© The Financial Times Ltd 2016

FT and 'Financial Times' are trademarks of The Financial Times Ltd.

The Financial Times and its journalism are subject to a self-regulation regime under the FT Editorial Code of Practice.

June 22, 2014 6:45 pm

The US Chamber of Commerce calls it “minoritarianism, the tyranny of a minority”. Dan Gallagher of the Securities and Exchange Commission says annual meetings have been “hijacked” by “corporate gadflies”. Leo Strine, the chief justice of Delaware, where most big US companies are registered, says shareholder democracy has wrought a “constant ‘model UN’ where managers are repeatedly distracted by referendums on a variety of topics proposed by investors with trifling stakes”.

The annual meeting has become a venue for the debate where campaigners from nuns and father-and-son teams to unions and pension funds raise hundreds of proposals to challenge imperious chief executives on issues ranging from their pay to the environmental sustainability of their operations.

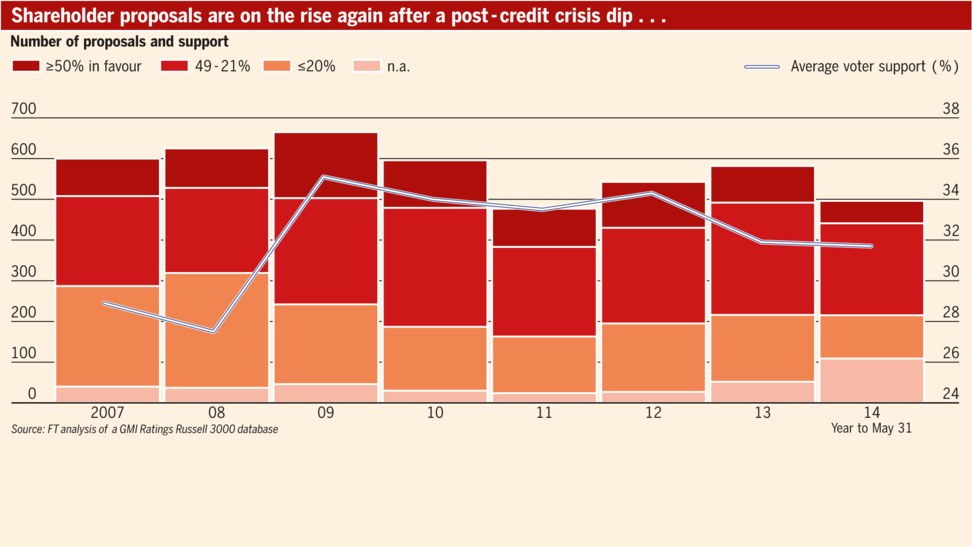

While the financial crisis initially broke the feverish rush of such actions, the total has crept back up, according to a Financial Times analysis of data provided by GMI Ratings, a corporate governance consultancy. “The kinds of proposals forwarded by a lot of these individuals are about core issues of shareholder rights, things that are broadly supported by the institutional investors,” says Gary Hewitt, GMI’s head of research. “In a world of dispersed ownership, there is a free rider problem, where no one will step up, and these individuals are stepping up.”

Yet as another season winds down in the US, the Chamber of Commerce has launched a campaign to turn back the tide. The renewed activity is one reason the organisation has revived the pushback. Another factor is a new proposal to force companies to disclose or restrict political donations that threatens to undercut the lobbying of the chamber itself, which is funded by corporate members.

The FT examined GMI Ratings data covering eight years of activity among the Russell 3000 index of US-listed companies. It shows that 321 last year faced 582 proposals, up from a post-crisis nadir of 477. With more than three-quarters of annual meetings passed, 2014 shows rising volumes and breadth of activism, with many companies acceding to proponents’ demands before they can reach a vote.

In the past few weeks, shareholders at newspaper publisher Gannett voted against the use of golden parachutes for executives; Harley-Davidson, the motorbike maker, lost its attempt to block the introduction of majority voting for directors; and over 50 per cent of votes at oil refiner Valero Energy demanded more transparency in its lobbying efforts (although abstentions meant the proposal did not pass).

It remains unusual for a shareholder proposal to pass when directors are opposed. In all, 55 proposals won majority support by the end of May this year, but 332 had been defeated, a typical proportion. Successful votes on social or environmental policies can be counted on the fingers of one hand each year.

