Western schools lead the way to China

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The past six months have passed in a whirl for David Medina. Until January he was studying hard at Duke University in North Carolina; now he has swapped the leafy Durham campus for Duke’s spanking new venue in Kunshan, close to Shanghai.

The two are worlds apart, says the management student from the Dominican Republic. “I was prepared for the huge number of people that live here, but it has really surprised me how rush hour (especially in Shanghai) is almost a life or death adventure,” he says.

It is just such experiences that Fuqua dean Bill Boulding believes brings real value to Duke’s inaugural two-country Master of Management Studies (MMS) degree, on which close to half the participants are Chinese, the other half from around the world. “The common denominator is people who want the opportunity to be in the US environment and the environment in China,” says Prof Boulding.

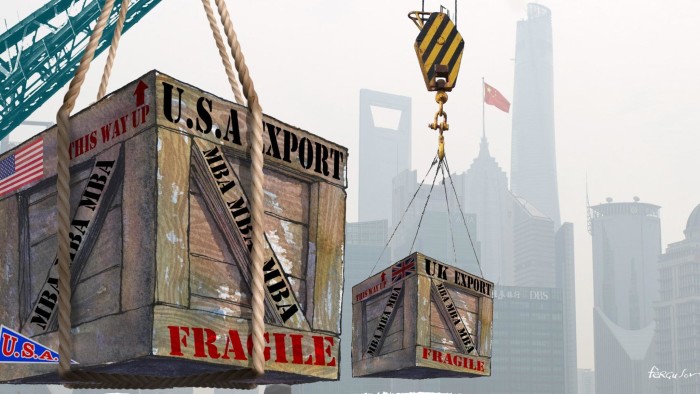

This meeting of cultures, a 21st-century version of the silk road, is a notion that resonates with students in the US, Europe and China alike. While the past two decades have seen top Western universities — and business schools in particular — launch joint programmes with Chinese universities, there is now a move afoot for them to enter a new phase of commitment, in which they invest in bricks and mortar in China.

New York University joins Duke University from the US and Liverpool and Nottingham universities from the UK as the clear leaders in this enterprise. And what is apparent from all of them is that it is the business programmes that are proving most popular and will determine the future of these institutions.

These pioneers are just the tip of the iceberg, believes Eitan Zemel, associate vice-chancellor for strategy and dean of business for NYU Shanghai. “I think it is only the beginning. I think there is something much bigger ahead of us,” he says.

MBA

The residential MBA, the flagship programme of all the big-brand US business schools, is as much about building reputation as earning hard cash. And so it is that while established universities such as Duke and NYU rely on masters and undergraduate students for their business programmes in China, newcomer International Business School Suzhou (IBSS) at XJTLU, in which the UK’s University of Liverpool is a partner, plans to launch a full-time MBA in September 2015.

“We are a new business school and we need to launch an MBA to succeed worldwide,” says Roberto Dona, head of MBA Programmes, who believes there will be strong international demand. According to the Graduate Management Admission Council, he says, 40 per cent of MBA graduates worldwide are employed in projects that are in Asia or related to Asia.

The school is planning to enrol 40-50 students on the 15-month programme, which will exploit the school’s China knowhow. The second term, dubbed the “New Silk Road”, will include residencies around China and the opportunity to learn the Chinese language. The third term will focus on emerging industries.

It is a similar tale at NYU, which has 15 sites around the world. Nottingham University also has a campus in Malaysia as well as Ningbo, where it established its China campus a decade ago.

But there is also a real sense that China’s generous welcome to these institutions is part of its own need to modernise its higher education system, says NYU’s Prof Zemel. “I think China is now struggling with the next phase of economic development. They have done a good job but they know that low-cost is running its course,” he says. The next phase is to invest in innovation and this means changing the way students are educated more widely.

“The objective of NYU in Shanghai is not to educate the 2000 [enrolled] students,” says Prof Zemel, “but to have a long-term impact on other institutions.”

It is a message echoed by Prof Boulding about Duke’s three-way partnership between the university, local government in Kunshan and Wuhan University. “They [Wuhan University] felt this was a great opportunity for them to drive learning and education for that university. What we wanted to do was send a signal that this was a different kind of programme in China, where east meets west”.

Under attack is the traditional stereotype of Chinese tertiary level education, in which passive learners listen in awe to the wisdom of esteemed professors. One hundred kilometres west of Shanghai on the Suzhou Innovation Park, Sarah Dixon, dean of the International Business School Suzhou (IBSS) at Xi’an Jiaotong-Liverpool University has gone one step further than the others and organised formal teaching for professors from local Chinese universities.

Critical thinking and student-centred learning are two of the hot topics on the three programmes at XJTLU — a leadership programme and training programmes for both teaching and administrative staff. In the past three years, more than 150 senior managers from some 70 Chinese universities attended the leadership excellence programme alone. This year will see a steep increase in the number of these trainees.

As such XJTLU, which teaches its programmes in English, is a model for future Chinese universities. “We would certainly hope that our university would be emulated by others in China,” says Prof Dixon.

Women in Business Q&A

Read our interview with Camille Hamel, a masters student at Skema’s Suzhou campus specialising in fashion and luxury management.

Just a stone’s throw from XJTLU, France’s Skema business school is training Chinese entrepreneurs rather than professors. It runs two business incubators, says Paul d’Azemar, director of Skema’s Suzhou campus. “The idea is to train Chinese engineers to start their own businesses,” he says. “They [the Chinese] don’t want to be the workshop of the world. They want to be part of the world economy.”

These institutions may be the first to open campuses in China, but they are unlikely to be the last. However, this head start should stand them in good stead, says Carl Fey, dean of the business school on Nottingham University’s Ningbo China campus. “It’s understanding how things work, it’s about having a network of alumni in China.”

For Mr Medina, a career in China is certainly on the cards at some point in the future.

“I have been highly impressed by the ongoing development of this country. Shanghai is an architectural marvel and everywhere I look there are cranes being set up for building high rises,” he says.

“It is obvious why this is one of the fastest-evolving economies in the world.”

Comments