The fight against food fraud

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Behind the bomb-proofed doors of a laboratory in Northern Ireland, a short monotone bell rings: a warning that an electrical current is about to pass through the laser knife that Rachel Hill holds in her blue-rubber-gloved hand. Hill uses the laser knife to score a fillet of fish with a strange tattoo, leaving a burnt stripe. The bell rings again, and she makes another incision.

Next to her, a computer the size of a family fridge is analysing the smoke that rises from the lasered tissue. Thanks to a process involving rapid evaporative ionisation mass spectrometry (Reims), developed at Imperial College London, the computer can identify the smoke’s unique “molecular fingerprint”. This £500,000 machine, together with another £5m-worth of equipment in the Belfast-based Institute for Global Food Security, have inspired the lab’s nickname “Star Trek”, as it boldly pushes technological frontiers in the battle against food crime. The only other Reims machine in the UK is at Charing Cross Hospital, London, where it is used by the oncology department to distinguish between healthy and malign tissue. Here, the machine is being asked to make a formal identification of the fish fillet: is it cod? Or is it something else?

At Queen’s University Belfast, where the institute was established in March 2013, food analysis is inching ever closer to forensic investigation. Fraud, adulteration and contamination can happen to almost any edible commodity that you care to think of. Or, more likely, that you care not to think of — not just beef burgers with a hidden equine component but staples such as fish, spices and fruit juices.

After comparing the fish’s “fingerprint” against a library of species profiles, the computer presents its verdict. This time it’s not guilty: “cod”, reads the screen. But just as often, such tests will reveal fraud — cod mixed with something cheaper, whiting perhaps, or a different species entirely.

Professor Chris Elliott, the institute’s 56-year-old founder and an international expert on food integrity, puts it plainly: “What we eat and where it comes from, generally, we don’t know any more. It’s a very complex web. Every time you have a transaction [in the supply chain], there’s another opportunity to cheat.” And every week his lab picks up several cases of food fraud happening somewhere in the world. “If we think about Europe first of all,” Elliott says, “we pick up more and more reports now about the mafia getting involved in criminal activity in food. Part of that is because in other areas of criminal activity they’ve been involved in, they’ve been clamped down on.”

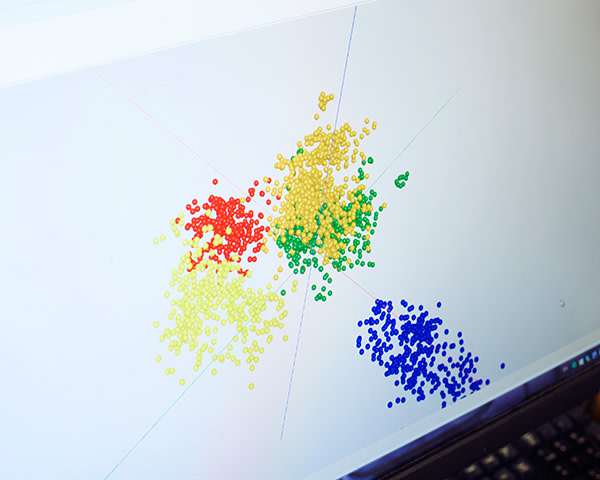

A passing colleague reminds Elliott that he has a pile of non-disclosure agreements to sign; Elliott nods his head ruefully. Samples sent to the institute for testing come from companies around the world, including the UK supermarket chains. Last year, for example, the institute surveyed dried oregano and found 25 per cent of the samples supplied from supermarkets, online retailers and corner shops contained substances other than oregano. Spinning on one of the high-tech screens is a mathematical representation of a new sample of “oregano” dotted with different colours for its adulterant parts: olive, myrtle and hazelnut leaves, as well as sumac, phlomis and cistus. In a little tray on the lab worktop, the green flakes look perfectly innocent. A researcher tests another sample with a handheld device that could eventually be used in key audit points of supply chains. “[In Star Trek] we can do any type of sample and any type of extraction,” says Simon Haughey, senior research scientist.

When the institute does uncover fraud, it does not publicly disclose the source of the suspect samples. “We’d just be inundated with lawsuits,” Elliott says. “I’ve been threatened quite often.” The institute is monitored by 24-hour security — with food fraud as yet hard to bring to successful conviction, any refinement in methods of detection is a potential threat to organised crime. “Quite often when there are seminars about fraud, some of the audience will be fraudsters themselves, because they really want to know what the current state of the art is.”

