Security spending ramped up in China’s restive Xinjiang region

Simply sign up to the Chinese politics & policy myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Security and surveillance spending in China’s restive Xinjiang region almost doubled last year as the country tightened its grip on millions of ethnic minority citizens, particularly Muslim Uighurs.

Public security spending rose 92 per cent to Rmb57.95bn ($9.16bn), according to local government statistics, eight times higher than the growth rate for China’s overall public security budget. Xinjiang’s security costs have increased 10-fold in the past decade, vastly outpacing the rest of the country.

The region is the focus of a sweeping overhaul of its security and surveillance apparatus that many observers fear will eventually be rolled out across China.

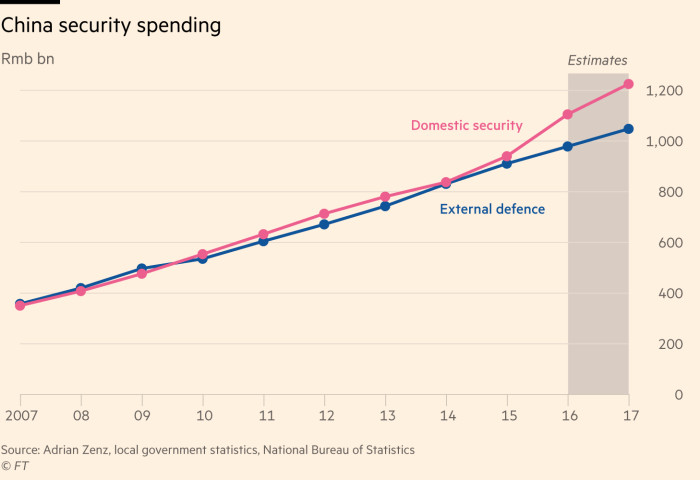

Nationwide security spending reached Rmb1.24tn last year, an 11.4 per cent increase from 2016, according to a report released during the annual session of China’s rubber-stamp parliament that kicked off last week.

The public security budget has risen to be almost 20 per cent higher than that for defence. Domestic security costs first surpassed external defence costs in 2010, the year after deadly riots fuelled by ethnic tension broke out in Xinjiang’s capital of Urumqi.

The ramp-up in security spending comes amid a huge surveillance build-up that began under the leadership of Chen Quanguo, who was appointed party secretary of Xinjiang in 2016. More than 7,000 police stations have been constructed since 2016.

On assuming power, Mr Chen, formerly the top party official in the autonomous region of Tibet, quickly confiscated passports of the region’s 11m Uighurs, banned certain displays of religious behaviour and approved construction of political re-education camps where thousands of Uighurs have been sent.

“The increased security spending is going towards everything from salaries for 100,000 new police that were recruited in 2017 to comprehensive surveillance systems and checkpoints almost everywhere [in Xinjiang],” said Adrian Zenz, lecturer at the European School of Culture and Theology in Germany, who compiled the spending data in a recent paper.

The clampdown has tightened this year, with reports of a purge of the region’s most celebrated intellectuals and leaders, several of whom held Communist party-appointed positions and frequently proclaimed their loyalty to the Chinese state.

“At first they went for anyone who had travelled abroad, then anyone with a criminal record,” said Tahir Hamut, a Uighur poet and film-maker who has applied for asylum in the US. “Now, it is many writers and intellectuals who are targeted.”

Early this year, the heads of Xinjiang University, and the director and vice-director of a Xinjiang publishing house, were stripped of their positions and detained, according to two people familiar with the matter. A high-level official in Xinjiang’s education department was detained at the same time. All were accused of errors in editing elementary and middle school textbooks.

In January one of Xinjiang’s most famous contemporary poets was apprehended, according to two of the poet’s friends.

“The charges seem to stem from online or computer-based “private” data that contradict their public-facing stance as patriotic intellectuals,” said Darren Byler, an anthropologist at the University of Washington who specialises in Xinjiang.

Even those who enjoy local celebrity status are not immune. Ablajan, a Uighur rapper, was recently detained and sent to a re-education camp, according to his brother.

Meanwhile, Uighurs living abroad say that China’s campaign of fear has already spread beyond its borders.

“If I do a very big story, a very sharp one, [the Xinjiang police] will call my parents and threaten them,” said Gulchehra Hoja, a Uighur reporter for the US-funded Radio Free Asia in Washington.

Ms Hoja now has 20 relatives detained or missing, including her parents and several cousins who she says were detained for sending her short messages over Chinese social media almost three years ago. She is one of six Uighur RFA reporters whose relatives have gone missing this year.

“People are afraid to be friends with me. They’re afraid their family will be punished for being friends with me.”

Follow Emily Feng on Twitter @emilyzfeng

Comments