The topics of shareholder proposals are diverse. Many concern how companies are governed, boards are elected, executives paid and the openness of companies to outsiders such as activist hedge funds or hostile bidders. For proponents, including a small club of dedicated individuals who account for an outsize number of these proposals, the process is democracy in action – accountability at last for corporate boards.

Other proposals seek to influence a company’s policies on the environment, or towards its workers, its place in society or role in the US political system. A wave of activists, from religious orders to unions to single-issue campaign groups, are also explicitly using shareholder proposals to further their social and political goals by changing corporate behaviour.

The number of shareholder proposals first jumped a decade ago, according to GMI Ratings, which has its longest history of data for the S&P 500. Those 500 companies last year faced 431 votes, up from 204 in 2000.

Opponents say many of these additional proposals are a frivolous use of company time and money. However, the bulk of votes are on corporate governance issues that have garnered considerable support from institutional shareholders in recent years.

The top 10 most prolific proponents sponsored 34 per cent of all proposals since 2007. John Chevedden, a one-man corporate governance machine, sponsored 6 per cent. He was involved behind the scenes with at least as many again, on behalf of more than six other individual shareholders.

Mr Chevedden, 68, who put forward his first shareholder proposal at General Motors in 1994 after he was laid off from its Hughes Electronics division, has garnered an average 41 per cent support for proposals submitted since 2007. More than a quarter have won a majority of votes.

Mr Hewitt at GMI credits Mr Chevedden and others with catalysing recent corporate governance improvements. These have included requiring unopposed directors to win a majority of votes to get elected, and ending the system of staggered board elections, which stood as a block to hostile takeovers because bidders could not unseat all the recalcitrant directors quickly. More recently, a favoured cause has been separating the roles of the chairman and chief executive, reflecting perceived best practice in Europe.

Not every proposal is allowed on to the ballot. Companies can apply to the SEC to have one excluded if it touches on what is called their “ordinary business operations” rather than matters of policy. Proponents also have to prove they own or represent the minimum required shareholding of $2,000. Proposals can also be excluded if they attract only de minimis support. The thresholds are 3 per cent for a proposal put for the first time the previous year, and 10 per cent for one that has appeared three years in a row.

Opponents say the exclusions ought to be broadened and shareholders should have to hold larger stakes or club together to put forward proposals. Mr Chevedden disagrees. “Frankly, there are not enough proposals filed,” he says. “A lot of companies don’t get any proposals at all. Companies may have adopted some of these good governance practices but executive pay keeps going up.”

While corporate governance issues have garnered widespread support, more contentious are shareholder proposals that stray into social and environmental policy and politics. Most are framed in terms of reputational risk: that a company ought to disclose to shareholders its policies on issues such as human rights, carbon emissions and political donations so investors can judge the risk that corporate actions could end in a scandal.

But Mr Gallagher, the chamber and others say the aim is to embarrass companies, while subsequent disclosures are grist for protest groups that want a company to change course.

Thomas DiNapoli, New York state comptroller, disagrees. “There are inherent risks when companies spend money on politics that, without disclosure, shareholders have no way to assess,” he says. “As fiduciary to the New York State Common Retirement Fund, I firmly believe that disclosure is tied to protecting the long-term value of our investments in these companies.”

John Harrington, who began his shareholder activism trying to get corporations to divest from apartheid-era South Africa, offers a philosophical justification for taking these campaigns to the annual meeting.

Companies are not primordial organisms, he says; rather they exist because of historic laws to allow businesspeople to limit their liabilities. These “state-created institutions” exist within society and within the political sphere, and as a result have responsibilities. “Over the years we have learnt that writing letters and having phone conversations doesn’t get you very far,” he says. “To have a positive influence, you have to get their attention first of all.”

Some of the most active proponents are Catholic institutions. The GMI database includes almost 150 proposals sponsored by orders of nuns, notably on the environment. Sister Pat Daly represents 40 Catholic institutions in the Interfaith Center on Corporate Responsibility. Money saved to pay pensions and healthcare for nuns can be used now to do good, she says. “When you sell your stock you lose any opportunity for preaching. These portfolios have a mission beyond making money. We are not going to be blind to the impact of the portfolio.”

Sister Daly has been a leading voice in Campaign ExxonMobil, which aims to get the oil company to quickly switch its business to renewable energy. But proponents at Exxon have averaged only 22 per cent support compared with the 32 per cent average for all proposals over the past eight years.