The complexity of supply chains means that it’s hard to pinpoint complicity: “If we found a fraudulent product in Tesco, I’d be 99.9 per cent certain they didn’t know about it,” says Elliott. “We’re not letting anyone get away with anything — we will tell the appropriate regulatory authority.”

But who is the appropriate authority in the UK? Following the mass corporate embarrassment of “horsegate” in 2013, when Asda, Tesco and others admitted to the unwitting sale of horsemeat products, the government asked Elliott to conduct a review into “the integrity and assurance of food supply networks”. Presented to the government in July 2014, his report made a number of recommendations, chief among them that the UK establish its own food-crime unit. Six months later, the National Food Crime Unit was launched within the Food Standards Agency in London. Its chief executive Andy Morling, formerly senior intelligence lead at the National Crime Agency, told Food Manufacture’s Food and Safety Conference in September: “Where there is money, there’s crime; where there is big money, there’s big crime. The opportunities are certainly there for organised crime to come into food because they have the infrastructures already in place: they own haulage businesses, they own storage facilities, they have money-laundering capabilities, so it’s ready-made, if you like, for organised crime. But I think, for once, we’re ahead of the game.” Last week Morling published his first annual strategic assessment. He says: “The scope of the problem facing us has surprised me and, uniquely in fraud, there is an absence of a vocal victim.” Morling also believes that food businesses are under-reporting the problem: “Is industry reporting to us in the numbers we’d like? I’m not so sure. I don’t like it and I don’t agree with it.”

Though Elliott describes Morling as a “good guy”, he expresses reservations about the Food Crime Unit’s muscle strength. “I get this feeling Andy Morling is finding it really, really difficult to get traction where he is. For the FCU to function properly [with greater enforcement power] it will have to go somewhere else . . . My preference would be the Intellectual Property Office [the government agency] to host it — it looks at crime in different sectors. They are very good at working with other sectors.”

In Elliott’s view, the role of the police in dealing with food crime is a contentious one. How should the police be involved? “There are 43 different police forces in the UK — they are absolutely not joined up at all. One of the questions I sent to them [when conducting the review] was: ‘How many cases of food fraud have you come across in the UK?’, and not one of them came back with any.” He believes the reason they all reported zero is “because on the police database the word ‘food’ doesn’t come up. It would be entered as something else.”

So if counterfeit alcohol was found, for example, it would be classified in other categories. “I talked to a couple of chief constables who showed me the statistics for their region — ‘These are the murders, these are the rapes. Do I have the resources to check if this is cod not haddock? I can’t do it.’”

Last year, the Food Standards Authority conducted a dry run, named Exercise Prometheus, to test its Incident Management Plan in the case of a major food scare. The “scenario” was mycotoxin contamination of grain imported to the United Kingdom and an outbreak of E. coli O157 in Northern Ireland. In its “post-exercise report” the FSA declared the operation a success. Elliott says: “If there’s another incident, which I believe there will be, we will have the National Food Crime Unit there, and the expertise will be there to immediately take action.”

Yet one of the striking elements of the horsemeat scandal is how few convictions resulted. “Nobody took responsibility in the first place — it was like the poisoned chalice passed around the [government] departments. A huge amount of credit to Owen Paterson [then secretary of state for environment, food and rural affairs], because he stood up and said, ‘Look, give it to me, I will run with it’ — nobody else did.” But, Elliott adds: “I know Paterson found it very difficult to engage with the police . . . Finally, the City of London police said they’d run with it because they specialise in fraud. That took three months to organise.

“Now, if you’re gathering together your posse to chase the bad guy and you give them three months to get away, that’s a reasonable amount of time to escape over the horizon. And that’s what happened.”

. . .

A suspicious package caught the attention of customs officers in Nijmegen, eastern Holland. It was labelled as 5kg of baking powder. Why bother importing just 5kg? The officers opened it, and inside was 17 beta oestradiol, an illegal growth hormone used to artificially stimulate growth in meat production. Such drugs have been banned by the EU since 1989. “It was funny,” says Karen Gussow, an inspector at the Netherlands’ Intelligence and Criminal Investigations Service, as she describes what she and her colleagues did next: “We replaced it with actual baking powder.” It was then sent to the intended recipient with a hidden tracking device. He collected his delivery and was followed to a hotel in Emmelord in the north. “He was expecting a package — and we came with it. He got 18 months.”

