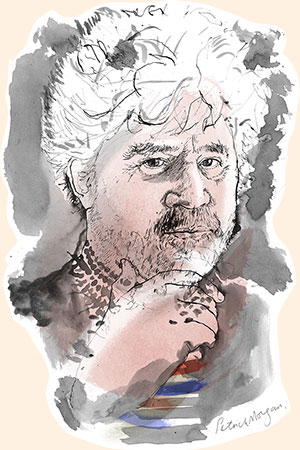

Tea with the FT: Pedro Almodóvar

Simply sign up to the Life & Arts myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Soho in London used to be synonymous with debauchery — a haven for sex shops, drug dealing and subterranean dive bars — but today the area is acquiring an air of respectability. Hipster hang-outs increasingly outnumber seedy sin palaces, to the point that some people want parts to be granted protected status. Strip joints as cultural heritage.

What better place, in London at least, to meet the film director Pedro Almodóvar, who scandalised Spain’s establishment when he emerged in the early 1980s with his irreverent tales of sex, drugs and rock ’n’ roll, yet today is one of its most revered cultural figures?

We rendezvous in a small private dining room at the Soho Hotel and Almodóvar appears wearing a maroon bomber jacket, a black-and-white print scarf and a warm smile. At 65, he still sports an enviable hedgerow of hair but it is white these days, and he complains of being extremely light-sensitive and not hearing well in one ear. We arrange ourselves accordingly.

Almodóvar is in London to attend an early preview of the stage musical adaptation of Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown, the frenetic 1988 comedy that first brought him to the attention of a wider international audience. So it is fitting that our conversation begins in much the same way as this famous movie — with the business of dubbing.

In the film, Almodóvar’s frequent collaborator Carmen Maura plays Pepa, a voiceover actress abandoned by her lover (and dubbing co-star) and left with only the sound of his voice. The set-up is quintessential Almodóvar. It is at once a love letter to cinema and a picture of female fortitude: Pepa carries on regardless of the hardships that life, and in particular men, have thrown at her.

“I hate dubbing — it was used by Franco as a form of censorship,” says Almodóvar, “but as a complementary language of cinema it interests me greatly. Two people in front of a screen trying to synchronise their lips with what is being said on screen; it’s a ritual that is enthralling to me — it converts film into something almost sacred.”

For my part, as a non-native speaker of Spanish, I feel as if I have been badly dubbed into the language as we make small talk and pour English breakfast tea from a dainty porcelain set. Fortunately, Almodóvar is an effusive and expansive conversationalist who is happy to do most of the talking in an excitable, rapid-fire Spanish between mouthfuls of scones. These have been specifically requested by the scone-loving director and we tuck into them heartily while a multi-tiered display of other delicacies stands mostly untouched.

. . .

The issue of linguistic differences is pertinent in another way. After a short run on Broadway in 2010, Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown has been reworked with new songs, and stars British comedy actress Tamsin Greig, seemingly a perfect fit for a spirited “chica Almodóvar”, as the actresses who repeatedly work with the director are known in Spain. But can an English-language adaptation really hope to capture what the writer/director calls “the musicality” of his dialogue, let alone the essentially Spanish flavour of the work?

“You have to convert it into something different,” he says emphatically. “The director [of the musical], Bartlett Sher, was very concerned with fidelity but I kept telling him that I gave him all the freedom he wanted — and to the adaptor Jeffrey [Lane]. I trusted them, and was obsessed that they took all the freedom in the world and that they weren’t overwhelmed by my shadow, by my presence. I intervened only when there were things they didn’t understand clearly, so that there weren’t any big mistakes.” Nevertheless, he says, there are some elements that will inevitably be lost in translation. “For example, Candela, played by María Barranco in the film, looked very modern, young, pretty but I encouraged her to use Andalucían expressions that her grandmother used . . . she’s speaking a very regional and old-fashioned Spanish, so it’s impossible to translate. I did it simply because it was very funny.”

Almodóvar’s cinematic career stretches back more than three decades and this year will see him shooting his 20th feature. He is best known as a purveyor of high-camp comedy and melodramas centring on women. But he has been promiscuous as well as prolific, dipping into genres as the fancy has taken him, including elements of the thriller (Matador in 1986, Live Flesh in 1997) and psychological horror (The Skin I Live In in 2011), though always subverting and twisting each into his own distinctive style.

