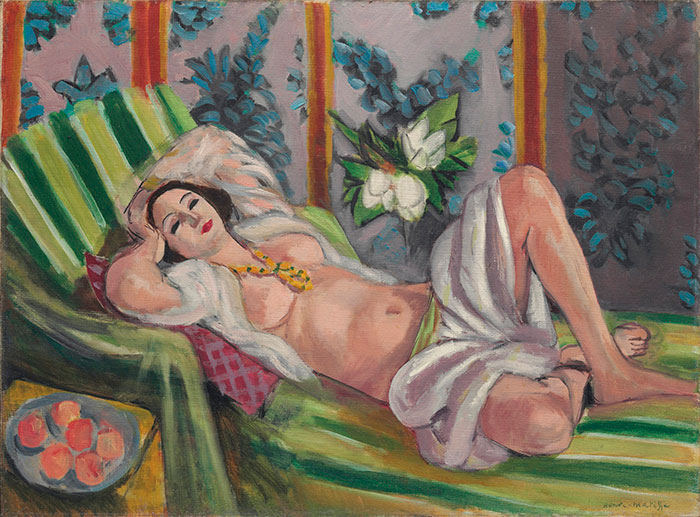

Rockefeller did not grow up with all the art that is going under the hammer — he left for boarding school at 14, just as his parents were getting serious about collecting — but he is sad to see some of them go. “I will miss the Matisse ‘Odalisque’ more than anything else,” he says. The reclining nude would break records for the artist if it fetches the estimated $50m. An unnerving young nude by Picasso, with a basket of flowers and a challenging stare, “is not as much to my taste but just a strong, strong piece”, Rockefeller says. That one, acquired from Gertrude Stein’s collection, may fetch $70m. A former singer, Rockefeller plans to be at Christie’s Rockefeller Center saleroom to watch Jussi Pylkkänen, the star auctioneer who will sell some of the biggest works, because “I’m interested in performances”.

Our second course arrives, with my $25 Carneros Chardonnay, and we discuss his own philanthropy. A competitive yachtsman who got his first boat at 13, he now campaigns for ocean conservation. As he elaborates on the threats to the world’s seas, I remark that I’m glad I didn’t order the lobster. “Lobster would have been all right, actually,” he says, noting that as waters warm around the Long Island Sound the creatures are moving north. “If I were Canadian I’d be investing more in lobster,” he says. I take a bite of chicken (again, the salt is coming on strong).

Rockefeller’s efforts to save the oceans have run into an unsympathetic Washington since Donald Trump’s election. “Unfortunately a minority in the country discovered how to manipulate public opinion” by sowing doubt about science, he says, and as this administration prioritises offshore oil and gas extraction, “we have a fight on our hands to get the right balance”.

It is, he acknowledges, an unexpected critique to hear from the scion of an energy empire. The family fund announced in 2016 it would divest from its petrochemicals holdings. Some accused them of biting the hand that fed them, Rockefeller tells me, but the shock value of people with his surname disavowing an industry he now likens to Big Tobacco was useful for drawing attention to the cause. “My family has been financed on the back of petrochemicals, but I say to people my great-grandfather was a smart man and very interested in science . . . He’d be in the solar business today.”

His uncle Nelson was the prototypical Rockefeller Republican, representing a moderate, establishment wing of the party that is all but extinct now. Measured and reasonable, Rockefeller has no appetite for political life but identifies as a Democrat, even as he says the party still has much to learn from its 2016 loss. “I believe the people who voted for Donald Trump will see, not that their reasons for dissatisfaction were inappropriate but that the solution was not in the Trump administration,” he tells me. “I’d love it if we could create Rockefeller Democrats who’d be close to the centre, who’d believe in the importance of government and the importance of business and the importance of the NGO sector working together.”

With his resources, he could push the party in that direction, but is more money really what American politics needs, I ask. “It’s not,” he replies. “It’s too powerful and it distorts what the country should be about in a terrible way, I think, but, having said that, I think until both sides lay down their money swords you’ll have to fund your beliefs with money for the candidates.”

He is still unsure who those “moderate, credible, public-spirited” candidates might be, though. He knows Oprah Winfrey, the billionaire chief executive, actor, television host and rumoured presidential hopeful, but says he would prefer someone with government experience. “You don’t get to become a political leader in China unless you go through the training,” he observes.

A waiter removes our plates. Mine is clean but Rockefeller’s two squat cylinders of pork were more than he needed. Dessert is included but I follow him in opting for coffee instead. Rockefeller has not mentioned the role inequality played in voters’ dissatisfaction with political incumbents, I note, but seems unworried by today’s scrutiny of his class. As bigger fortunes have sprung up from Wall Street to Silicon Valley, “maybe we have some cover”, he suggests. When I ask whether David Jr will also sign the billionaires’ Giving Pledge, he replies with a small smile: “I don’t think I fall into that category.”

The bill arrives. The Modern, like other branches of Danny Meyer’s empire, is a non-tipping restaurant. Apparently it is also a non-discounting-if-you-didn’t-eat-the-set-menu-dessert restaurant. I pay the $349.49 and head for a preview of his parents’ collection.

My guest’s ancestors have loomed over our lunch, but it is the philosophy of the new patriarch that stays with me. My father “taught me not to look back, and it stuck . . . I don’t spend much time thinking ruefully about what might have been or what was,” he explains. He has, though, thought hard about how much is enough. “Where does happiness come from? Material wealth or treating people well?” he asks rhetorically. His father remembered being given dimes by America’s richest man almost a century ago; Rockefeller, who grew up with below-market pocket money, says he has been similarly frugal with his two daughters. “If you’re flying first-class or private as a kid, where is up from there?”

Andrew Edgecliffe-Johnson is the FT’s US business editor

Follow @FTLifeArts on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first. Subscribe to FT Life on YouTube for the latest FT Weekend videos

Letter in response to this article:

Last week’s Lunch marked a turning point / From Adrian Frost, Grantchester, Cambs, UK

Comments