Gussow works in an investigative team of 125 people. They operate within the Netherlands Food and Consumer Product Safety Authority, which tracks illegal activity in agriculture and animal health and welfare. “Because we are very focused on fraud we can make links,” says Gussow. Unlike the British unit, they can also make arrests: “We are the in-house police, our capabilities are the same as the police. Everything you see on CSI — we can do that, we just don’t have guns. We can observe and interrogate, we can intercept email and telephone.”

The Dutch unit was cited in Elliott’s report as one that manages enforcement well. It pursued, for instance, the successful prosecution of Willy Selten, the man who ran the cold-storage business where horsemeat was switched for beef. “One of the best jokes I’ve ever cracked was that Selten has traded horsemeat for porridge,” says Elliott. Selten is, however, currently at liberty while he appeals his two-and-a-half-year sentence — the longest ever given in the Netherlands for this type of crime.

“We act when we find fraudulent cases where we see a relationship with food safety,” Gussow notes. “With Willy Selten — the reason we did it [pursued prosecution], was because it frustrates the traceability of the food. If there’s something wrong with the meat and you have to get it back, you can’t.”

In addition to regulatory inspections and tip-offs or complaints from third parties, the Dutch unit relies on another specialist team which works with anonymous informers and passes on information without any identification as to its source. “None of us knows if it’s one or two people, or whether the source is within the company, or if it’s a neighbour or a driver.”

In a recent case investigated by Gussow’s intelligence team, slaughterhouse meat waste — known as “category 3 animal byproduct” and used in pet food — had been relabelled as fit for human consumption. “It was bought in Germany, stored in a Dutch cold store and sold to other EU countries, where it ended up, indeed, in minced meat and also in sausages.”

Cases like these, Gussow says, “give us in-depth information about what the world really looks like. It gives us a lot of information that we feed into the government who devise regulations and can adjust these, or we feed it into the inspectorate to sharpen inspections. So it completes the learning cycle.” Gary Copson, a police adviser to the Elliott review, says: “We should aspire, over five or six years, to match the Dutch investigations.”

Since 2011, the international police organisations Interpol and Europol have annually co-ordinated their food-fraud investigations under the operational title of Opson — a Greek word for food. When Opson I ran, there were 11 countries involved; now there are 47. Chris Vansteenkiste, Project Manager of Europol’s counterfeiting team, says: “Each year, it’s becoming bigger and bigger, like an oil spot.” Opson V will report its findings in the next few months: previous case stories have revealed a wide range of contraband activity, from counterfeit vodka in Derbyshire, England, to a factory in Abrezzo, Italy, where eastern European curds were being sprayed with chemicals to imitate fresh mozzarella.

Vansteenkiste says: “In former days, we had fake champagne, vodka, Johnnie Walker whisky. What we see now is day-to-day consumer goods, [things like] tomato juice and orange juice. You wouldn’t expect it for a low-priced item like tomato juice — for God’s sake, why would they fake it? The answer is people don’t expect it to be cheated, and the profit is very low, but people drink more tomato juice than champagne.”

Tomato juice is usually adulterated by diluting a famous brand name with a cheaper product. Chocolate, coffee and cookies are also targets, says Vansteenkiste. This spread of fraud poses a particular brand risk to companies with established reputations. In response to the horsemeat scandal, PwC, the financial consulting firm, introduced a food-supply-chain consultation as one of its services, and has estimated the global trade in food fraud to be worth around $40bn a year. Hans Schoolderman, European leader of PwC’s food supply and integrity services, says: “Companies think, ‘It won’t happen to me — it will happen to another.’” But the multinational companies that PwC works with need to be aware of the risks: “How are you negotiating contracts with your suppliers — are you putting suppliers under pressure, and could that trigger fraud? It’s about asking your suppliers to provide you with information, it is nitty-gritty and it’s not an easy task.”

Vansteenkiste adds that now “we’re seeing a shift in behaviour — in some cases, the target is already known to have a career in the drug-related scene. They have noticed they can earn money [in food fraud] and the chance of being caught is less high. Multinationals have a multi-segment approach, they try to diversify — the [Camorra] in Naples do the same, they diversify.”

. . .

Chris Elliott grew up on a farm in County Antrim. “But everybody in Ireland has a farm,” he laughs. “It’s compulsory. A lot of us come from a rural background.” On the farm just outside Antrim Town there were “a few dairy cows, a few beef cows, fields of potatoes and strawberries and raspberries at the right part of the year. Quite typical.”

