Translators: Publishing’s unsung heroes at work

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

For John Cullen, his first few paragraphs are the most important and the most difficult. Just like the writers whose work he translates, he agonises over finding the right words. “I sit in my little office reading aloud to myself,” he says. “The first page has about 20 drafts. You have to see the spirit of the original author and to reproduce it. Particularly with a first-person narrative, it becomes very important to find the right voice. Once I hear that, or delude myself into thinking I have, I can go forward.”

Cullen translated into English from French the Algerian writer Kamel Daoud’s The Meursault Investigation , one of the African novels on the longlist of the FT/OppenheimerFunds Emerging Voices fiction award. His creative efforts illustrate a growing debate about the importance of translation and whether its practitioners deserve more recognition for bringing fiction from a broader range of cultures to a wider international readership.

One long-standing frustration by his peers is the limited demand for foreign writing in English. Christopher MacLehose, the veteran head of MacLehose Press, the publishing house that has given a platform to many writers from other languages, says the situation deteriorated in the latter third of the last century.

“When I first came into publishing, there was André Deutsch, Fredric Warburg, Ernest Hecht, Manya Harari, George Weidenfeld — a generation of multilingual people who came to England bringing the assumption that books that had to be translated were no different,” he says. “You simply published the best you could find and if you had to translate them, you just got on with it.”

By the 1970s, those visionaries had mostly retired, while the commercial pressures of large publishers had intensified. “In a big group, decisions are easily influenced by people in the accounts department who say translations are expensive.”

Alexandra Büchler, the founder of Literature Across Frontiers, a network designed to encourage cultural exchange, says the fact that the UK does not keep official statistics on translations is telling. Her research shows between 1990 and 2012, just 4 per cent of literary works published in the UK were translations, compared with 12 per cent in Germany, 16 per cent in France, 20 per cent in Italy and a third in Poland.

“The paradox is that Britain is a multicultural and multilingual society but it is also insular,” she says. “There is a view that there is excellent writing and variety in English and translation is expensive.”

Yet many claim the supply of, appetite for and value placed on translations is resurgent.

“Even in the past five years, there has been a noticeable difference,” says Daniel Hahn, who translates from Spanish, French and Portuguese. “One thing that helped was Scandinavian crime novels, which sold in colossal numbers. They demonstrated that translations are not off-putting. Foreign writers are much more visible today and there are lots of events on translation at book festivals now.”

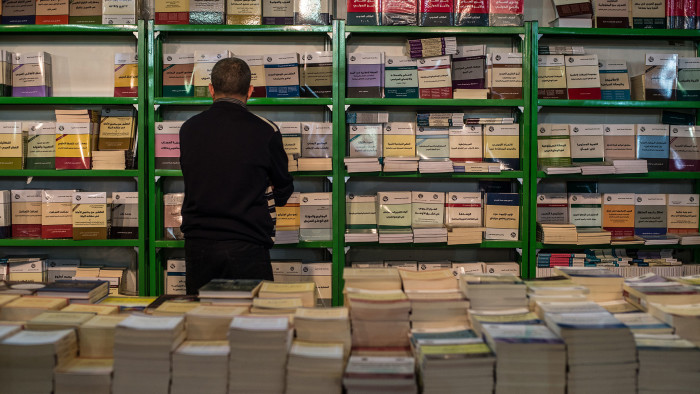

More widespread travel and Britain’s openness to global trends may have played a role. Büchler points to interest in regions in the headlines, such as with the Arabic-speaking world and specialist publishers such as Alma Books and And Other Stories have emerged.

A shift in the style of translation towards fluency and accessibility may also have helped. Specialists talk of a “domestication” of translations into an English that provides a smooth read rather than reproducing the quirks of the original. “There is a noticeable trend to try sounding like the living language as spoken,” says Cullen.

Grigory Chkhartishvili — who writes under the pen name Boris Akunin — author of the best-selling Fandorin historical detective series, stresses the importance of good translation. He says his first career, as a translator from Japanese into Russian, was partly inspired by reading different versions of Jerome K Jerome’s Three Men in a Boat. “The first time I read it as a kid, I couldn’t understand why it was supposed to be so funny. I didn’t even smile,” he recalls. “Then I read another version and I laughed like crazy.

“Good translation is all about the right words, the right paradoxes inside the phrase,” he says. “You are like a magician: you see something others don’t see. If you do everything right, it’s like replanting a flower. Fiction is not about ideas, thoughts and plot. It’s about the music, the style, humour. All sorts of literary, cultural and historical allusions get lost because of a different cultural background. A really excellent translator knows how to compensate. He has to produce the same effect on the reader as in the original language.”

Robin Moger, who translated Women of Karantina, by Egyptian writer Nael Eltoukhy, argues that there has been a particularly distinguishable shift in translations from Arabic, which was long dominated by a small group of university specialists.

“It was very academic, carried out by people on the mature side of middle age, who came from a place where literature is not read but consumed in academic circles as teaching aids,” he says. “I got a review from one who didn’t like the fact that the book reads fluently. But you are translating many other things apart from the work or the syntax. You are trying to relate enjoyment, tone and voice.”

Certainly Eltoukhy, who himself translates from Hebrew into Arabic, is delighted with Moger’s version. “It’s excellent. It keeps the random Egyptian spirit, the irrational way of thinking. He found an equivalent for every term including the jokes I thought would be impossible to translate.”

That raises a question: if translators are increasingly recognised for their contribution in the success of a novel, should they receive a greater proportion of credit? Some prizes, such as the Man Booker International Prize, explicitly judge translation skills and are splitting the reward between author and translator.

“I like the idea of an equal split,” says Hahn. “I can’t pretend I have put in as much time as the author, but my job is to do exactly the same as the original except for all the words. You have to create this entirely different language with the effect of the original.”

Own Words: Melanie Mauthner

Four years ago, Melanie Mauthner stumbled across the writings of Scholastique Mukasonga, (shortlisted for the Emerging Voices fiction award), in a library, where a collection of short stories in the original French was tucked away in the “community languages” section. Mauthner became an advocate for the author, seeking an independent British publisher willing to translate her work in English.

Her efforts were in vain, but Jill Schoolman, head of Archipelago Books in New York, which specialises in foreign fiction, independently acquired Mukasonga’s Our Lady of the Nile after discussions with Gallimard, the original French publisher. Mauthner was picked to prepare the English translation, which came out two years later.

“I have always read a lot translated from other languages,” says Mauthner, who studied French and Spanish at university and became a sociology lecturer before turning to translation. “People don’t realise that apart from grappling with the grammar, you are stepping into a whole different culture. The reader shouldn’t feel it’s a translation, just that they are being taken somewhere else.”

She says her preparations include reading other writers she finds inspiring, including Hilary Mantel. “She is someone who transgresses a lot. That makes her an exciting writer and makes you think you could do this too.

“Often it’s not the original language that makes translation difficult, but trying to work out what it will sound like in English,” she says. “It’s primarily about music — trying to make the music of English echo the music of the original.”

Comments