GMI’s data confirm that contentious industries receive an outsize proportion of proposals. ExxonMobil and Chevron together have dealt with 136 dissident votes since 2007, for example. But the breadth of activism seems to be widening. Consumer goods companies are growing in popularity as the targets of activists. While banks have attracted numerous high-profile campaigns, such as that to split Jamie Dimon’s roles of chairman and chief executive at JPMorgan, the sector accounted for only 5 per cent of proposals so far this year against 20 per cent in 2008, when a Québécois activist was targeting Canadian banks.

The costs of dealing with hundreds of shareholder proposals annually are hard to pin down. Big institutional investors have substantial corporate governance departments engaging with their investee companies on these issues year-round; smaller investors outsource many of the decisions on how to vote to proxy advisory services such as ISS.

An SEC report based on data more than a decade ago estimated the cost to a company of assessing, responding, distributing and tabulating support for a proposal at $87,000. “It is not an overwhelming burden for a corporation but it is a pain, and an unnecessary diversion of attention,” says Martin Lipton, corporate lawyer and founder of Wachtell Lipton.

Many proponents measure the success of their proposals not in wins but progress in building support between successive annual meetings – and keeping them above the SEC threshold for inclusion the following year.

In a speech in March, Dan Gallagher at the SEC proposed doubling the eligibility requirement to 20 per cent support after three years. There appears to have been some decline in supposedly frivolous proposals. Two in five proposals failed to reach 20 per cent support in 2007, but only one in five has failed to meet that target so far this year, suggesting an improved seriousness among proponents.

The big institutional shareholders, whose support is vital if a proposal is to pass, are sceptical of those which demand specific new business practices, particularly in human rights and environmental fields. Instead, they prefer less threatening proposals that ask only for extra transparency and clearer corporate policies.

Activists argue the low number of successful proposals understates their impact. Many are withdrawn before the annual meeting when the company agrees to the demanded policy changes, as ExxonMobil did this year in promising to disclose risks associated with fracking.

For Mr Gallagher, these eleventh hour agreements are cause for consternation, not celebration. Even the less threatening proposals to produce reports and increase transparency come with real administrative costs.

“Management should be focusing on the business rather than fending off another Chevedden proposal,” he says. “All too many companies fold, and there is an argument that they are selling out shareholders just to get rid of this nuisance.”

Activist tactics: Gimmicks, gadflies and appeals to concerned citizens

When Kenneth Steiner stood up to ask questions of the imperious Saul Steinberg, chief executive of Reliance Group, in 1977, attendees at the annual meeting were stunned. Mr Steiner was just 11 years old.

Mr Steiner recalls how he had learned investing and activism at his father’s knee, and the duo are still today among the most prolific proponents of shareholder proposals at annual meetings. William Steiner, now 92, and his son have sponsored 230 proposals since 2007, according to a GMI Ratings database of the Russell 3000 companies.

“We are doing this as a public service,” the elder Mr Steiner says. “Communication between shareholders and top executives is very important to a company and to the nation. If the lines of communication had been open, you would not have people walking around downtown New York with placards hurling abuse at Wall Street professionals and shouting ‘down with companies’.”

The Steiners, along with their long-time collaborator John Chevedden – whose personal proposal count stands at 265 since 2007 – are in a line of dedicated and often eccentric activists who have taken to the floor of annual meetings, many drawing their inspiration from the brothers John and Lewis Gilbert.

Their five decades of haranguing chief executives began, according to the Los Angeles Times obituary of John Gilbert, in 1932, when Lewis attended a shareholder meeting and was refused permission to ask a question. The pair filed more than 2,000 proposals, attended up to 150 meetings a year and brought props with them.

After being forcibly ejected from a Chock Full o’ Nuts meeting, John Gilbert came back the next year wearing boxing gloves.

In their wake came a second generation of activists – or gadflies, as they were derisively known, for the nuisance they made of themselves – including Gerald Armstrong in Denver and the incomparable Evelyn Davis, whose approach to questioning chief executives was, by turns, to harangue and to flirt outrageously.

Ken Steiner, generation No 3, is sceptical that large institutional investors will pick up the mantle and put the gadflies out of business. “You have to rely on the concerned citizen,” he says.

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2017. You may share using our article tools. Please don't cut articles from FT.com and redistribute by email or post to the web.