At first interested in marine biology, Elliott then became involved in veterinary science. “In the late 1980s and early 1990s there was this drive in looking at the misuse of drugs in animals — and I got very interested in that.” He worked at the Northern Ireland Science Service, a government agency, for 20 years before joining Queen’s University, Belfast, as professor of food safety.

A family farm is one sure way to know where your food comes from. Indeed, Elliott believes that provenance will be at the root of the next big scandal in British food consumption. “What will happen at some stage is that you think something is produced in the UK and it won’t be — that will be a shocker.”

And then there’s fish. “Norway and Russia dominate the world’s fishing industry — they invested heavily and built a huge number of these factory ships. Now, what happens to that fish?” (Elliott likes rhetorical questions.)

“What they do is what’s called ‘H and G’ — they take the head off and cut the guts out. Then they take all of those fish to another country. The vast majority of filleting of fish happens in China because they employ tens of thousands of women to fillet the fish — the women are better at filleting fish than machines, and they’re cheaper.” Next, the fish is frozen into 7.5kg blocks and shipped to South Korea, “because it has the world’s largest cold stores. They have massive cold stores, the size of Wembley Stadium. The buyers go to South Korea and traders will come and buy different amounts in different commodities of fish, and sell them on to other traders and then sell them into companies.”

It is after the fish is bought in these blocks that the supply chain control is lost. So a fish that was “caught 50 miles off the north coast of Scotland has been to China, has been to South Korea, and probably been to a couple of countries in between. What arrives back in a port in Scotland is a 7.5kg block of fish and you’re told, ‘That’s cod.’” A number of different fish frauds can be committed — Elliott calls them the “sins of sea fish” — substituting species, bulking up fillets with salty water, switching bulk catch for line-caught labels, deceiving on quotas.

“If we think about the UK, virtually all the processed fish that goes into any ready meal or any frozen product will have come through that supply chain.” Elliott makes it clear that the “big guys”, such as the supermarkets who run the greatest reputational risk through mislabelling, will keep close track of their fish supply chains. “They will not buy off intermediaries — they will send people out to the cold stores . . . They will do quite a lot of testing whenever fish arrives at the port in the UK.”

False identities in a fish finger do not touch quite the same level of taboo as minced horse in a lasagne. (Though Young’s Seafood, which owns Findus UK, whose frozen lasagne tested positive for horsemeat, would doubtless not wish to test that theory.) The cultural sensitivities around food do play a significant part in how regulatory bodies respond to public fears. This, explains Elliott, will be a particular concern in China, where “scandal after scandal” has upset the country’s large middle-class population. Food crime there has involved “gutter oil” being siphoned up from the drains where street food stalls have been trading to be refiltered and resold. Or melamine in milk powder that poisoned hundreds of thousands of babies. To counteract the risk of a domestic boycott of Chinese products and stem the flow of scandals, Premier Li Keqiang declared “zero tolerance” last year for violation of China’s tightened Food Safety Law.

As a self-confessed food-fraud “anorak”, Elliott keeps a close watch on developments around the world, particularly with regard to climate. “What [climate change] does is create massive perturbations in supply and demand. To give an example, in Southeast Asia there was a failure of the cumin crop in the tail-end of 2014. Cumin is sold through very complex supply chains. It’s grown in different regions of Southeast Asia, places such as Vietnam and India, and it’s transported to big processing facilities in Turkey — a big processor of herbs and spices.

“We picked up reports of people getting ill from eating cumin in Canada. They were getting ill from anaphylactic shock from eating curries.” The cumin had been cut with peanut shells. Small retail businesses selling spices in larger quantities may buy direct from their countries of origin — which provides another opening for organised criminals to penetrate supply chains that are not as heavily regulated, says Elliott. (Small businesses with late opening hours are also being looked at as a focus for investigating the distribution of counterfeit alcohol, according to Chris Vansteenkiste.)

Elliott says he declined through fear an invitation from a Turkish processor to fly over and tour its facilities. “I thought, ‘I don’t think I’ll do that, because I’ll probably never come home again.’” There is a distinction between criminals and fraudsters in the food trade — “criminals are quite stupid and will get caught,” he says. “Fraudsters are generally very smart and don’t get caught. It’s fraudsters we’re generally thinking about here”.

Natalie Whittle is associate editor on FT Weekend Magazine

Photographs: Daniel Stier/ Twenty Twenty; Paddy Kelly; Getty; Alamy

This article has been amended since its original publication to correct name of the Camorra in Naples

Comments