Many of his films feature standout scenes in which characters perform songs (Penélope Cruz in Volver, the director himself in Labyrinth of Passion), yet Almodóvar has never made a full-length musical. “I’ve always been at the edge of the musical genre,” he says, “but [if I were to make one], it would always be a dialogue-based film in which there are musical elements. I see myself doing something like that but in the style of Woody Allen when he made Everyone Says I Love You, in which everyone sings . . . I love the musicals of Vincente Minnelli and Stanley Donen but for me great musical cinema ends with West Side Story, which was a monumental work. If I found a score like that, I’d love to make it but that’s very hard [to find].”

Most recently, Almodóvar has revisited the genre in which he began working: bawdy comedy. In I’m So Excited (2013) a planeload of passengers and crew circles Spanish airspace getting increasingly drunk, randy and out of control. Many saw it as an extended metaphor for the turbulent state of Spain itself.

I’m So Excited was a success at the domestic box office but, unusually for Almodóvar, failed to win critical acclaim. “In general [comedy is] considered a lesser genre,” he says. “But, on the contrary, it’s a superior genre, especially the way Ernst Lubitsch or Billy Wilder did it. In Wilder’s films all American society was reflected, even though he was an Austrian.”

Could it be that comedy is taken as entertainment in its own era and only gains deeper significance over time? “Yes, but time can also destroy,” says Almodóvar. “Time is very cruel to cinema, more so than to literature in my opinion. But I’m very happy because time has respected me. Many critics in Spain haven’t but I don’t care about that. I value time more than [I do] the critics.”

The director has no intention of turning his back on the form just because he has won acclaim for his dramas. “I’d love to make another film like Women on the Verge but I haven’t managed it. Looking back on the film . . . it’s a fictional comedy but, over time, it seems to absolutely represent the 1980s in Spain, the era in which it was made. Without me having intended it, it captures the tolerance of the time, the joy of living at that time.”

Almodóvar came to prominence during “La Movida”, the Madrid counterculture that, following Franco’s death in 1975, enthusiastically cast off the oppressive mantle of dictatorship and embraced hedonism alongside sexual and political liberation. With their colourful and brazen depictions of modern Spanish life, Almodóvar’s earliest films shocked audiences and critics alike.

This power to shock remains intact. In preparation for our meeting I made the mistake of watching Pepi, Luci, Bom and Other Girls On the Heap (1980) on a laptop while riding the London Tube. Within the first 20 minutes of Almodóvar’s crudely shot debut feature there is a rape scene and an eye-popping encounter in which a young punk girl walks in on a knitting class and urinates on a masochistic Madrid housewife who purrs with delight. Already attracting disapproving looks from my fellow passengers, I only just managed to snap shut the laptop lid before she hoisted up her skirt.

Such extreme examples aside, the kind of domestic transgression with which Almodóvar made his name can today be found in mainstream US television series such as Desperate Housewives, Nurse Jackie and Breaking Bad. “I think at the moment in the US they’re producing TV that is much closer to reality than the cinema is,” he says. “Breaking Bad is like early Scorsese, the most brutal, most acid television. And, over five series, every episode is a masterpiece of scriptwriting, direction and exaggeration — not that they exaggerate reality but that they’re dealing with a reality that is already very extreme. Breaking Bad, I think, is the culmination of American fictional TV.”

In this regard, he says, it is outstripping film. “Film-making is a business but [the Hollywood studios] shouldn’t forget that there are other ways of making movies . . . What I see is an absence of these other options for making cinema that is more personal but can also entertain people.”

It is for fear of falling foul of such restraints that Almodóvar has so far resisted the advances of Hollywood, which has long been trying to woo him, especially since his two Oscar wins — for All About My Mother in 1999 and Talk to Her in 2002. “I might make a film in English but not necessarily in Hollywood,” he says. “They offered me Brokeback Mountain but I had many doubts. Thinking about it, I don’t know if I made a mistake or not [in turning it down]. They promised me total artistic freedom and final cut but it was a story that was so physical — it’s not just that the characters sleep together once — and that has to be there. I think Ang Lee went as far as he could and I like his version very much. But I always imagined it differently and I don’t think I would have been able to make it the way I wanted. They wouldn’t have let me.”

