Craft versus Kraft

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Andy Warhol knew what he was doing. In the early 1960s, when he was looking to create a stir in the world of modern art, he fixed on an image as familiar to his audience as the Pietà was to Michelangelo’s — the Campbell’s soup can. It was both a consumer good and an icon of the age. Red and white, like the wine and bread of the sacraments Warhol knew from church, it promised comfort for the user once its condensed contents were mixed with water, heated and served.

But Warhol’s old models are now facing misfortune. The signature offering of Campbell Soup Company of Camden, New Jersey, founded in 1869, is falling out of favour with consumers in the US. Campbell’s condensed soup is no longer the stuff of modern art; it is becoming a symbol of days gone by, when Americans could be counted on to stock their pantries with the processed food brands advertised relentlessly on the three big television networks.

Today, a revolution is under way in US supermarkets. A more health-conscious millennial generation is forsaking the convenience food of their baby-boomer parents for fresher, more natural fare and proteins of various sorts. Burgeoning immigrant populations are stoking demand for different types of provisions. Beleaguered consumers are buying lower-cost store brands at bare-bones retailers, or cooking less and eating out more so they can work longer hours.

The result is that even as the US economy has recovered, some of the country’s best-known food companies — and some of their most enduring brands — have been suffering. Sales of Campbell’s condensed soup slipped 3 per cent year on year during its last six months of reported results. During the most recent quarter, North American revenues for Kellogg’s cereals and other morning foods fell 7.7 per cent, while Kraft Foods, the North American grocery business of the old consumer giant, reported a 6.6 per cent sales decline for meals and desserts, including its macaroni and cheese in a box.

So tumultuous are the culinary times that some of history’s most successful marketing organisations are admitting that they have lost touch with the people who buy their products. John Cahill, chairman and chief executive of Kraft, might as well have been speaking for the industry when he issued an extraordinary mea culpa this year as he cleaned his corporate house, saying goodbye to senior executives including his chief financial officer and adding a new “vice-president of growth initiatives”.

“It’s clear that our world has changed and our consumers have changed,” Mr Cahill said. “But our company has not changed enough.”

As is often the case with revolutions, this one has been a long time coming. As Michael Moss detailed in his 2013 book, Salt Sugar Fat: How the Food Giants Hooked Us, such companies prospered for decades by pursuing an ill-fated holy grail — finding the precise amounts of such ingredients that would produce maximum pleasure for the consumer. For sugar, it was even known as the “bliss point”. This effort helped food makers increase sales, but it made their customers more prone to obesity, heart disease and other maladies.

Americans have hardly kicked their addictions to salt, sugar or fat, but the experience of the big food companies shows they are trying, with younger people taking the lead. The millennial generation is shaking up the food industry, demanding products that are low in salt, sugar or fat, rich in protein or antioxidants, or free of artificial flavours, synthetic colouring and preservatives, genetically modified organisms, gluten or other ingredients that have fallen out of favour. They want to know how their food is being made — and who is making it. Craft is challenging Kraft.

“They are not going to eat what their parents ate,” says Jared Koerten, a senior food analyst at the Euromonitor market research firm in Chicago. “They are looking for something different — something ‘craft’. There is a general disinterest in brands.”

As the millennials have gravitated to quinoa, kale and Greek yoghurt, tens of millions of immigrants and their descendants have been turning a cold shoulder to the big brands by buying their traditional foods from providers who speak their language — either literally or gastronomically. Goya of New Jersey, the biggest Hispanic-owned food maker in the US, saw its sales jump 9 per cent last year, Euromonitor says, and is opening new facilities across the US, including one in Houston capable of producing 1,000 cans of beans a minute. Hispanic grocery chains such as California’s Mi Pueblo Food Centers and Sedano’s Supermarkets of Florida are growing apace.

MarketingSatisfying a customer craving for authenticity

In this time of Twitter and stories told in no more than 140 characters, there is something curious about the marketing materials of Annie’s Homegrown, an organic food maker based in Berkeley, California. They go on and on. They tell the story of the actual Annie — Annie Withey, who co-founded the company in 1989 “with the goal of making a healthy and delicious macaroni and cheese for families”. They show Ms Withey’s farm and discuss her pet rabbit Bernie. They feature annual sustainability reports attesting to Annie’s commitment to doing business “differently and with a purpose”.

Continue reading

John Stanton, a professor of food marketing at Saint Joseph’s University in Philadelphia, says the big food companies could be doing more to appeal to Hispanic consumers — by using Spanish in labels, for instance. “The demographics . . . are slipping away from them,” he says. “I don’t think they have kept up with the Hispanic population.”