Fortunately for Almodóvar, and despite Spain’s economic woes, he can still finance his films and make them en casa, as he puts it. But he is under no illusions: “For me it’s fine, but I’m an exception,” he says. “I know many Spanish directors who are making their films in a co-operative. No one is paid a penny, not they or anyone in the crew.”

. . .

Almodóvar is no stranger to meagre beginnings. He was born in a small village in La Mancha, where his father worked as a mule driver. Later the family moved to a village in Badajoz, where his mother started a business reading and writing letters for illiterate neighbours, sometimes embellishing the truth with her own fictitious inventions, a practice that made a lasting impression on her young son. After moving to Madrid in the late 1960s he worked for the communications company Telefónica and began experimenting with making Super 8 films in his spare time.

Yet, he says, the situation facing fledgling film-makers in Spain today is much worse. His voice grows in indignation as he talks about the paucity of funding available to them. “There are lots of directors today trying to make films for €3,000, €5,000 or €10,000. Suddenly that seems to them a way of making films. But it’s not — that’s desperation. And it cannot develop into anything because these crews have to live on something. I made my first film, Pepi, Luci, Bom, that way with a bit of money raised from various people — 400,000 pesetas — you can make your first film that way but it’s not sustainable.”

Falling cinema attendances have compounded the problem, he says. It wasn’t until his teens that Almodóvar had regular access to a cinema and began bingeing on domestic and foreign films. So he laments the modern decline in cinema-going and does not see watching films on computers as a satisfactory alternative. “Youngsters have less money and have grown up in a technological age and don’t have the habit of going to the cinema and that pains me terribly — not for the money we lose but because what they watch is substandard.”

He is also critical of the role played by the ruling Spanish government of the rightwing Partido Popular. “These past three years have been horrific,” he says. “I never thought we’d be living in a social situation that we are living in now — to return to hearing about the hunger of the 1950s, the years in which I was born. But now you hear of it again in the cases of families, children. Certainly if it was up to [the government], it would have taken us back to the 1950s. But, fortunately, what has grown in Spain is the civil society which is a universal society, not one of political parties.”

He points to protests in Madrid last year by doctors and auxiliary staff that helped prevent the privatisation of the social security system, and believes that elections will see “everything change” in 2015. “Three years is enough for people to realise that the government doesn’t listen to what they want.”

Our time is nearly up and an assistant has slipped quietly into the room. So what of the director’s next film, of which there have so far only been rumours? “The script is finished and we will shoot in April,” he announces. “We are involved in casting at the moment, which is complicated because what I’ve written doesn’t quite work with my actores amigos.”

The director turns to his assistant and asks whether he is allowed to reveal the name of the film, which so far has not been announced even in the Spanish media, and she leaves the room. “It’s a return to the cinema of women,” he continues in the meantime, “of great female protagonists, and it’s a hard-hitting drama, which excites me.”

The assistant returns and whispers into his ear that he may indeed reveal the title. “It’s called Silencio because that’s the principal element that drives the worst things that happen to the main female protagonist.”

The Soho Hotel

4 Richmond Mews, London W1D 3DH

Christmas afternoon tea (x2) £22.50 each

1 bottle Evian £4.75

Total (inc service) £54.95

The interview concluded, we are greeted by Agustín, Almodóvar’s producer since 1987 and his younger brother for even longer. (He also makes Hitchcock-like cameo appearances in many of Pedro’s films.) The two are about to be whisked away for their night at the theatre. I ask Agustin what the Spanish equivalent of “break a leg” is. “Mucha mierda,” he announces with a gleeful chuckle. We agree that in Spain there’s often a scatological component involved, not least at this time of year when the figure of el caganer (the defecating man) adorns nativity scenes in many regions.

It is the kind of subversive, picaresque touch that wouldn’t look out of place in one of Almodóvar’s early films. Bad taste as part of cultural heritage — not such a new concept after all.

‘Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown’, now previewing at the Playhouse Theatre, runs from January 12 to May 9.

Raphael Abraham is the FT’s assistant arts editor

Illustration by Patrick Morgan

Comments