The looming danger for blander US brands is that some of today’s “ethnic” foods will become tomorrow’s American foods, in the way of pizza and bagels. Already, spicy condiments favoured by Hispanic and Asian consumers — such as Sriracha hot chilli sauce, a favourite of US “foodies” — are giving tomato ketchup a run for its money. In 2000, Americans bought $696m worth of ketchup and $229m of chilli and spicy pepper sauces, according to Euromonitor, which adjusted its numbers for inflation. By 2014, the figures were $811m for ketchup and $608m for its hotter competitors.

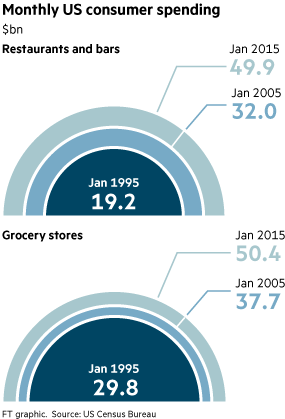

Compounding the problems of the big food companies is that some of their best-known brands may not be convenient enough for today’s consumers. Mixing condensed soup with water, or pouring milk into a bowl of cold cereal, very possibly takes too much time for workers holding down two jobs, or eating with one hand while holding an iPhone in the other. Americans now spend nearly as much money in restaurants and bars as they do in grocery stores, according to US Census figures, a development that speaks, at least in part, to the time pressures of the 21st century.

Lagging wages for lower-income Americans represent yet another challenge. Lower-cost store brands, also known as private-label brands, gained market share during the recession, and analysts suspect they could make further inroads. Aldi, a low-cost German grocer that mainly sells its own brands, announced plans last year to add 650 more US stores, including its first in southern California, to bring its total to about 2,000. “They have been absolutely exploding on the US scene,” says Euromonitor’s Mr Koerten. “They really appeal to consumers on a budget.”

The big food companies are responding. Campbell’s last month launched a line of premium ready-to-eat organic soups sold in green and white cartons. Kraft created P3 — short for portable protein pack, combining its Oscar Meyer meat with Kraft Natural cheese and Planters nuts. General Mills paid $820m for Annie’s Homegrown, an organic food maker that has been wooing “mac and cheese” lovers with such offerings as its Organic Peace Pasta and Parmesan — pasta shaped into peace signs and sold in a “fun tie-dyed box”.

But executives and analysts caution that the industry leaders have surprisingly little room for manoeuvre when it comes to defending some of their better-known brands. The underlying problem is ironic: these products still typically command fat profit margins. The ingredients — especially sugar and salt — are cheap and the consumer does much of the work for the manufacturer. Adding water to condensed soup, for example, means it can be shipped in a smaller container, reducing costs. Sourcing cold cereal from the same box saves money that would otherwise be spent on packaging the food into single servings.

Manufacturers could have invested in more advertising or better ingredients as sales of such products declined. But to please Wall Street, the big food makers have been tempted instead to cut costs, thereby maintaining profit margins in the face of eroding demand, the executives and analysts say. The question now is whether it is too late for the big companies to reverse the trend.

“The companies are cutting back on marketing, cutting back on research, cutting back on things that help them better understand the consumers and putting more emphasis on trade promotions, cutting price, giving deals to researchers, getting it on the shelf,” says Mr Stanton. “It really started falling apart in the late 1980s and 1990s — with more of the influence of the CFO in the company. I am very aware that business has to be financially sound. But when all you are looking at is the quarterly returns it encourages everybody to trade off current sales for future sales.”

The maddening trend for big food companies today is that they are often suffering death by a thousand cuts, steadily losing ground to lots of Lilliputian companies. Campbell’s overall share of the US soup market fell from 54.1 per cent in 2006 to 44.8 per cent last year, according to Euromonitor. By contrast, Pacific Foods of Oregon, which says it is “using simple ingredients, farming sustainably and acting kinder towards people, animals and the world around us”, saw its market share rise from 0.7 to 1.8 per cent.

“The problem is the landscape is changing to natural, organic, protein and non-processed foods,” says Brian Yarbrough, consumer research analyst at Edward Jones, a brokerage that advises nearly 7m investors. “The hard part is that all these companies that are winning in this game are so small.”

Indeed, one of the problems facing food makers is that today’s artists are probably more likely to make their own soup than depict it on canvas. In hipster areas of Brooklyn, New York, today’s closest equivalent to Warhol’s Manhattan demimonde, there is a flourishing soup culture. For $16 per quart (one litre), including a $2 deposit for the glass mason jar, the Brooklyn Soup Club promises to deliver such fare as roasted cauliflower soup with chimichurri, described as “creamy cauliflower puréed with onions, leeks, garlic and a light chicken stock, garnished with chimichurri, a mildly spicy condiment of green chillies, garlic, cilantro and mint, finished with a splash of cream, and touch of Parmigiano Reggiano”.

It’s a new age, with consumers who are far more demanding than those of previous generations. Campbell’s sold a lot of red-and-white soup cans by promising — in countless radio and television advertisements — that its products were “mmm, mmm good”. But providing such simple pleasures may no longer be enough.

Comments